Abstract

The solitary pulmonary nodule is a common challenge for the radiologist. Size, location, and attenuation are important characteristics in determining perception and detectability of a nodule. Computed tomography (CT) has been proven to be more sensitive for nodule detection and has been established as the procedure of choice for lung cancer screening. CT has expanded our understanding of nodules by revealing that ground glass nodules and mixed ground glass nodules with a solid component may precede the development of solid nodules. The list of possible diagnoses is long, but lung cancer is the most critical diagnosis for a solitary pulmonary nodule.

Keywords

adenocarcinoma insitu, arteriovenous malformation, carcinoid, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), hamartoma, histoplasmoma, intrapulmonary lymph node, invasive adenocarcinoma, lung cancer, lymphoma, pseudotumor, solitary metastases, tuberculoma

Questions

- 1.

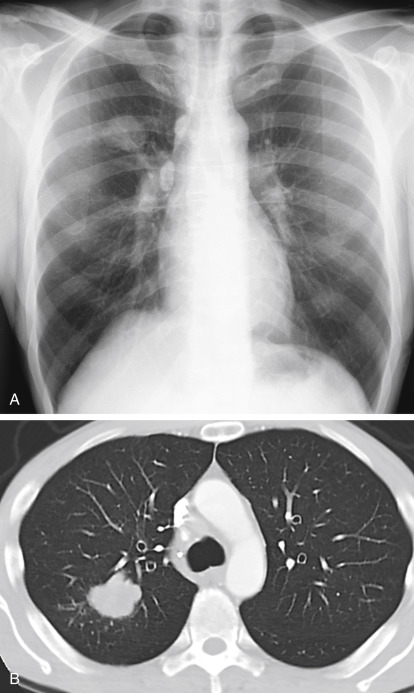

Refer to Fig. 20.1, A and B . Which one of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

- a.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma.

- b.

Adenocarcinoma in situ.

- c.

Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

- d.

Invasive adenocarcinoma.

- e.

Lymphoma.

Fig. 20.1

- a.

- 2.

The changing pattern illustrated in Fig. 20.2, A and B , is most suspicious for which one of the following?

- a.

Carcinoid.

- b.

Granuloma.

- c.

Hamartoma.

- d.

Lung cancer.

- e.

Solitary metastasis.

Fig. 20.2

- a.

- 3.

Which of the following statements regarding adenocarcinoma in situ are true?

- a.

Most often not visible on the chest radiograph.

- b.

Ground-glass opacity measuring 5 mm to 3 cm.

- c.

Has no solid components.

- d.

CT may show pulmonary vessels in the nodule.

- e.

All of the above.

- a.

- 4.

Which one of the following statements regarding carcinoid tumors is true?

- a.

Commonly suspected because of carcinoid syndrome.

- b.

Benign bronchial tumor.

- c.

Malignant neuroendocrine tumor.

- d.

Most commonly presents as a peripheral nodule.

- e.

Constitutes 15% to 20% of primary lung cancers.

- a.

- 5.

Which one of the following features of a peripheral nodule would be most diagnostic?

- a.

Spiculated borders.

- b.

Air bronchograms.

- c.

Central calcification.

- d.

Central cavitation.

- e.

Eccentric calcification.

- a.

Discussion

Primary lung cancer is the most critical cause of a solitary pulmonary nodule, but the list of possible causes is long ( Chart 20.1 ). Fortunately, the list of common causes is much shorter ( Chart 20.2 ). Healed granulomas from tuberculosis and fungal infections are the most common cause of a pulmonary nodule. These are benign and indicate prior infection but their diagnosis is important because they must be distinguished from malignant nodules. 613 The radiology report should emphasize the most serious of the possible diagnoses, offer a short differential diagnosis, and help the referring provider develop a plan to confirm the correct diagnosis.

- I.

Neoplasms

- A.

Malignant

- 1.

Primary lung cancer (see Chart 20.4 ) 234 , 477 , 479 , 598

- 2.

Metastasis (e.g., kidney, colon, ovary, testis, Wilms tumor sarcoma) 197 , 325

- 3.

Carcinoid (typical and atypical)

- 4.

- 5.

Primary sarcoma of lung

- 6.

Plasmacytoma (primary or secondary)

- 1.

- B.

- 1.

Hamartoma

- 2.

Chondroma

- 3.

Arteriovenous malformation 456

- 4.

Lipoma (usually a pleural lesion)

- 5.

- 6.

Leiomyoma

- 7.

Hemangioma

- 8.

Intrapulmonary lymph node

- 9.

Endometrioma

- 10.

Fibroma

- 11.

Neural tumor (schwannoma and neurofibroma)

- 12.

Paraganglioma (chemodectoma)

- 1.

- A.

- II.

Inflammatory diseases

- A.

Granuloma 590

- 1.

Tuberculosis 388

- 2.

- 3.

Coccidioidomycosis

- 4.

Cryptococcosis (torulosis) 200 , 229 , 346 , 380

- 5.

Nocardiosis

- 6.

Talc

- 7.

Dirofilaria immitis (dog heartworm)

- 8.

Gumma

- 9.

Atypical measles infection

- 10.

Sarcoidosis 432

- 11.

Q fever 385

- 1.

- B.

Abscess

- C.

Hydatid cyst (fluid-filled)

- D.

Bronchiectatic cyst (fluid-filled)

- E.

Fungus ball

- F.

Organizing pneumonia, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), atypical measles pneumonia, 661 cytomegalic inclusion virus 455

- G.

Inflammatory pseudotumor (e.g., fibroxanthoma, histiocytoma, plasma cell granuloma, 190 , 409 sclerosing hemangioma) 10

- H.

Bronchocele 334 and mucoid impaction 392

- I.

- A.

- III.

Vascular diseases

- A.

- B.

Pulmonary vein varix or anomaly 38

- C.

Rheumatoid nodule

- D.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis)

- E.

- A.

- IV.

Developmental abnormalities

- A.

Bronchogenic cyst (fluid-filled) 463

- B.

Pulmonary sequestration

- A.

- V.

Inhalational diseases

- A.

Silicosis (conglomerate mass) 636

- B.

Mucoid impaction (allergic aspergillosis)

- C.

Paraffinoma (lipoid granuloma)

- D.

Aspirated foreign body

- A.

- VI.

Other

- A.

Hematoma

- B.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis

- C.

Emphysematous bulla (fluid-filled)

- D.

Thrombolytic therapy

- E.

Mimicking opacities 467

- 1.

Fluid in interlobar fissure

- 2.

Mediastinal mass

- 3.

Pleural mass (mesothelioma)

- 4.

Chest wall opacities (e.g., nipple, rib lesion, skin tumor)

- 5.

Artifacts

- 6.

Atelectasis with bullous emphysema 188

- 1.

- F.

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder 119 , 224

- G.

- A.

- I.

Neoplasms

- A.

Malignant

- 1.

Primary lung tumor (see Chart 20.4 ) 222 , 234

- 2.

Metastasis 325

- 1.

- B.

Benign (less common) 135

- 1.

Hamartoma

- 2.

Arteriovenous malformation

- 1.

- A.

- II.

Infections

- III.

Vascular disease

- A.

Infarct

- A.

- IV.

Mimicking opacities

- A.

Artifacts (e.g., button, snap) 467 , 469

- B.

Nipple shadow

- C.

Skin and subcutaneous lesions (e.g., mole, neurofibroma, lipoma)

- D.

Pleural lesions (loculated effusion or pleural mass)

- E.

- A.

Neoplasms

Lung Cancer

Perception is the first challenge confronting the radiologist in the task of lung cancer detection. 23 , 202 , 400 Good radiographic technique is essential for the detection of a pulmonary nodule. Woodring’s review 651 of the pitfalls in the diagnosis of lung cancer reminds us that detection of small pulmonary nodules requires good technique and careful review of the radiograph. The standard chest examination includes a frontal radiograph, taken with the patient facing the detector and the radiograph beam passing posterior to anterior, and a lateral radiograph, which is taken with the patient’s left side against the detector (left lateral). Both images should be taken at maximum inspiration. There is no perfect technique for all cases. The ideal frontal chest radiograph provides good detail of the central structures (e.g., trachea, carina, thoracic spine, intervertebral disk). This permits visualization of the normal vasculature posterior to the heart and thus makes detection of nodules posterior to the heart and posterior to the domes of the diaphragm possible. Adequate penetration of these opaque areas must be done while preserving good visualization of the peripheral vascular markings. This cannot be accomplished with low peak kilovoltage (kVp) techniques. 83 , 505 For example, a posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph taken at 60 kVp will be too light for adequate evaluation of the mediastinum. With the low-kVp technique, the lungs will be black if the mediastinum and left lower lobe are adequately penetrated. This has led to the development of higher kVp techniques for standard chest radiography. It is generally agreed that the optimal kVp is in the range of 120 to 150 kVp. This is a major limiting feature of portable chest radiography, which makes it inadequate for the exclusion of pulmonary nodules. The only major disadvantage of the high-kVp technique is the reduced visibility of calcium.

Viewing time for the detection of a nodule on a chest radiograph by an experienced radiologist may be surprisingly short, but it requires a trained, systematic visual search. Kundel et al. 320 demonstrated that obvious cancers are often detected with flash viewing of the image and that subtle cancers may be detected with as short a viewing time as 4 seconds. It was even suggested that prolonged viewing of longer than 10 seconds does not improve the number of true-positive results but increases false-positive results. Detection of less conspicuous nodules is improved by knowledge of the anatomic areas in which lesions are likely to be obscured. Comparisons are vital. For example, the right and left pulmonary arteries should be symmetrically opaque. Asymmetric opacity at the junction of the costal cartilage and the rib must be carefully scrutinized. Nodules in the medial portions of the lung may be obscured by large vessels or the heart and may thus be more easily detected on the lateral than on the PA view ( Fig 20.3, A and B ). Obvious abnormalities that may even be insignificant sometimes capture the viewer’s attention and interfere with the detection of a subtle lung cancer. After detecting an abnormality, observers should make a conscious effort to complete the review of the examination and avoid the phenomenon of satisfaction of search as a cause of missed abnormalities. 644 Comparisons with previous examinations also enhance the visual search and may make subtle or minimal opacities more detectable.