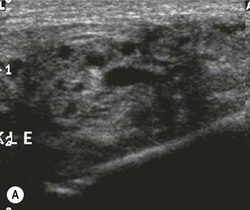

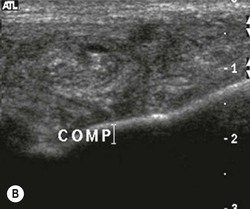

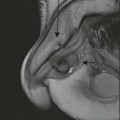

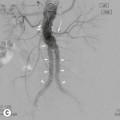

Paul O’Donnell Soft tissue masses are frequently referred for imaging assessment. The exact prevalence and the ratio of benign to malignant are impossible to estimate because: • If medical attention is sought, indolent masses may not be biopsied or excised. • Benign (and some malignant) masses are occasionally excised without imaging. Soft tissue tumours may be benign, malignant or non-neoplastic and all may present in a similar manner. Benign and non-neoplastic masses are more common, with benign lesions frequently said to occur approximately one hundred times more commonly than malignant.1 Referrals to hospital will be biased towards clinically suspicious masses and data from tumour centres give a distorted picture. In a study of 358 soft tissue masses referred from primary and secondary care, 95% of cases were benign.2 In a large study of consultation cases referred to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 68.5% of nearly 40,000 tumours were benign.3 The characterisation of soft tissue masses on imaging remains challenging and the histological diagnosis of sarcomas based on imaging, with a few exceptions, is frequently unsuccessful, necessitating biopsy. Benign and non-neoplastic masses may show typical imaging features, but biopsy is often still required to confirm the diagnosis. Radiographic assessment of a soft tissue tumour has a low diagnostic yield but may still be useful, either alone or as an adjunct to cross-sectional imaging. The utility of plain radiography has been assessed in 454 soft tissue masses referred to a tumour centre (care is needed in the extrapolation of these results from a referral population to soft tissue tumours in general).4 There was a positive finding in 62%. The most frequent finding was identification of a mass—most soft tissue tumours show similar density to muscle but a large mass may be seen, as may distortion (but preservation) of adjacent fat planes. In this study, a mass was seen in 31%. When seen on a radiograph, the lesion was more likely to be malignant although in part this depended on the location of the lesion, with visible tumours in the hands and feet more likely to be benign or non-neoplastic and tumours in the thigh, calf and arm more likely to be malignant. If the mass is large and contains fat in sufficient quantity, its density will be lower than that of adjacent soft tissues. Fat was seen in 7% of the masses: 50% were well-differentiated liposarcomas/atypical lipomatous tumours (see below), with benign fat-containing lesions including lipoma, haemangioma, hibernoma and lipoblastoma. Foreign bodies may be visualised on radiographs of a mass, as may a surrounding inflammatory reaction. Typically, glass and metal are visible but wood and plastic may not have sufficient density to be seen. Mineralisation was present in 17% of the soft tissue masses in the study. Phleboliths, due to dystrophic mineralisation of thrombus in abnormal vessels, may be seen and are the hallmark of venous malformations. The pattern of calcification may give an indication of the underlying histological nature of the mass. Chondral calcification (for example in soft tissue chondral tumours and synovial chondromatosis) may take the form of punctate foci in comma shapes, rings and arcs, suggesting cartilage. Ossification (for example in myositis ossificans), when mature, forms trabeculae and a cortex, with density at the periphery greater than at the centre. When immature, it forms a rather amorphous, mineralised mass. The pattern of calcification does not always help with the diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas, approximately 30% of which are mineralised, may display chondroid or either type of osteoid matrix.4 Abnormality of a bone due to an adjacent soft tissue mass may take several forms. The study by Gartner et al. showed cortical erosion, periosteal reaction, scalloping, intramedullary extension and pathological fracture affecting approximately 14% of subjects,4 and 39% of these were malignant. Changes were in general non-specific, with benign, non-neoplastic and malignant lesions capable of a wide range of interactions with the adjacent bone. Periosteal reaction was uncommon (4.4%), but 70% of cases showing it were non-malignant. Evaluation of the soft tissue mass with CT is useful in some cases but, as with radiographs, it is often not tissue specific, as many masses show similar attenuation to muscle. The radiographic features of a soft tissue mass are demonstrated at least as well using CT and it is more sensitive for the identification of small amounts of fat and calcium. As an adjunct to MRI and radiographs, CT is useful for showing the peripheral ossification in myositis ossificans, confirming what may be a difficult MRI diagnosis (Fig. 49-1). CT angiography (and specifically arteriography) is helpful for the preoperative assessment of tumours close to vessels. US has been shown to be a useful triage tool for masses referred from primary or secondary care.2 It can play an important role in confirming a mass is present and not due to a normal anatomical structure or variant (such as an accessory muscle). It can also differentiate solid from cystic lesions. However, once a solid mass has been confirmed, further characterisation with US may be limited, often requiring further assessment with MRI and possible biopsy. As an adjunct to MRI, US can further characterise masses that show fluid signal intensity (cysts and solid myxoid masses), assess vascularity and compressibility (typically of venous malformations (Fig. 49-2)) and allows valuable clinical correlation by the examining radiologist. Diagnostic features may be present in some lesions and these are more frequently benign or non-neoplastic. Examples include traumatic (muscle/tendon tear, haematoma), infective (abscess, pyomyositis), lipomatous (superficial and deep fatty masses—the latter usually need further assessment with MRI), vascular (thrombophlebitis, venous malformation, pseudoaneurysm) and neurogenic (nerve sheath tumours, nerve pseudotumours). In the differentiation of a malignant from a benign solid mass, the grey-scale appearances are usually non-specific. The assessment of tumour vascularity using colour/power and pulsed Doppler is possible with US and greater success has been claimed. Tumour neovascularity is an important feature of malignancy—tumour vessels are anatomically abnormal, lacking a muscular layer and showing irregular contour. This results in a heterogeneous network of abnormal vessels, often chaotically distributed within the tumour, with abnormal flow characteristics and morphology. A study of benign and malignant masses with high vascularity showed that the pattern of vessels within a mass was of limited value in the distinction of benign and malignant, but that in the presence of an organised pattern, a benign diagnosis was more likely.5 An organised vascular pattern has been shown in 77% of benign and a disorganised pattern in 80% of malignant soft tissue tumours.6 The atypical morphology of vessels in malignant masses may result in vessel trifurcations (rather than bifurcations), stenoses, occlusions and an anarchic rather than an hierarchical branching pattern.7 Identification of any two of these ‘major’ criteria enabled malignant and benign masses to be distinguished. MRI is the technique of choice for local staging of a soft tissue mass, especially if it is in a deep location where US may be less able to assess tumour extent and relations. It is sensitive, can be tissue-specific and allows assessment of most masses, no matter where they are located. Despite this, MRI is often not sufficiently tissue specific to allow confident identification of some deep, solid masses; distinction of myxoid from cystic masses can be difficult without contrast medium and small calcific foci may not be seen. MRI also overlaps with radiography in its ability to identify fat, a foreign body and bone involvement in a soft tissue mass: differentiation of mineralisation and gas may require radiographs or CT, as both show hypointensity on T2-weighted (T2W) images and also on other fluid-sensitive sequences (see below). Most tumours, and certainly most soft tissue sarcomas, are isointense to muscle on T1-weighted (T1W) images, of intermediate signal intensity on T2 images (similar to fat) and hyperintense on inversion recovery (STIR) or T2W images with fat saturation. As with US, specific diagnoses can sometimes be suggested based on the MRI appearances, more often with benign and non-neoplastic lesions, which may exhibit specific signal characteristics. Examples of MRI signal that allow characterisation and occasionally an MRI diagnosis (in combination with lesion morphology) include T1 hyperintensity, T2 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity (fluid signal). Hyperintensity on T1W imaging is commonly due to fat or subacute haemorrhage (methaemoglobin), but may also be due to melanin. Hypointensity on T2W imaging may be due to calcification, fibrous tissue, chronic haemorrhage (haemosiderin), rapidly flowing blood (for example in an arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm) or gas. A radiograph is useful for excluding calcification as a cause. Hyperintensity on T2W imaging may be seen in cystic masses, abscesses, myxoid masses (which include intramuscular myxomas, sarcomas and some nerve sheath tumours) and low-flow vascular malformations. The presence of fluid–fluid levels is a non-specific sign in soft tissue masses: they are rare and equally common in benign and malignant lesions. The presence of haemorrhage is, however, useful—tumour necrosis is often seen in high-grade sarcomas; certain sarcomas (particularly synovial sarcoma) frequently show haemorrhagic foci (in synovial sarcomas up to 47%). Staging of soft tissue sarcomas is best undertaken with MRI. This requires documentation of the size and local extent of the tumour, including any extracompartmental spread and the relationship of the tumour to adjacent structures such as bones, joints and neurovascular bundles. Initial staging will also usually require a chest radiograph and CT to exclude pulmonary metastases.

Soft Tissue Tumours

Introduction

Imaging Characterisation of Soft Tissue Masses

Radiographs

Computed Tomography (CT)

Ultrasound (US)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours8

The most recent version (2002) classified the following types of soft tissue tumours

• Fibroblastic/myofibroblastic

• So-called fibrohistiocytic tumours

• Pericytic/perivascular tumours

into the categories benign, intermediate and malignant. Several changes were made in this updated classification, including the recognition of two distinct types of intermediate malignancy (‘locally aggressive’ and ‘rarely metastasising’) and the reclassification of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, previously considered the commonest type of soft tissue sarcoma, as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Many of the changes will be irrelevant to the imaging assessment of a soft tissue mass—the pathological diagnosis is being continually refined, particularly with the evolution of genetic techniques. It should be noted that peripheral nerve and skin tumours, both of which present as soft tissue masses, are considered in separate WHO classifications. Metastases to soft tissue and haematological malignancies, particularly lymphoma, may also present as a soft tissue mass.9 Imaging is useful in the diagnosis of some of these soft tissue lesions and will be discussed below.

Lipomatous (Adipocytic) Tumours

Lipomatous neoplasms are the most frequent mesenchymal tumours, with subcutaneous lipomas thought to represent up to 50% of all soft tissue tumours10 and liposarcoma representing the commonest soft tissue sarcoma.8

Lipoma

This is a benign adipocytic tumour and the commonest mesenchymal neoplasm in adults. Lipomas typically occur in adults in the fifth to seventh decades with no sex predilection. They are rare in children and may be multiple.8 Superficial (subcutaneous) tumours are common but lipomas may also occur in deep locations (intramuscular or intermuscular), or even adjacent to bone (parosteal), where they may stimulate a periosteal response. Subcutaneous lipomas are often diagnosed with great accuracy on clinical grounds alone, presenting as small (usually <5 cm), painless, firm, mobile masses.11 Deep lipomas are often larger, but again usually painless. They cannot be diagnosed clinically and imaging is needed to confirm the diagnosis in deeper lesions. Atypical clinical presentation includes pain due to nerve compression in restricted spaces such as the carpal, tarsal and cubital tunnels.

Lipomas can contain other non-lipomatous elements contributing to a heterogeneous imaging appearance, vessels (angiolipoma), muscle (myolipoma), cartilage (chondrolipoma), bone (osteolipoma—following trauma or ischaemia) or extensive myxoid change (myxolipoma). Fibrous tissue and foci of fat necrosis can also cause a heterogeneous appearance.

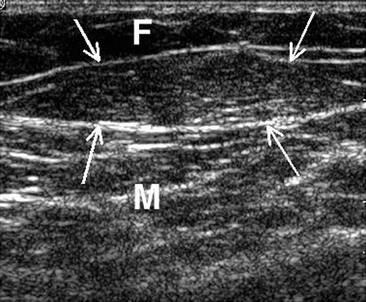

Ultrasound

Subcutaneous lipomas are usually elliptical masses, often well-defined, with their long axis orientated parallel to the skin surface (Fig. 49-4). Their reflectivity is variable, while subcutaneous fat is usually low in reflectivity (unless previously inflamed or traumatised); lipomas are relatively reflective, often showing septation orientated along the long axis of the lesion. One study showed 29% had lower reflectivity than surrounding tissues and the remainder was of similar, greater or mixed reflectivity.12 Light pressure with the ultrasound probe shows the lesions are compressible. They may appear encapsulated although many lipomas appear to blend with the surrounding tissues without evidence of a capsule.

Computed Tomography

This is rarely performed in the case of a subcutaneous lesion, but may show a mass of density similar to that of subcutaneous fat. Non-encapsulated lipomas may be occult. Deeper lesions are more likely to show heterogeneity (non-lipomatous elements, foci of mineralisation).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The mass is isointense to subcutaneous fat on T1- and T2W imaging, showing low signal intensity on STIR images and suppression of fat signal on T2W imaging with fat saturation. Fine septa (often immeasurable, typically less than 2 mm) are often seen, but the absence of thick or nodular septa is useful for differentiating a lipoma from a well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumour. Fine septa are also less likely to show gadolinium enhancement in benign lesions, which is also useful for differentiation.13 Focal areas of non-adipose tissue (including fibrosis and necrosis) are not infrequent in benign tumours (particularly deep lesions) and make the distinction from a well-differentiated liposarcoma impossible on imaging alone. Mineralisation (calcification and ossification) may also be seen in benign tumours.

Intramuscular lipomas can be diagnosed with a high degree of confidence; an infiltrative margin and intermingled muscle fibres within and at the periphery of the lesion are features that make it possible to differentiate from other lipomatous tumours14 (Fig. 49-5).

Although they may be seen in simple lipomas, the following MRI features are atypical and should suggest the possibility of a well-differentiated liposarcoma:

Other Benign Adipocytic Tumours

Lipoblastoma

Lipoblastoma is a tumour occurring in children—88% of patients are under 3 years old and the median age at onset is 1 year.15 They usually occur in the extremities and consist of both mature and immature adipocytes (lipoblasts).8 Lesions in younger patients contain prominent areas of myxoid tissue and MRI appearances may mimic a myxoid liposarcoma. However, they undergo a process of maturation, showing a tendency to develop into lipomas.16 Imaging reveals a heterogeneous fatty mass on US, CT and MRI, due to myxoid and cystic areas, but, as both lipoma and liposarcoma are rare in young children, the diagnosis can be suggested in the presence of a heterogeneous fat-containing mass in a patient of the correct age.

Hibernoma

Hibernoma is a rare benign tumour composed of brown fat most frequently occurring in the thigh. The tumour appears lipomatous, but usually shows subtly different signal characteristics from those of subcutaneous fat, with hypointensity on T1W imaging and failure to suppress fully on fat-saturated images. Serpentine vessels may be identified within the highly vascular mass, a rare finding in an atypical lipomatous tumour/well-differentiated liposarcoma.11

Atypical Lipomatous Tumour/Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma (ALT/WDL)

These lesions are synonymous and classified as intermediate (locally aggressive) malignancies. They account for 40–45% of all liposarcomas and are the commonest subtype of liposarcoma.8 ALT/WDL are well-differentiated tumours, often predominantly fatty, and show no capacity for metastasis unless dedifferentiation occurs (see below). Although ALT and WDL are identical morphologically and genetically, the term ALT is used for tumours in surgically accessible sites, such as the limbs and trunk, where complete excision is curative. WDL is usually used for tumours in inaccessible sites, such as the mediastinum and retroperitoneum, where complete excision may not be possible and the disease may eventually be fatal following uncontrolled recurrence.

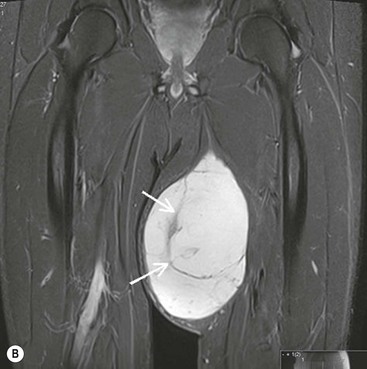

These tumours occur in middle age, most commonly in the sixth decade and there is no sex predilection. They arise in the deep soft tissues of the limbs, retroperitoneum, paratesticular area and mediastinum—rarely they occur subcutaneously.8 Imaging shows a deep lipomatous mass with varying degrees of heterogeneity. The following features favour a diagnosis of a malignant rather than a benign tumour: lesion size >10 cm, thick, nodular septa, presence of globular or nodular non-adipose areas and fat content less than 75%17 (Fig. 49-6). Incomplete fat suppression suggests a liposarcoma,18 while septal enhancement is more likely if the lesion is malignant and may be more important than the thickness of the septa.13,19 Although on imaging the differentiation of a lipoma in a deep location from ALT/WDL is unreliable, with considerable overlap in the appearances, it is largely irrelevant to initial management. Both are well-differentiated lipomatous neoplasms and would usually be treated by primary excision, with as wide a margin as possible, without prior biopsy.

Other Adipocytic Malignancies

The other major types of liposarcoma are dedifferentiated, myxoid and pleomorphic (pleomorphic liposarcoma is a very rare high-grade tumour). With higher grades of malignancy, fat becomes less conspicuous on MRI, such that there may be no suggestion of an adipocytic tumour in many liposarcomas.

Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma results from the transition of ALT/WDL to a non-lipogenic sarcoma of variable grade and may occur in the primary tumour (90%) or in a recurrent lesion. The risk of dedifferentiation is greatest in retroperitoneal tumours and occurs in up to 10% of ALT/WDL—this may be time dependent rather than location dependent. It is usually a high-grade tumour, with the dedifferentiated component seen as a discrete non-lipomatous tumour within the fatty mass, reflected in both the histological and radiological appearances (Fig. 49-7). Occasionally, there is a gradual transition from lipomatous to non-lipomatous sarcoma.

Myxoid Liposarcoma

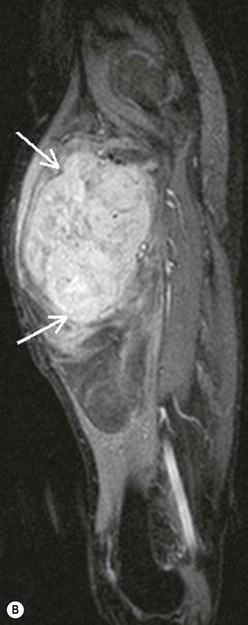

Myxoid liposarcoma is the second most common type of liposarcoma, accounting for approximately 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas. The tumour consists of a myxoid stroma containing primitive non-lipogenic mesenchymal cells and a variable number of lipoblasts. An imaging diagnosis based on its MRI appearances is frequently possible and dependent on identifying the myxoid component, which resembles fluid, along with a fatty component, usually in the form of thin T1 hyperintense septa (often subtle) (Fig. 49-8). In the most recent WHO classification of soft tissue tumours, round cell liposarcoma, previously considered separately as the cellular, high-grade variant of myxoid liposarcoma, was reclassified as a synonymous lesion.

Fibroblastic/Myofibroblastic Tumours

Nodular Fasciitis (NF)

This is a fibrous proliferation that forms a rapidly growing mass, usually in the subcutaneous tissues, but is also found in intramuscular and intermuscular (fascial) sites. Owing to its rapid growth, cellular histology and frequent (although not atypical8) mitoses, inappropriately aggressive surgery may be performed. It is said to be the commonest lesion of fibrous origin,20 occurring in all age groups, but most commonly affecting young adults,8 with no sex predilection. The most frequent sites of involvement are the upper limb (48%) and trunk (20%),20 although any site is possible. Imaging shows a mass, which is usually small (< 5 cm in maximum dimension, mean 2.2 cm diameter in one series20), and often poorly defined, whose MRI characteristics reflect the histology: the nodule undergoes a process of maturation, with early, cellular lesions containing myxoid tissue (near-fluid signal intensities, but slight T1 hyperintensity compared with muscle), later becoming fibrotic (hypointense on all sequences, including T1). NF has been treated, following confirmatory biopsy, with intralesional steroid injection and surgery, with few recurrences following excision.21

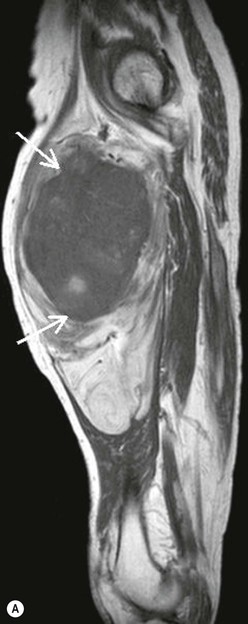

Elastofibroma (EF)

This is a tumour-like lesion (fibroelastic pseudotumour) occurring almost exclusively in elderly patients, consisting of mature adipose tissue entrapped within a fibrous mass, typically found adjacent to the inferior angle of the scapula. When typical in location and appearance on MRI, no biopsy is required and marginal resection suffices. The lesion is common and often bilateral. Over 50% of cases are said to be asymptomatic22 and it is a frequent postmortem finding.23 There is a reported prevalence of 2% in subjects >60 years undergoing chest CT for lung disease.24 EF is thought to arise as a result of friction between the scapula and chest wall, possibly due to manual labour, resulting in collagen degeneration, but familial cases do exist.

Over 99% occur at the typical chest wall location, but other sites, including visceral sites, have been described.8 US shows non-specific appearances but the mass can be revealed, sometimes fairly dramatically, with shoulder adduction. The appearances on CT and MRI reflect its fibroadipose contents. EF contains alternating striations of fat and fibrous tissue and is typically elliptical, located deep to serratus anterior (Fig. 49-9). The striations parallel the chest wall. Bilateral, symmetrical masses may cause confusion, as the mass may superficially resemble muscle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree