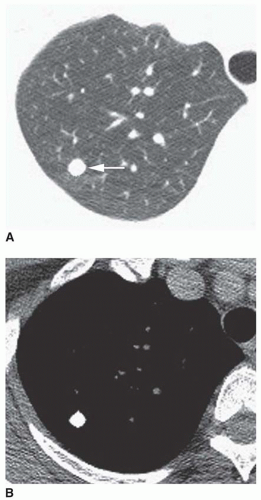

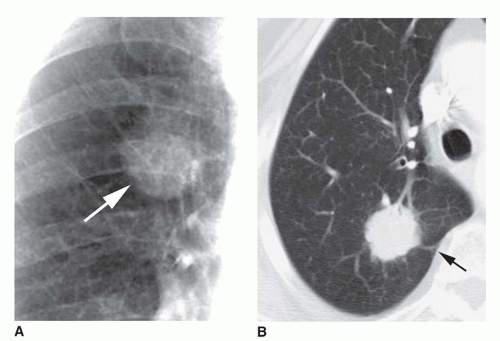

A lung nodule usually is examined using volumetric HRCT to determine its attenuation before contrast injection. Because of volume averaging, unless an SPN is grossly calcified, CT with thick collimation (5 mm) usually cannot be used to determine its attenuation accurately. Most cancers appear to be of soft tissue attenuation.

Calcification or High Attenuation

The presence of calcium in an SPN increases its chances of being benign (

Table 9-9). Diagnosing a small nodule as calcified on chest radiographs is somewhat subjective and subject to error. However, if a nodule a few millimeters in diameter is easily seen on radiographs, it probably is calcified.

CT is more sensitive and accurate in diagnosing calcification. Volumetric HRCT images usually should be obtained through a lung nodule to look for calcium. HRCT demonstrates calcification in about 25% of benign SPNs that do not appear calcified on plain radiographs.

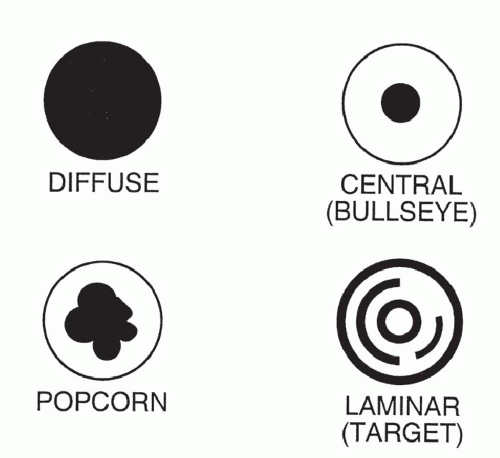

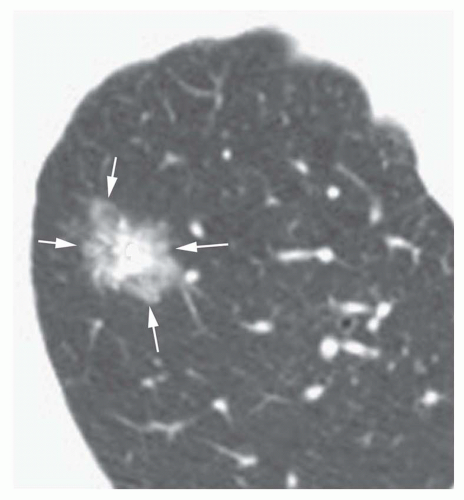

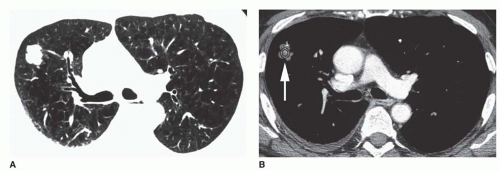

The pattern of calcification is important in determining its diagnostic significance. Generally, the following four patterns of calcification can be used to predict the presence of a benign lesion with sufficient accuracy to allow appropriate management (

Fig. 9-14):

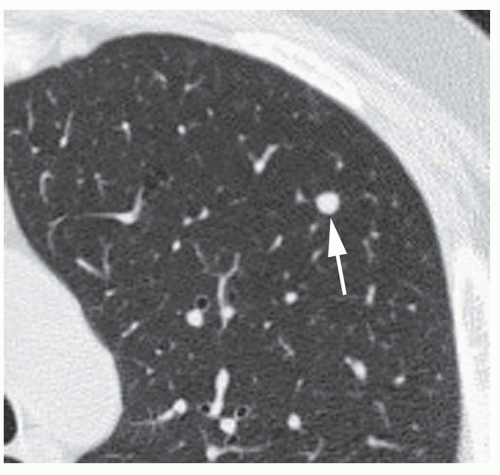

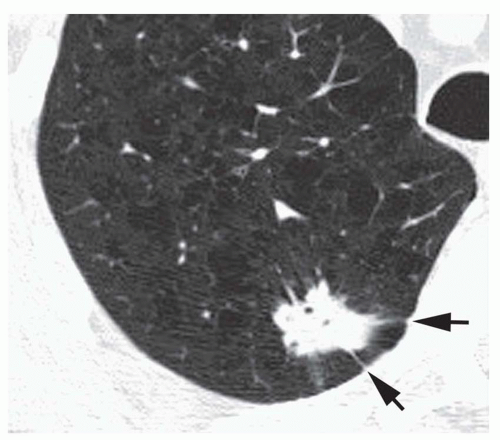

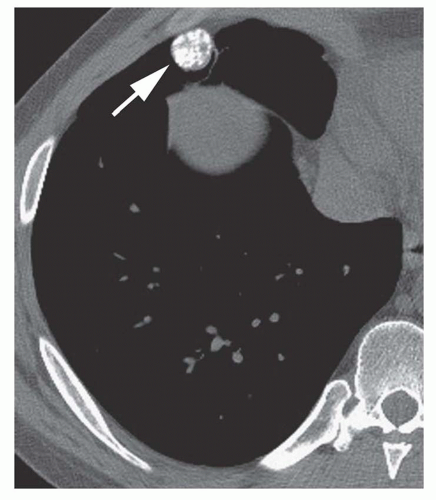

Dense central (bull’s-eye) calcification (

Fig. 9-16)

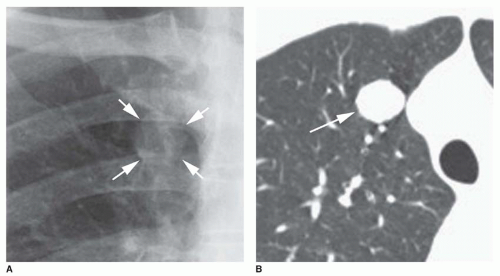

Concentric rings of calcium (“target” calcification;

Fig. 9-17)

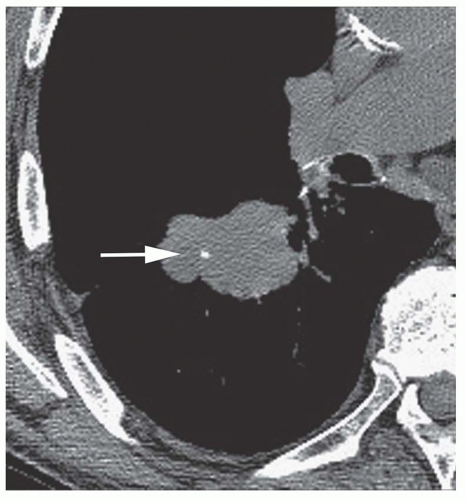

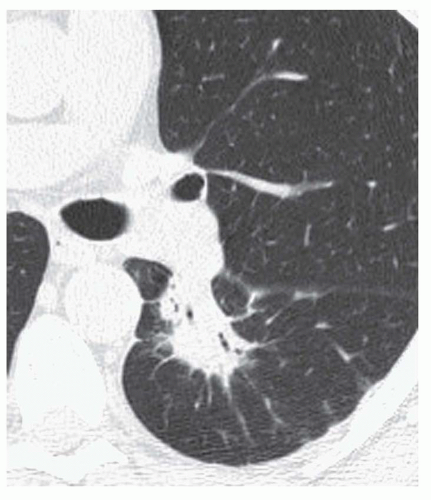

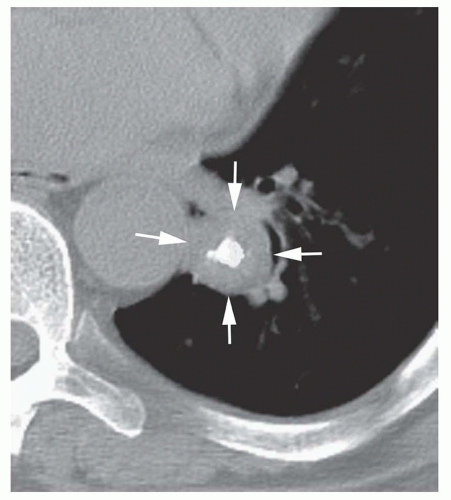

Conglomerate foci of calcification involving a large part of the nodule (“popcorn” calcification;

Fig. 9-18)

The first three of these patterns are most typical of granulomas; the last is more typical of hamartoma. Calcified lesions thought to be benign should be followed up radiographically in most cases unless the calcification is diffuse.

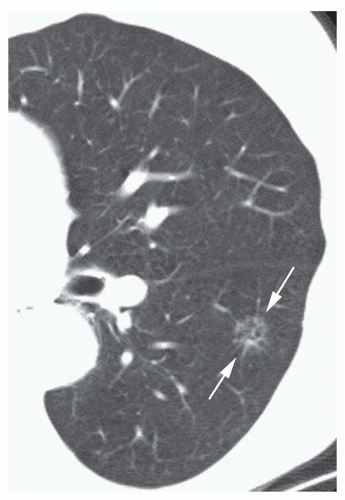

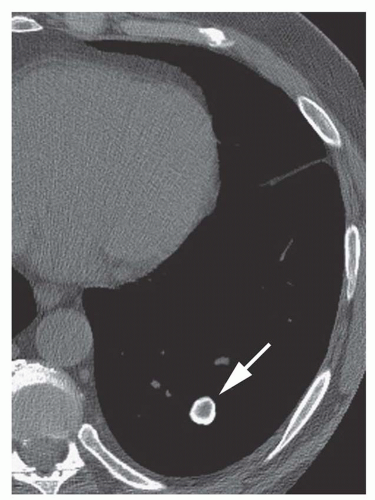

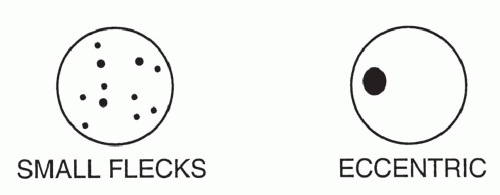

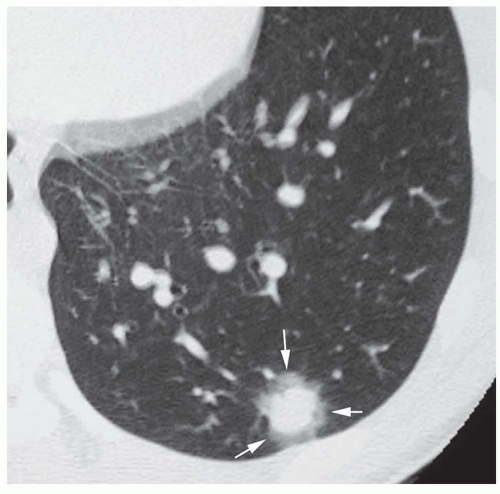

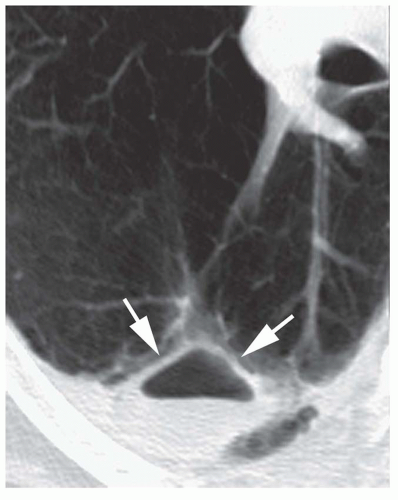

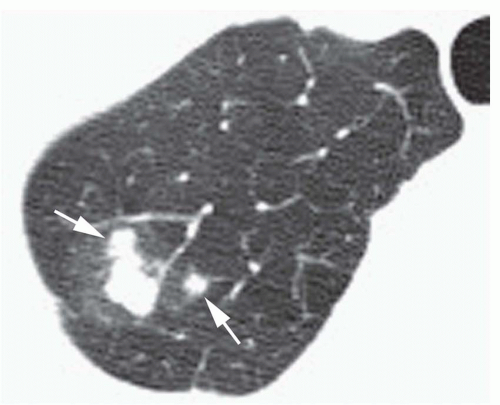

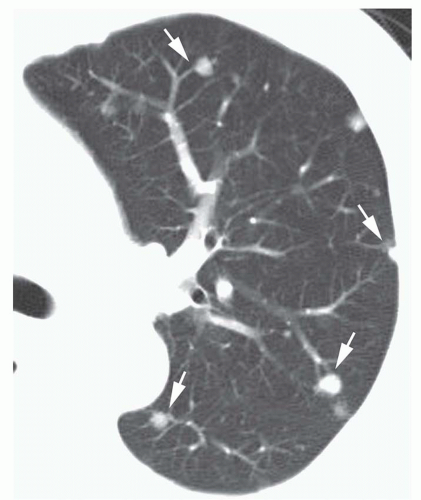

Stippled calcification or eccentric foci of calcification (

Figs. 9-19 and

9-20) may be seen in benign SPNs but are visible in as many as 10% to 15% of cancers; these patterns must be considered indeterminate (see

Fig. 9-19).

Calcium in a tumor may reflect dystrophic calcification (occurring in areas of tumor necrosis), engulfing of a preexisting granuloma, or calcification of the tumor itself (as in mucinous adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor, or osteogenic sarcoma). A “benign” pattern of calcification occasionally is seen in patients with neoplasm. Carcinoid tumor and mucinous adenocarcinoma can show dense central calcification. Metastases from osteogenic sarcoma or chondrosarcoma can show homogenous calcification, but a history of the primary tumor allows a correct diagnosis.

Because of the high likelihood of cancer in patients with spiculated nodules or nodules exceeding 2 cm in diameter, it is inadvisable to call such a nodule benign on the basis of visible calcification, unless the calcification is diffuse and dense. A small central calcification is insufficient for determining whether such a nodule is benign.

Usually, a visible inspection of HRCT scans is sufficient for diagnosing calcification. However, the measurement of

CT numbers can allow the detection of calcification, which is not clearly seen on the scans. This technique is termed

CT nodule densitometry. Pixels denser than 100 HU indicate the presence of calcification.

High attenuation of a nodule or mass sometimes is seen using CT in patients who do not have calcification. This may be seen in patients with amiodarone toxicity resulting in focal organizing pneumonia: the drug contains iodine, which appears dense. Patients with conglomerate masses from talcosis may show high attenuation due to the talc.

Fat

The presence of fat in an SPN may be diagnosed accurately only on HRCT. On HRCT, fat can be accurately diagnosed if low CT numbers are seen (-40 to -120 HU). This most likely indicates the presence of hamartoma (see

Figs. 3-49 and

3-51 in

Chapter 3), lipoma, or lipoid pneumonia (see

Figs. 20-1 and

20-2 in

Chapter 20). On occasion, histoplasmoma may show fat deposition with growth (

Table 9-10). Nearly 65% of hamartomas show fat on HRCT, sometimes in association with dense popcorn calcification or flecks of calcium. The presence of fat within a lung nodule is sufficient for calling it benign, although follow-up is appropriate.

Low (Water or Fluid) Attenuation

Benign cystic lesions, such as pulmonary bronchogenic cyst, sequestration, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), or a fluid-filled cyst or bulla (

Table 9-11), occasionally may be diagnosed on CT by their low attenuation (0 to 20 HU) and very thin or invisible walls (see

Fig. 1-6 in

Chapter 1). Mucoid impaction also may appear to be of low attenuation. On the other hand, bronchogenic cysts or other cystic lesions may have a higher attenuation because of their protein content. A hematoma may have the attenuation of blood (50 HU) or may have low attenuation, depending on its age.

A necrotic neoplasm, conglomerate mass, or lung abscess or infarction may have a low attenuation center on CT, but these lesions have a thick and perceptible wall.

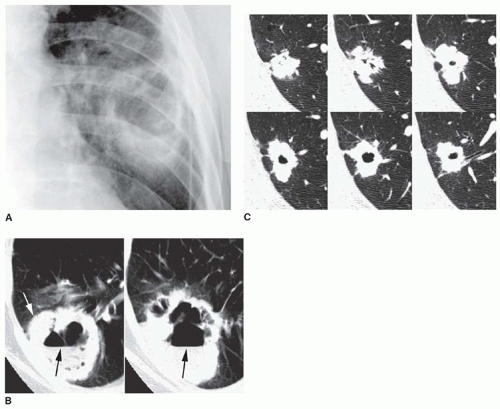

Contrast Enhancement

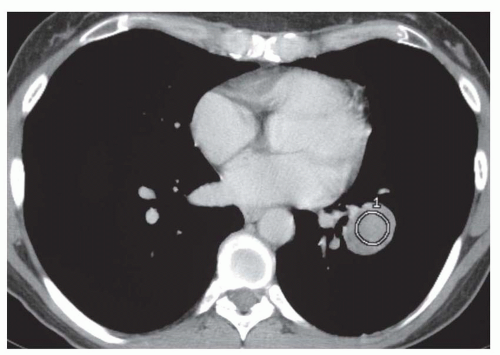

Cancers have a greater tendency to opacify following contrast infusion than do some types of benign nodules. Specific contrast enhancement techniques have been suggested to help diagnose malignancy. When using these techniques, sequential thin-collimation scans must be obtained through the center of a lung nodule for several minutes following contrast injection. Most SPNs show peak enhancement at either 3 or 4 minutes.

One currently recommended protocol uses scans at 1 minute intervals for 4 minutes following the start of the injection of 420 mg iodine/kg (usually 75 to 125 mL) at a rate of 2 mL/s. A region of interest encompassing about 60% of the nodule diameter is used to measure enhancement.

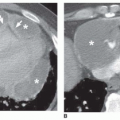

Using this protocol, carcinomas enhance by 14 to 165 HU (median, 38 HU;

Fig. 9-21) and benign lesions exhibit a change in CT number of -20 to 96 HU (median, 10 HU). Using an enhancement of 15 HU or more to suggest

malignancy, this test has a sensitivity of 98%, specificity of 58%, and accuracy of 77%. Specific benign lesions that show significant enhancement include active granulomas, inflammatory lesions, focal pneumonias, and some benign tumors such as hamartoma (

Fig. 9-22;

Table 9-12). Round atelectasis tends to enhance densely, as does any area of atelectasis.

It would seem most appropriate to use this technique when a nodule does not show typical findings of malignancy (e.g., spiculation, nodularity, cavitation, or growth) or typical features of a specific benign lesion. In such patients, this technique may help select which patients require surgery (i.e., if enhancement is present) or which can just be followed up carefully (i.e., if enhancement is absent).