Fig. 15.1

(a–d) Coronal T2-weighted images of an 18-year-old baseball pitcher with 8 months of shoulder pain. A superior labral tear was identified, which is also clarified in the axial images of Fig. 15.2a–c. No rotator cuff or articular cartilage pathology was noted

Fig. 15.2

(a–c) Axial T1-weighted images of the 18-year-old baseball pitcher discussed in Fig. 15.1a–d. The superior labral tear extends from the posterior labrum at the level of the equator to near the level of the equator in the anterosuperior labrum. A paralabral cyst was noted along the posterosuperior labrum. The biceps tendon is intact without subluxation or change in signal

A labral tear extending from the posterior labrum at the level of the equator, through the superior labrum and into the anterosuperior labrum to the near level of the equator is demonstrated in both Figs. 15.1a–d and 15.2a–c. Mild signal heterogeneity and globular morphology of the anteroinferior labrum were noted, particularly in the axial images, without a discrete tear noted. A multilobulated paralabral cyst measuring 4 × 13 mm along the posterosuperior labrum was also demonstrated. The biceps tendon, visualized best in Fig. 15.2a–c, was intact without subluxation or increased signal. No rotator cuff or articular cartilage pathology was noted. Incidental note was made of moderate AC joint degeneration with intraosseous edema within the distal clavicle and acromion without significant mass effect upon the underlying supraspinatus.

Given the identified SLAP tear on MRI consistent with the patient’s clinical examination, risks and benefits of operative intervention were discussed with the patient, as he had failed extensive nonsurgical management. He elected to proceed with diagnostic arthroscopy and likely SLAP repair, given his age and activity level and desire to return to collegiate baseball.

Arthroscopy

The patient was taken to the operating room and placed in the beach chair position. A standard diagnostic arthroscopy of the right shoulder was completed. A type II SLAP tear was noted as demonstrated in Fig. 15.3a, b, both by probing and by an arthroscopic “peel-back” maneuver. The biceps tendon was intact. The anteroinferior labrum was also found to be intact. This correlated well with the findings on MRI: an isolated SLAP tear.

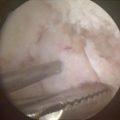

Fig. 15.3

(a, b) Arthroscopic images in the beach chair position demonstrating a type II SLAP tear, confirmed with an arthroscopic “peel” back maneuver. The biceps tendon was intact

Given the absence of biceps pathology or subluxation or significant degeneration of the superior labrum, the decision was made to proceed with arthroscopic SLAP repair in this young, athletic patient. The joint was insufflated, and a high rotator interval portal was established anteriorly for working purposes. Inside the joint, the detached tear of the superior labrum that involved a segment from approximately the 1 o’clock position anteriorly to approximately the 9 o’clock position posteriorly was easily mobilized with a probe. Additionally, with an arthroscopic peel-back maneuver, the patient was found to have mobility of the labrum off the glenoid surface superiorly in an abnormal fashion.

The superior and posterior aspects of the glenoid neck were debrided with a 4.2 mm shaver to bleeding subchondral bone. Two anchors were placed, one just posterior to the biceps anchor and one down at the 3 o’clock position. Sutures were then shuttled in a simple configuration and tied utilizing an arthroscopic knot tying technique (Fig. 15.4a–d). After repair, the superior labrum was probed and found to be stable with normalization of labral position with arthroscopic “peel-back” testing.

Fig. 15.4

(a–d) Arthroscopic images in the beach chair position demonstrating arthroscopic SLAP repair. The superior and posterior aspects of the glenoid neck were debrided with a 4.2 mm shaver to bleeding subchondral bone. Two anchors were placed, one just posterior to the biceps anchor and one down at the 3 o’clock position. Sutures were then shuttled in a simple configuration and tied utilizing an arthroscopic knot tying technique

The patient was placed in a shoulder immobilizer sling for 4 weeks postoperatively. Passive and active assisted shoulder range of motion was emphasized during the first phase of postoperative rehab (weeks 0–6), followed by active range of motion, terminal capsular mobilization, and strengthening beginning at week 6 and terminating at around 3.5 months postoperatively. The patient initiated a phased throwing program at 14 weeks postoperatively and was allowed to return to athletics and overhead sports at approximately 6 months postoperatively.

Discussion

The clinical presentation of a SLAP tear in an overhead athlete can be nonspecific, with the most common presenting complaints being pain with throwing and loss of velocity or accuracy as was noted in this patient. Exam findings including anterior or posterior joint line tenderness, the O’Brien’s active compression test, and biceps-specific tests such as Speed’s and Yergason’s tests can cumulatively be suggestive of a superior labral lesion. Imaging, consisting of an MRI with intra-articular gadolinium, can help with confirming a type II SLAP lesion. Arthroscopic SLAP repair most commonly yields successful outcomes, especially in the setting of a young patient, a traumatic onset of symptoms, and absent concomitant pathology. Outcomes in patients over the age of 35 or in throwing athletes can be less predictable, and thus patients in these groups should be counseled.

Case 2: Long Head Biceps Tendon Tear

History/Exam

A 39-year-old male presented to sports medicine clinic with a chief complaint of right shoulder pain, which was chronic in nature but worsening over the past 2 years prior to presentation. He reported the onset of symptoms when he was in college. He endorsed a distant history of two shoulder subluxations during sporting events but denied ever having a full dislocation. He noted significant exacerbation of his symptoms with overhead movements. He was able to play golf without symptoms, but his shoulder pain prohibited any overhead sports, such as tennis. He denied any recent subluxation events or feelings of instability.

On physical examination, he was found to have a positive O’Brien’s sign. His Speed’s test was positive as was his Yergason’s. He had mild tenderness over his bicipital groove. He had some very subtle apprehension. His strength and range of motion were normal, and he was otherwise neurovascularly intact and without symptoms in his contralateral shoulder. His long-standing symptoms and recent progressive deterioration warranted additional investigation with imaging.

Imaging

Initially, plain radiographs were obtained, which were unremarkable. There was no evidence of arthritic changes or glenoid or humeral head bony changes indicative of bony insufficiency leading to instability. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast arthrography was obtained to further evaluate the patient’s labrum, biceps tendon, and rotator cuff, due to his worsening symptoms. A complete sequence of images was obtained, including oblique coronal fat-saturated T1 and T2 sequences, oblique sagittal T1 and fat-saturated T2, axial T1 and fat-saturated T2, and oblique axial T1 sequences. Coronal fat-saturated T1-weighted images are demonstrated in Fig. 15.5a–c, and axial T2-weighted images are demonstrated in Fig. 15.6a–c.

Fig. 15.5

(a–c) Coronal fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of a 39-year-old male with chronic right shoulder pain. The coronal images demonstrate tearing of the superior labrum with contrast undermining the labrum. A low-grade undersurface and bursal irregularity of the supraspinatus tendon is also noted

Fig. 15.6

(a–c) Axial T2-weighted images of the same patient allow further characterization of the superior labral tear. The tear extends anteriorly and posteriorly to the level of the equator. There is subluxation of the biceps tendon, as the groove appears empty on the more cephalad images. There is also longitudinal splitting of the biceps tendon

The coronal images (Fig. 15.5a–c) demonstrate tearing of the superior labrum with contrast undermining the labrum. The inferior labrum as demonstrated on coronal imaging appears intact. This superior labral tear is further characterized on the axial images (Fig. 15.6a–c). The tear extends anteriorly and posteriorly to the level of the equator, confirming the diagnosis of a SLAP tear. The long head biceps tendon is best evaluated on the axial imaging provided (Fig. 15.6a–c). There is longitudinal splitting of the biceps tendon within the bicipital groove. Furthermore, there is subluxation of the biceps tendon, as the groove appears empty as the axial images move cephalad (Fig. 15.6b, c). Incidental note was made of mild narrowing of the anterior aspect of the glenoid articular cartilage. A low-grade undersurface and bursal irregularity of the supraspinatus tendon were also noted, most obvious in the coronal imaging, without any high-grade partial or full-thickness tearing identified.

The patient’s history, physical exam, and MRI were consistent with a SLAP tear and concomitant long head biceps tendon partial tear with subluxation. His symptoms were present and worsening over a several year period and were recalcitrant to conservative measures. Surgical intervention was offered, with a plan to address his biceps pathology with biceps tenodesis and to evaluate the superior labrum following this for potential concomitant repair. His low-grade rotator cuff irregularities noted on MRI were not suspected to be of consequence, given his lack of related symptoms on exam.

Arthroscopy

The patient was taken to the operating room and placed in the beach chair position. Given his questionable history of instability, an examination under anesthesia was carried out prior to skin incision. The patient was noted to have a low-grade anterior and posterior load and shift with a grade one sulcus sign. Diagnostic arthroscopy was then carried out. Through a standard posterior portal, the glenohumeral joint was entered. An anterior portal was then immediately established. Intra-articularly, the joint was inspected thoroughly. The chondral surfaces were intact. The patient was found to have a labral tear extending from approximately the anterior aspect of the biceps anchor into the posterior aspect of the labrum down to approximately the 9 o’clock position, confirming the diagnosis from MRI (Fig. 15.7a–d). There was fraying of the labrum itself. There was damage to the biceps anchor encompassing at least 25 % of the thickness of the biceps tendon itself. A second but substantially higher-grade injury to a long head biceps tendon was encountered at the groove entrance (Fig. 15.7a, b). This was at least 80 % if not 90 % of the caliber of the biceps itself with only a few small fibers remaining intact. The biceps was probed and the extent of this damage was confirmed down into the intertubercular groove region, confirming the findings noted on MRI. The biceps was substantially damaged. The rotator cuff was visualized. The patient has a low-grade articular sided rotator cuff tear involving only the far anterior aspect supraspinatus, as was noted on the MRI. This was debrided and contoured to a stable edge. The remainder of the labrum was intact. The subscapularis was also intact.