© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015

Andor W.J.M. Glaudemans, Rudi A.J.O. Dierckx, Jan L.M.A. Gielen and Johannes (Hans) Zwerver (eds.)Nuclear Medicine and Radiologic Imaging in Sports Injuries10.1007/978-3-662-46491-5_3737. Sports Injuries of the Foot

(1)

PodoFoot BVBA, Bruges, Belgium

(2)

MoveFIT-Sports Medicine Division, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

37.1 Introduction

37.1.1 Disorders at Digit Level

37.2.1 Osseous Disorders

37.2.2 Soft Tissue Disorders

Abstract

About 40–50 % of the general population will develop a foot disorder at some stage in their lives. Of these injuries, 90 % will concern the forefoot. This comprehensive chapter on injuries of the foot aims to discuss the most common foot injuries in either recreational or elite athletes. Although technological advances in nuclear medicine and radiology enable physicians to obtain a precise diagnosis and monitor the rehabilitation process, a sound understanding of the pathophysiology of these common foot injuries remains the basis for a successful diagnosis and treatment.

This chapter summarizes the most common foot problems that an athlete can encounter. In describing these foot pathologies, the foot is divided into six different zones. For each zone, a description of possible foot injuries is provided in a concise manner. After reading this chapter, the reader will have a better understanding of normal and abnormal foot anatomy in relation to the biomechanical etiology of common overuse injuries of the foot. Although this review is not intended to provide the reader with a complete overview of sports-related foot problems, it will assist clinicians in their differential diagnosis when requesting, e.g., a radiological examination.

37.1 Introduction

The prevalence and incidence of certain sports-related foot disorders varies tremendously with the type of sport. About 40–50 % of the general population will develop a foot disorder at some stage in their lives. Of these injuries, 90 % will concern the forefoot (Mann 1978). In order to understand the etiology of this wide range of sports-related foot pathology, technical and biomechanical knowledge of each sport is often a prerequisite. However, it also requires a firm knowledge of the anatomy of the foot.

In accordance, the objective of the present chapter is to provide the reader with a concise description of most common sports-related foot pathology and increase the reader’s understanding of normal and abnormal foot anatomy in relation to the biomechanical etiology of common overuse injuries of the foot.

37.1.1 Disorders at Digit Level

37.1.1.1 Turf Toe

Turf toe is an injury to the connective tissue of the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP) of the great toe. According to epidemiology, there are no differentiating ethno-cultural, sex-related, or age-related determinants connected to turf toe.

Turf toe can occur to any athlete if predisposing factors and the mechanism of injury are present at the time of injury. About 40–50 % of the general population will develop a foot disorder sometime in their lives. Of these injuries, 90 % will concern the forefoot (Mann 1978). The most common activities associated with turf toe are soccer, dance, or following a trauma to the great toe. The pathomechanics of this injury is typically a hyperextension of the MTP joint. It is rarely the result of hyperflexion. The abnormal forces applied to the first MTP joint at the time of injury result in varying degrees of sprain or disruption of supporting soft tissue structures, leading to the injury commonly referred to as turf toe. The extent of tissue disruption influences the treatment planning but can also be used to prognosticate recovery (Childs 2006). High-risk sports include judo, soccer, wrestling, rugby, cycling, gymnastics, and dancing (Allen et al. 2004; Demaj 2009).

37.1.1.2 Hallux Rigidus

This degenerative osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint occurs predominantly in men. The patient’s symptoms are often pain and stiffness in the first MTP joint while walking barefoot and in shoes. It is not uncommon that skin irritation and activity-related swelling over a dorsal osteophyte can be present on the first metatarsal head. To minimize discomfort, athletes often have to restrict their activities and modify their shoe wear selection (low heel, stiff sole, and larger toe box). Physical findings suggestive of hallux rigidus include (Alexander 1997; Root et al. 1977):

Enlargement of the first MTP joint due to a combination of osteophytes and soft tissue swelling.

Tenderness along the MTP joint line and palpable joint line osteophytes, particularly dorsally.

First MTP range of motion limitation with/without crepitus.

Initially, the pain can be provoked with stressed plantar flexion of the MTP. In a later stage, pain will occur with stressed dorsiflexion of the joint. In advanced cases, pain and crepitus are present when the first MTP joint is rotated in the frontal plane (positive grind test).

High-risk sports: soccer, gymnastics, and dancing.

37.1.1.3 Hallux Abducto Valgus

Pain associated with prominence of the medial eminence of the first metatarsal head (called a bunion) is often a problem in females with a wide forefoot who wear dress shoes with a narrow, constrictive toe box. Hallux valgus or the lateral deviation of the great toe is usually present and may result in additional discomfort due to impingement of the great and second toes. Although a hereditary cause is unknown, metatarsus primus varus may play an etiological role (Kilmartin and Wallace 1991), and patients often report a positive family history for hallux valgus problems. Despite the discomfort, athletes with hallux abducto valgus will often continue to wear aggravating shoes, either because their sport demands it or because they find shoes that will accommodate their deformity socially unacceptable. Individuals with severe deformities will experience pain in even the most forgiving shoes, and alleviation of the discomfort that these athletes experience over the bunion will often necessitate surgical intervention if corrective orthotics supporting the first ray and/or straight-lasted shoes do not alleviate the pain. Although radiographic findings are most important in deciding the appropriate surgical procedure, patient’s history and specific findings during a physical examination should be considered as well. One of the most common causes of failed bunion surgery is hallux rigidus, not being recognized prior to surgery (Alexander 1997; Root et al. 1977).

Coexisting hallux rigidus should be suspected if physical findings as previously described are present. Athletes with pure hallux valgus will localize their discomfort directly to the prominent medial eminence and usually have no discomfort walking barefoot due to lack of shoe irritation.

Bunion correction will do nothing to alleviate any component of the athletes pain related to inflammatory arthritis. The type of corrective procedure chosen depends on specific findings related to the deformity: Athletes with passively correctable lateral deviation of the hallux will, in most cases, be adequately treated with a less invasive distal metatarsal osteotomy and medial capsular reefing. Individuals with hallux valgus greater than 30°, pronation of the great toe, and fixed deformity usually require extensive soft tissue releases in addition to proximal osteotomy of the first metatarsal. Rigid lateral deviation and pronation of the hallux suggest fixed lateral positioning of the sesamoids with a lateral capsular contracture (Mertens 2012; Perera et al. 2011).

37.1.1.4 Tailor’s Bunion

Tailor’s bunion is a deformity of the 5th metatarsal position which produces an abnormally prominent 5th metatarsal head. Shearing between the unstable metatarsal head and overlying soft tissues fixed by shoe pressure results in an inflamed adventitious bursa called a tailor’s bunion. Besides an idiopathic condition, its etiology finds its basis in the following (Root et al. 1977):

1st factor: abnormal subtalar joint pronation during the midstance and early propulsive periods result in hypermobility of the 5th metatarsal. This hypermobility produces internal shearing between the 5th metatarsal head and the overlying soft tissue. This soft tissue is fixed by shoe pressure and cannot move with the hypermobile metatarsal. The latter may occur in sports activities that require stiff footwear such as, soccer, basketball, rugby, and volleyball. Properly fitting shoe (especially an appropriate width) is an absolute requirement for treating this condition.

2nd factor: any uncompensated varus position of the forefoot or rearfoot in a fully pronated foot, for example, no forefoot varus compensation for a rearfoot valgus.

3rd factor: a congenital plantar-flexed or dorsi-flexed fifth ray deformity.

37.2 Disorders of Midfoot and Forefoot Level

37.2.1 Osseous Disorders

37.2.1.1 March Fracture

The march fracture usually occurs at second ray level of the foot and is the result of a brutal overload such as a long march with an unprepared athlete. Initially, there is often a tolerable pain, which occurs during landing and loading of the second ray. Intolerable pain characteristically occurs at a progressively earlier stage of exercise as the condition develops. The pain worsens with athletes who keep training and pain occurs also during walking or even at rest. Sometimes, a clear swelling can be seen at the site of the pain (Verdonk 2006). Various bones may be affected including metatarsals and calcaneum. Stress fractures of the metatarsals may occur secondary to hallux valgus. In the early stages, these fractures may not be visible in plain radiographic views. In these cases, technetium bone scans or MRI scans are useful (Greida 1988; Bjerregaard and Siggaard 1981).

37.2.1.2 Morbus Köhler I

The Köhler 1 disease is an avascular necrosis of the navicular bone with collapse seen in the growing child usually between 4 and 9 years old. Its etiology is similar to Perthes’ disease at hip level and Kienböck’s disease at the level of lunate bone of the wrist. The symptoms are sudden occurrence of pain, joint movement sensitivity or restriction, and swelling. In a more advanced stage, muscle atrophy of the leg will be present. A plain radiographic view confirms the diagnosis. The disease evolves without sequelae (Alexander 1997; Root et al. 1977; Verdonk 2006).

37.2.1.3 Morbus Köhler II

37.2.1.4 Accessory Navicular Syndrome

The accessory navicular bone is an extra bone or piece of cartilage that is incorporated within the posterior tibial tendon located on the inner side of the foot just above the arch. The condition presents at birth (congenital) and is not part of normal bone structure and therefore not present in most athletes. However, athletes who have an accessory navicular bone often are unaware. Some people with this extra bone develop a painful condition known as accessory navicular bone syndrome when the bone and/or posterior tibial tendon is overloaded. On radiographs, this accessory navicular bone is categorized in three different types; only type II (with syndesmosis of synchondrosis of the accessory bone with the navicular bone) and type III (synostosis of the accessory bone with the navicular bone to form an elongated navicular bone also called os cornutum) are related to symptoms, and overuse of the posterior tibial tendon and spring ligament may have constitutional flatfeet or develop flatfeet. Type I accessory navicular bone constitutes of a small rounded bone fragment in the distal posterior tibial tendon without relationship to the navicular bone. Symptomatic type II and III accessory navicular bone can result from any of the following (Chi et al. 2009; Lobo and Geisenberg 2007):

Traumatic cause: as in a foot or ankle sprain

Chronic irritation: from shoes or other footwear rubbing against the accessory bone

Overuse: excessive rise in activity, constitutional flatfeet, and obesity

Many athletes with accessory navicular syndrome also have acquired or constitutional pes planovalgus feet. Type II and III accessory navicular bone results in an abbreviation of the inframalleolar part of the tibialis posterior tendon putting more strain the tendon, and also having a constitutional flat foot puts more strain on the posterior tibial tendon, which can produce inflammation or irritation of the accessory navicular bone (Lobo and Geisenberg 2007).

Acquired flatfeet is a result of spring ligament insufficiency accompanied by tibialis posterior tendinopathy and/or tenovaginitis. Adolescence is a common time for the symptoms first to appear. This is a time when bones are maturing and cartilage is developing into bone. Sometimes, however, the symptoms do not occur until adulthood.

Symptoms of accessory navicular bone syndrome include:

A visible bony prominence on the midfoot more specifically on the inner side of the foot, just above the medial arch

Redness and swelling of the bony prominence

Vague pain or throbbing in the midfoot and medial arch, usually occurring during or after periods of physical activity

Acquired flatfoot

37.2.1.5 First Ray Disorder

Dudley J. Morton (1884–1960) was a physician, anatomist, and anthropologist. His work focused on the shortened first metatarsal, hypermobility of the first metatarsal segment, and correlation of first ray mechanics to excessive foot pronation. In his book, “The Human Foot, Its Evolution, Physiology, and Functional Disorders,” he describes first the load deformation of the first ray (Morton 1964).

He states that if the plantar ligaments of any segment are slack when the head of its metatarsal bones lies on the same plane as the others whose ligaments are taut, that segment will fail to share in the carriage of body weight. Morton believed that hypermobility of the first metatarsal affects the foot in several ways (Kirby 2012):

The second metatarsal has an increased burden since the first metatarsal fails to assume its normal share of weight.

The foot hyperpronates because the medial buttress is ineffective until slack in its ligaments is taken up as pronation increases.

As pronation advances, functional stresses are put increasingly on muscles on the inner side of the ankle, imposing them undue strain.

37.2.2 Soft Tissue Disorders

37.2.2.1 Morton’s Neuralgia

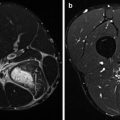

This condition was first described by Thomas George Morton (1835–1903). The medial and lateral plantar nerve joins in the foot between the head of metatarsals III and IV (third web space). There is elevated pressure at this location which could lead to interneuronal fibrosis in the course of the nerve also called Morton’s neuroma and/or intermetatarsal bursitis. Clinically, the patient complains of pain, especially in the morning and during activity in the foot flat – heel-off sequence of gait (Zollinger and Jacobs 1989). Symptoms are reproduced by the lateral squeeze test at the level of the metatarsal heads. Radiological differential diagnosis is made by dynamic ultrasound or MRI. Infiltration, minimally invasive US-guided techniques, and surgical neuroma removal are established therapies.

37.2.2.2 Metatarsalgia

Pain in the forefoot region is referred to as metatarsalgia, a nonspecific term. It refers to forefoot pain caused by a number of underlying pathologies. Common etiologies of pain originating in the joint (intra-articular) include capsulitis, capsular tear, synovitis, osteoarthritis, arthritis, and avascular necrosis of the metatarsal head or Freiberg’s disease. Frequent extra-articular causes include flexor tenosynovitis, interdigital neuroma (Morton’s neuroma), and metatarsal stress fracture. Effective treatment of metatarsalgia depends on making an accurate diagnosis of the underlying condition and establishing diagnosis-specific therapy. Radiographs are not particularly helpful in making an accurate diagnosis since many of the causes of forefoot pain originate in the soft tissues. A thorough physical examination is therefore warranted. Important features in the history of the patient are to be included to specify the diagnosis, and these include the character, location, and radiation of pain as well as specific aggravating factors. Likewise notable in the history taking are the location and degree of any swelling, as well as factors affecting its variability. A stepwise examination of the involved ray should include (Alexander 1997):

Inspection of the toe and forefoot for misalignment and swelling

Palpation of the dorsal and plantar aspect of the MTP joint, the long flexor tendon proximal and distal to the joint, the dorsal metatarsal neck and shaft, and the web and distal intermetatarsal space for tenderness and bone or soft tissue deformity

37.2.2.3 Splayfoot

An abnormal transverse plane spreading of the metatarsus that results in a pathologically increased width of the forefoot is commonly called splayfoot. In most cases, abnormally large intermetatarsal angulations develop. However, the primary spreading occurs between the first and second and between the fourth and fifth metatarsals. The splayfoot involves the three cuneiforms in conjunction with the five metatarsals. The pathomechanics can be described as the result of the following factors (Root et al. 1977):

1st factor: function loss of the transverse pedis muscle.

2nd factor: abnormal subtalar joint pronation that causes eversion of the foot during propulsion.

3rd factor: metatarsus primus adductus deformity is an acquired condition that is weakly associated with caused by hallux abductovalgus deformity. It results in a very large abnormal angulation between the first and second metatarsals.

37.3 Disorders at the Level of the Plantar Side of the Foot

37.3.1 Musculotendinous Disorders at the Level of the Plantar Foot

37.3.1.1 Plantar Fasciopathy

More recently, the term plantar fasciosis has been advocated to de-emphasize the presumed inflammatory component and reiterate the degenerative nature of histological observations at the calcaneal enthesis. The plantar fascia, or aponeurosis, spans the arch of the foot. It consists of three components: medial, central, and lateral. They originate from the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and blend distally with the plantar soft tissues of the MTP joint complex and anchor into the phalangeal bases. Several biomechanical functions are attributed of the plantar fascia (Kirby 2012):

Serves to stiffen medial and lateral longitudinal arches and reduce longitudinal arch flattening

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree