Soft Tissues of the Neck

For descriptive purposes on MR and CT, particularly on axial imaging, the neck is divided into spaces. The masticator space contains the muscles of mastication (lateral and medial pterygoid, temporalis, and masseter muscles—all innervated by CN V3), the ramus and posterior body of mandible, and the pterygoid venous plexus. Infection and tumor can spread from the masticator space to the PPS and skull base. The submandibular space is directly continuous with the sublingual space at the posterior free margin of the mylohyoid muscle. The CS extends from the skull base to the aortic arch and is enclosed by the carotid sheath. It contains the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein (with the right greater in size than the left in 80% of patients), cranial nerves IX to XII, and the sympathetic plexus. The PPS was previously described, and lies anteromedial to the CS. The prevertebral space is that between the prevertebral fascia and the vertebrae. The posterior cervical space lies posterolateral to the CS, deep to the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The retropharyngeal space (RPS) lies posterior to the pharynx and anterior to the prevertebral muscles extending from the skull base to the mediastinum. In addition to its main fat component, the suprahyoid RPS contains important medial and lateral RPS nodes.

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes lie throughout the soft tissues of the neck. A common radiologic classification of lymph nodes in the neck, which is used predominately for squamous cell carcinoma, defines seven levels. Level I is subdivided into Ia, the submental nodes, and Ib, the submandibular nodes. Level II encompasses the internal jugular chain of lymph nodes, and extends from the base of the skull to the hyoid bone. It is subdivided into level IIa, those anterior, lateral, or medial to the vein and those immediately posterior but inseparable from the internal jugular vein, and level IIb, those posterior to the vein but with a fat plane interposed. Level III is composed of the internal jugular chain of lymph nodes from the hyoid level to the cricoid, with level IV nodes being those from the cricoid to the clavicle. Level V nodes are those within the posterior cervical space (posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle), level VI nodes are anterior triangle nodes (anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle), and level VII are superior mediastinal nodes. Nodes of importance that are not contained in this nodal classification include the intraparotid nodes and the retropharyngeal nodes (not amenable to physical examination).

On CT, size is an important criterion for identification of abnormal lymph nodes. Nodes larger than 10 mm in the short axis are considered abnormal, with the exception of level I nodes and the jugulodigastric node, where 15 mm is used as the cutoff ( Fig. 2.102 ). By size criteria alone, up to 20% of lymph nodes are incorrectly classified (in regard to involvement by neoplastic disease). It should also be kept in mind that there are many benign causes of lymph node enlargement. These include infectious mononucleosis ( Fig. 2.103 ) and cat-scratch disease.

Size independent criteria include loss of the fatty hilum and necrosis (the latter reinforcing the importance of contrast enhancement, whether imaging with CT or MR). DWI has added a new dimension to MRI in the head and neck (with recent technologic advances making possible diagnostic quality DWI in this region), providing improved sensitivity and specificity, with increased utility for evaluation of treatment response and detection of local recurrence. Although restricted diffusion is a marker of lymph node involvement by neoplastic disease, experience in this area is still limited with evolution of standards and diagnostic criteria.

Congenital Anomalies

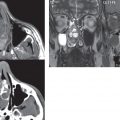

Congenital anomalies in the neck include branchial cleft anomalies, thyroglossal duct cysts, and lymphatic/venolymphatic malformations. The vast majority of branchial cleft cysts (95%) arise from the second branchial cleft. Only 5% are first branchial cleft cysts. Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are quite rare. Sinus tracts, communicating with the skin (or gut), occur but are rare. Most second branchial cleft cysts are located at the angle of the mandible ( Fig. 2.104 ). Most first branchial cleft cysts are either periauricular in location or close to the parotid ( Fig. 2.105 ). Clinically, branchial cleft cysts present classically in a child or young adult as a painless mass.

A thyroglossal duct cyst (TGDC) is the most common congenital neck lesion, and usually presents in children. During embryogenesis, the thyroid develops at the base of the tongue (foramen cecum), and subsequently descends (along the thyroglossal duct), looping behind the hyoid bone, to reach the thyroid bed. The duct then normally involutes. Migration of the thyroid can be arrested at any point—for example, a lingual thyroid being total failure of migration. Thyroid tissue may lie along any portion of the tract. A TGDC can be midline (suprahyoid) or paramedian (infrahyoid, typically lying deep to, or embedded within, the strap muscles) ( Fig. 2.106 ). Approximately 50% of cysts lie at the level of the hyoid, 25% in the suprahyoid neck and 25% infrahyoid in location.

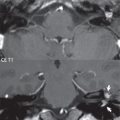

Seventy-five percent of lymphatic malformations occur in the neck, mainly in early childhood, presenting as a painless mass. Many of these lesions harbor components of venous malformations and are termed venolymphatic malformations. The imaging appearance is that of a nonenhancing cystic mass, typically multiloculated, with an imperceptible wall ( Fig. 2.107 ). Hemorrhage can occur within these malformations, and there can be fluid-fluid levels which are virtually pathognomonic. The most common location of these lesions is in the posterior cervical space.

Infantile hemangiomas are classified as benign vascular neoplasms (not a congenital anomaly); however, 90% involute over time without treatment. One-third are seen at birth, with the median age of presentation being 2 weeks. Visually they appear as cutaneous red, purple, or blue, plaque, or berry-like lesions. On MR, these demonstrate intense, uniform enhancement, with vascular flow voids common ( Fig. 2.108 ). Infantile hemangiomas are hyperintense on T2-weighted scans. Most occur in the head and neck region, often parotid or buccal in location. Enlarged feeding arteries can be visualized on contrast enhanced MR angiography. Twenty percent are multifocal ( Fig. 2.109 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree