Soft Tissues Injury of the Neck

Oleg M. Teytelboym

Kevin A. Smith

Penetrating and blunt (nonpenetrating) neck trauma can cause injury to any of the vital structures (in order of frequency): (1) great vessels, (2) larynx and trachea, (3) pharynx and esophagus, (4) spinal cord and brachial plexus, and (5) thoracic duct. If physical examination reveals clear signs of injury to one of these structures, immediate surgical exploration and repair is usually indicated. Patients who are asymptomatic can often be evaluated with noninvasive tests.

Lateral neck is divided by the sternocleidomastoid muscle into an anterior and posterior triangle.

Anterior triangle is the most common site of penetrating injury of the neck. Penetrating wounds into the anterior triangle can injure the internal and external carotid arteries, the jugular vein, and the vagus nerve.

Wounds in the posterior triangle are often less associated with serious visceral and vascular injuries, unless they are located inferiorly, where injuries can involve the internal jugular vein, phrenic nerve, brachial plexus, and subclavian arteries and veins.

Anterior neck describes injuries near the anterior midline, where the trachea and esophagus are most susceptible.

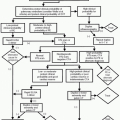

The neck can be divided into three zones on the basis of the site of injury. Zone of injury has significant implications for patient management.

Zone I. Below the sternal notch can be fatal due to injury of great vessels and esophagus. These injuries may be clinically silent requiring thorough evaluation of every patient regardless of symptoms.

Zone II. Above the sternal notch and below the angle of the mandible. Zone II is the most frequent site of injury. Older surgical literature suggested surgical evaluation of any injury that penetrated the platysma. Modern protocols increasingly rely on noninvasive testing to avoid surgery in asymptomatic patients.

Zone III. Above the angle of the mandible. Penetrating injuries can result in injury of major blood vessels and cranial nerves. Up to 25% of patients with significant arterial trauma are asymptomatic at presentation. Routine surgical exploration is not feasible due to the complex anatomy in this zone.

Symptoms and Signs.

Most laryngotracheal injuries cause acute symptoms and physical findings, whereas vascular and pharyngoesophageal injuries are more often occult on initial presentation. Penetrating projectiles are associated with a higher incidence of severe injury than stab wounds.

Vascular injury, pulsatile arterial bleeding, hematoma, diminished distal arterial pulsation, bruit, unexplained shock, and neurologic changes are indicative of an ischemic or embolic event. Brain infarction and hemorrhage are major sequelae and may occur acutely or remotely after the injury.

Aerodigestive injury, stridor, dysphonia, aphonia, hemoptysis, and subcutaneous emphysema are among the most common findings in airway (laryngotracheal) injury. Hematemesis, dysphagia, odynophagia (pain on swallowing), subcutaneous emphysema, hydropneumothorax, and widened mediastinum suggest an injury to the esophagus or pharynx.

Penetrating Injury Management Protocol

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree