Spine(II)

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is the anterior displacement of a vertebra relative to the vertebrae below, generally caused by a morphologic abnormality in the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch. Usually this consists of a defect in the isthmus of the vertebral arch between the superior and inferior articular processes (interarticular spondylolysis). Another possible cause is dysplasia characterized by elongation or shortening of the pars interarticularis. The prevalence of these two classic factors, with or without spondylolisthesis, is ~ 4–5%. The L4 or L5 vertebra is affected in ~ 90% of cases, with less frequent involvement of other lumbar or cervical vertebrae. An increased incidence of spondylolisthesis is found in gymnasts, ballet dancers, javelin throwers, weight lifters, and swimmers. Other causes of spondylolisthesis are listed in Table 8.3 .

Because the different forms are on a continuum and may coexist with one another, the classification in Table 8.3 is of limited clinical value. Spondylolisthesis with a degenerative cause is currently known as pseudospondylolisthesis and is considered a separate entity because of the absence of a vertebral arch defect.

The spondylolisthesis itself generally stops progressing after the cessation of skeletal growth. On the other hand, spondylolisthesis may lead to disc degeneration, which may in turn cause a slight progression of anterior slippage. It should also be noted that spondylolysis or isthmic dysplasia does not always lead to spondylolisthesis.

The diagnosis and follow-up of spondylolisthesis rely on lateral radiographs of the affected region. A standing radiograph (rather than supine) is recommended to detect any static changes caused by the process. It has been claimed that oblique radiographs of the lumbar spine in 45° rotation permit better evaluation of the pars interarticularis, but they rarely add information in patients with definite defects and high-grade spondylolisthesis and have been largely replaced by cross-sectional imaging studies.

At the cervical level, spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis most commonly affect the C6 vertebrae and are often accompanied by a median cleft in the neural arch and spinous process (spina bifida occulta). The slipped vertebra often shows a distorted shape with hypoplastic or aplastic pedicles, laminae, or articular processes.

As for the radiographic geometry of spondylolisthesis, methods have been devised for describing the anterior displacement of the vertebral body and for analyzing secondary static changes that may develop. As a rule, the latter methods can be applied and interpreted only for spondylolisthesis at the L5/S1 level.

Wiltse LL, Winter RB. Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65(6):768–772 Wiltse LL, Rothman SG. Lumbar and lumbosacral spondylolisthesis; classification, diagnosis and natural history. In: Wisel SW, Weinstein JN, Herkowitz HN et al, eds. Lumbar Spine. Vol. 2, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1996: 621–651Evaluating the Degree of Spondylolisthesis

Meyerding Classification

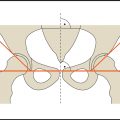

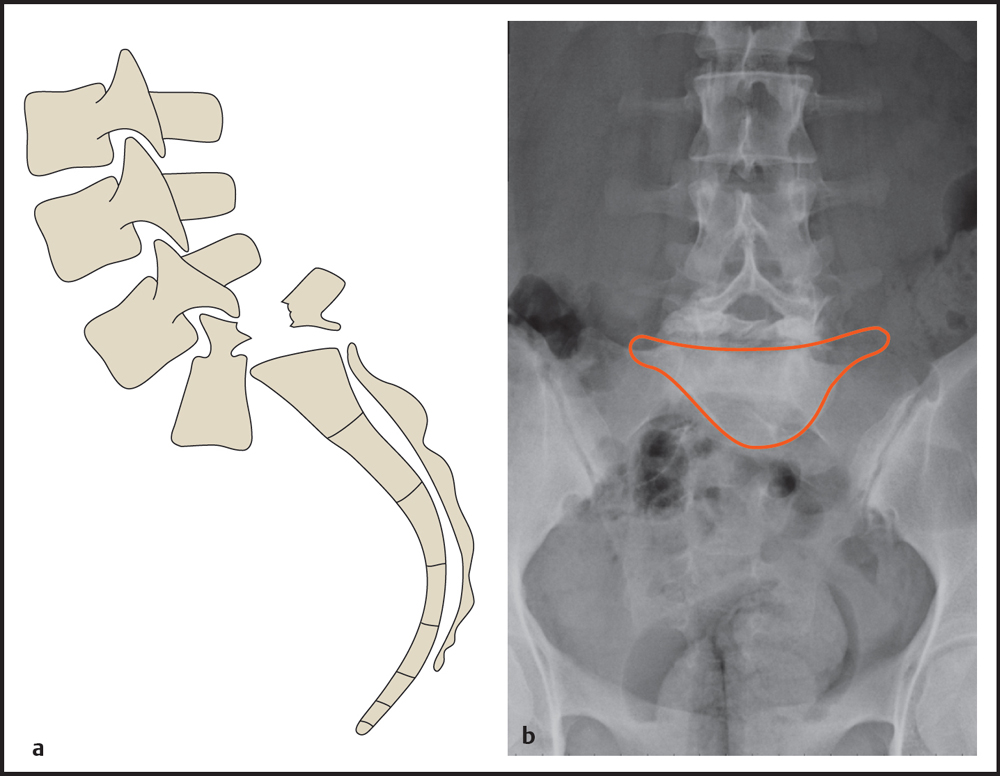

The anterior displacement of a vertebral body may be referred to as (o)listhesis, slip, or anterior translation. The Meyerding classification is the best-known system for grading the degree of anterior slip ( Fig. 8.14 ). In this system the endplate of the vertebral body below the slipped vertebra is divided into four equal segments. The relationship of the posteroinferior corner of the slipped vertebra to the quadrants of the adjacent endplate determines the degree of spondylolisthesis. Complete forward and downward slippage of the L5 vertebra (spondyloptosis) produces a classic “inverted Napoleon′s hat” sign in the AP radiograph ( Fig. 8.15 ).

Meyerding HW. Spondylolisthesis: surgical treatment and results. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1932;54:371–377Anterior Displacement

“Anterior displacement” as described by Taillard and later by Laurent expresses the percentage of vertebral slip relative to the underlying vertebral body ( Fig. 8.16a ). The distance of the posterior margin of the slipped vertebra from the posterior margin of the underlying vertebra (A) is divided by the length of the underlying vertebral body (B), and the result is multiplied by 100%.

Measurements may be distorted by the presence of a posterior spondylophyte or by posteroinferior dysplasia of the affected vertebra. Wiltse et al recommended the following technique for defining the posterior margin of the vertebral body in cases of this kind ( Fig. 8.16b ): First draw a line parallel to the anterior margin of the slipped vertebral body (a), then draw another line (b) along the upper endplate perpendicular to line a. The posterior margin is now defined by drawing a line c along the lower endplate that is parallel to line b and equal to it in length.

Most authors prefer Taillard′s “anterior displacement” method over the Meyerding classification owing to its greater accuracy. Measurements should be interpreted with caution, however, especially when evaluating small changes over time, as studies have shown up to 15% rates of interobserver and intraobserver variability (Danielson et al 1988, 1989).

Method of Laurent and Einola

The Laurent–Einola method measures vertebral slip as a percentage ( Fig. 8.17 ). The degree of spondylolisthesis is defined as the ratio of the anterior displacement of the affected vertebra to its sagittal diameter, multiplied by 100%. This method has not become established in clinical practice, however.

Laurent LE, Osterman K. Operative treatment of spondylolisthesis in young patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976;117:85–91

Evaluating Secondary Static Changes

The static changes that develop in the setting of spondylolisthesis can be evaluated by various angles that are useful for follow-up and selecting patients for operative treatment.

Lumbosacral Kyphosis Angle

The lumbosacral kyphosis angle of Dick ( Fig. 8.18a ; Dick and Schnebel 1988, Dick and Elke 1997) is found by measuring the angle between the superior margin of the affected vertebra and the posterior surface of the sacrum. For spondylolisthesis at L5/S1, a kyphosis angle < 85° indicates a significant forward shift of the center of gravity. The patient tries to compensate for this by straightening the pelvis and lordosing the rest of the spine to return the center of gravity to a more posterior position ( Fig. 8.18b ). This results in painful contracture of the lumbar paravertebral muscles and static problems that may require corrective surgery in severe cases.

Dick WT, Schnebel B. Severe spondylolisthesis. Reduction and internal fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;232:70–79 Dick W, Elke R. Significance of the sagittal profile and reposition of grade III–V spondylolisthesis. [Article in German] Orthopade 1997;26(9):774–780Ferguson Angle

Measurement of the Ferguson angle (also called the “sacrohorizontal angle”) might depict increased angulation between the lumbar spine and sacrum ( Fig. 8.19 ). The angle is measured between the upper endplate of S1 and a horizontal line. A value of ~ 34° is considered normal. Acute sacrum (sacrum acutum) describes a condition in which the static changes in advanced spondylolisthesis have led to increased lordosis and a decreased Ferguson angle. With an arched sacrum (sacrum arcuatum), the lumbosacral junction assumes a more curved shape due to an increase in the Ferguson angle. Besides spondylolisthesis, morphologic and postural changes are the most frequent causes of an acute or arched sacrum.

Wiltse LL, Winter RB. Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65(6):768–772

Sacral Inclination

Sacral inclination, or sacral tilt, describes the relationship of the sacrum to a vertical line in the sagittal plane ( Fig. 8.20 ). It is used to measure the statically induced angulation of the lumbosacral junction that occurs in L5/S1 spondylolisthesis. Sacral inclination is evaluated on a lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine by drawing a straight line along the posterior margin of S1 and measuring the angle between that line and a vertical plumb line. The posterior margin of S1 may be difficult to discern on poorly exposed films. In this case an alternative reference line can be drawn through the midpoints of the upper and lower endplates of S1. As the anterior slip progresses, sacral inclination will decrease because of compensatory straightening of the pelvis. When the angle falls below 35°, surgical correction of the kyphosis should be considered based on recommendations in the orthopedic literature.

Wiltse LL, Winter RB. Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65(6):768–772Sagittal Rotation

Sagittal rotation (also called roll, sagittal roll, or slip angle) can be determined by measuring the angle formed by the posterior margin of S1 and the anterior margin of L5 ( Fig. 8.21 ). An angle of ~ 30° is considered normal in children and adolescents. The former method of measuring the angle between the upper endplate of S1 and the lower endplate of L5 is no longer recommended because of its poor reliability when L5 is hypoplastic.

Lumbar Lordosis

As spondylolisthesis increases, there is a marked increase in the degree of associated lordosis, especially in patients with a grade 3 or 4 slip. In the case of an L5/S1 spondylolisthesis, the angle describing the lumbar lordosis is measured between the upper endplate of L1 and the upper endplate of L5 ( Fig. 8.22 ). With spondylolisthesis at the L4/L5 level, the upper endplate of L4 provides the lower reference line. The normal value (measured in a population without spondylolisthesis) is ~ 35°. It should be noted, however, that in patients with pronounced sagittal rotation of L5, the lordosis may extend up into the thoracic spine, making it necessary to distinguish “total” lordosis from lumbar lordosis.

Slim GP. Vertebral contour in spondylolisthesis. Br J Radiol 1973;46(544):250–254 Wiltse LL, Winter RB. Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65(6):768–772Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree