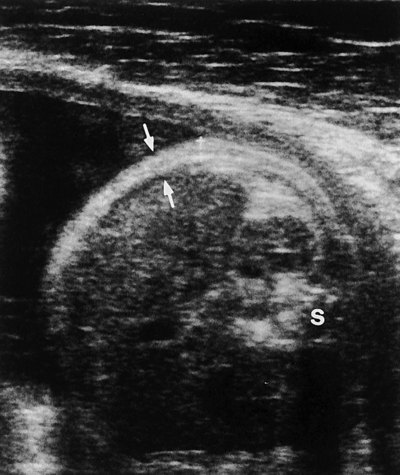

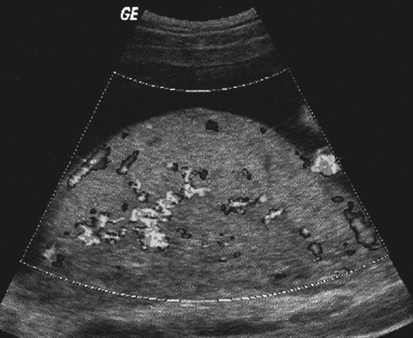

• Define terms associated with excessive fetal growth. • Differentiate between large for gestational age and macrosomia. • Identify the common causes of large-for-gestational-age pregnancies. • Describe the sonographic appearance of macrosomia. • List risk factors associated with macrosomia. • Describe the management of and interventions for suspected macrosomia. • Assess the relative size and age of multiple fetal parameters. Excessive fetal growth is typically divided into two categories with fetal weight in the determination. Large for gestational age (LGA) is a term suggested when the estimated fetal weight is greater than the 90th percentile for gestational age. Chapter 20 discusses the term small for gestational age, which is suggested when the estimated fetal weight is less than the 10th percentile for gestational age. Macrosomia is determined when the estimated fetal weight is greater than or equal to 4500 g. Appropriate fetal growth is clinically significant and a direct indicator of fetal well-being. Identification of fetuses that are not growing appropriately is important because as fetal growth discrepancy becomes progressively greater, whether from macrosomia or growth restriction, the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality is significantly increased. The major risk factor for macrosomia is gestational diabetes, which accounts for 40% of all cases. The prevalence rate of macrosomia is 25% to 42% among diabetic mothers versus 8% to 10% among nondiabetic mothers. Despite the higher frequency in diabetic mothers, nondiabetic mothers account for 60% of macrosomic cases because of their majority compared with the smaller number of diabetic mothers. Macrosomia is associated with enlargement of the placenta (Fig. 19-1; see Color Plate 17). A placental thickness obtained at a right angle to its long axis that measures greater than 3 cm before 20 weeks’ gestation or greater than 5 cm before 40 weeks’ gestation is considered abnormal. Time of delivery is an important factor to consider. One study showed an increased incidence of macrosomia from 1.7% at 36 weeks’ gestation to 21% at 42 weeks’ gestation. Chronic and progressing macrosomia is in direct proportion to an elevated risk of associated conditions, and women who have previously delivered a macrosomic infant are at an increased risk in future pregnancies. Primary perinatal complications include shoulder dystocia, soft tissue trauma, humeral and clavicular fractures, brachial plexus injury, facial palsies, meconium aspiration, prolonged labor, and asphyxial injuries. Shoulder dystocia (Fig. 19-2) occurs when the arm of the fetus prevents or complicates delivery and may result in serious traumatic injury. Because many of these injuries are unpredictable events, available evidence suggests that planned interventions on the basis of estimates of fetal weight may not significantly reduce the incidence of shoulder dystocia and the adverse outcomes attributable to fetal macrosomia. However, because evidence strongly suggests an increased risk of prenatal complications for pregnancies with fetuses weighing greater than 4500 g, the option for cesarean delivery should be considered with fetal macrosomia in diabetic patients with small pelvic structures and in any pregnancy where macrosomia is a concern. Hydrops fetalis is also associated with macrosomia and may manifest sonographically with one or more of the following: increased placental thickness, increased thickness of scalp or body wall greater than 5 mm (Figs. 19-3 and 19-4), hepatosplenomegaly, pleural and pericardial effusions, ascites, and structural fetal anomalies.

Size Greater than Dates

Excessive Fetal Growth

Estimation of Fetal Weight

Macrosomia

Risk Factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Size Greater than Dates