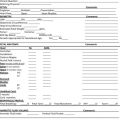

Students who successfully complete this chapter will be able to do the following: • Discuss the prevalence, causes, and risks of musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) in the field of sonography. • Identify the causes and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSD) and musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) associated with scanning. • Describe the biologic tissue response to improper posture and scanning techniques. • Explain at least three factors that influence work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSD) and musculoskeletal injuries (MSI). • Discuss ergonomic methods of prevention of MSIs. • List the major components of a safe scanning environment. • Name three strategies for combating unhealthy stress in the workplace. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, more than three fourths of the sonography workforce reported experiencing pain while scanning, and one in four sonographers sustained career-ending injuries.1 Although their injuries were varied, a major contributing cause was the poor conditions in which they worked. The sonography community is now aware of the importance of ergonomics, the creation of a safe working environment, and is devoted to finding solutions to the work-related injuries and job-related problems encountered by sonographers. The most common work-related injuries among sonographers are tendonitis and tenosynovitis of the shoulder, cervical spine, neck, wrist, and lower back. These injuries are related directly to prolonged periods of arm abduction and muscle loading coupled with constant transducer pressure during scanning. Contributing to these repetitive strain injuries (RSIs) are (1) the use of poorly designed ultrasound equipment and stretchers; (2) improper body mechanics while scanning; (3) procedure duration; (4) inappropriate force; (5) insufficient rest/breaks; and (6) repetition of the same type of study for long periods during the workday. Clearly, changes and modifications in equipment and the duration and frequency of sonographic examinations are essential to prevent or significantly reduce such injuries. Sonographers must learn to protect themselves by avoiding situations that lead to MSIs, and sonography training should include instruction in safe scanning techniques and information about injury and prevention (Box 4-1). The most common sites of sonographer pain or injury are the neck, back, hips, shoulder, wrist, hands, fingers, and feet (Box 4-2). The primary causes of all of these injuries are associated with one or more of the following activities: repetition, force, and awkward postures. Awkward posture refers to the deviation of the skeletal bones and joints from a neutral or natural position (Box 4-3). The risk of injury increases with the number of times and the greater length of time that a joint deviates from its natural position. Specific activities that lead to pain and injury are as follows: Sonographer work-related injuries typically include muscle strains and tears, ligament sprains, joint and tendon inflammation, pinched nerves, and spinal disc degeneration. MSIs can be difficult to diagnose, and although doctors can perform clinical tests for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), with many other MSIs, evaluation is based solely on whether someone is in pain, and pain is subjective. Box 4-4 lists the signs that a sonographer may be developing an MSI. The symptoms of neurologic TOS are variable, depending on which structures are compressed: The symptoms of vascular TOS are the following: • Cyanotic (bluish) appearance of the hand • Arm pain/swelling (possible blood clots) • Throbbing lump near clavicle • Pallor (lack of color) in one or more fingers or the entire hand The upper extremities, especially the wrists and the hands, are an anatomically complex collection of bones, muscles, tendons, and nerves. All of these structures are essential to work activities and are increasingly subject to acute and chronic mechanical injuries (Box 4-5). Among sonographers, upper extremity injury is associated most often with the use of poorly designed transducers or improperly holding or excessively gripping the transducer. The resulting injuries are tendonitis, tenosynovitis, or tunnel syndromes. In addition, damage to the elbow, epicondylitis (tennis elbow), or posterior impingement syndrome of the elbow can be sustained. Lack of tendon elasticity and constant pulling on the tendon attachments to the bone make tendon attachments susceptible to microscopic, low-level tearing. Such tearing produces the inflammation and irritation known as tendonitis. Tendonitis (also spelled tendinitis) is variable, striking the most often used areas. Symptomatically, tendonitis ranges from aching pain and stiffness in the local area of the tendon to a burning sensation surrounding the entire joint around an inflamed tendon. Pain usually worsens during and after activity, and the tendon/joint area typically becomes stiffer the next day. With proper care, tendon pain should lessen over 3 to 4 weeks. The healing process continues, however, and may not peak until 6 weeks after the initial injury. This is due to the formation of scar tissue, which initially acts as a glue to bond the tissue back together. Scar tissue will continue to form past 6 weeks in some cases and for as long as a year in severe cases. After 6 months the condition is considered chronic and is much more difficult to treat. The initial approach to treating tendonitis is to support and protect the tendons by bracing any tendon areas pulled on during use (Figure 4-1). Loosening up the tendon before use lessens pain and minimizes inflammation.

Sonographer Safety Issues

Prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries among sonographers

Ergonomics and work-related sonographer injury

Physiology and symptoms of work-related injury

Sites of injury

Lower Back Pain

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Extremities

Tendonitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine