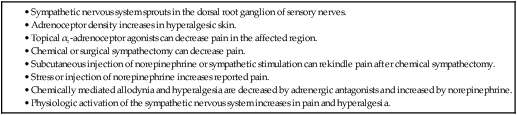

The first reported block of the sympathetic trunk was by Sellheim in 1905, and this was followed later by Lawen, Kappis, and Finsterer. True indications and technique remained vague until White established some rudimentary guidelines in the early 1930s.1 As regional anesthesia became more popular and our knowledge of pain syndromes increased, blockade of the stellate ganglion has seen increased application. The stellate ganglion block (SGB) is a simple, effective means of treating a wide variety of pain types that occur in the upper extremities, upper thorax, face, and neck. Incorporating systemic medications, physical therapy, and psychological therapy with SGB often produces better outcomes. • Limb ischemia including Raynaud phenomenon, arterial vasospasm • Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS, also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) • Neuropathic pain and vasospasm including Raynaud phenomenon • Posttraumatic stress disorder and postmenopausal hot flashes are possible future indications. SGB can be a part of treatment for many pain syndromes and symptoms; it leads to vasodilation in the upper extremity. Thus, pain syndromes like Raynaud disease and the Meniere triad have been alleviated via interruption of the sympathetic nervous system at the stellate ganglion. Treatment of pain secondary to upper extremity arterial thrombosis and frostbite has been documented. Furthermore, SGB can be efficacious in salvaging upper extremity ischemia caused by either extravasation of vasopressors or accidental intraarterial injection.2 SGB interrupts the sympathetic nervous system outflow to the upper extremity, which led to its historical use in the diagnosis and treatment of CRPS. There are two types of CRPS: CRPS-I, also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, has no specific nerve injury, whereas CRPS-II, also known as causalgia, can be attributed to injury to a specific nerve. SGB can ameliorate CRPS symptoms in the upper extremity, upper thorax, face, and neck.3 SGB has also been used to prevent postoperative recurrence of CRPS after upper extremity surgery in patients with resolved CRPS.4 Kakazu and Julka showed that SGB can effectively treat postoperative pain.5 SGB is most commonly used to treat chronic neuropathic pain,6 the rationale being that ephaptic connections can develop between the autonomic and somatic nervous system, especially after nerve injury.7 The link between the sympathetic efferent and somatosensory afferent nervous system has been demonstrated in both neuropathic and inflammatory conditions (Table e164-1). In addition, SGB has been used as a treatment for both acute herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia of the face and lower cervical/upper thoracic regions.8,9 Similarly, SGB has been used for phantom limb pain. Despite these facts, recent reviews question the effectiveness of therapies designed to inhibit sympathetic function in patients with CRPS.10,11 However, a recent systematic review of the topic found multiple trials demonstrating the effectiveness of SGB for CRPS and eventually scored it as a 2B+ therapy.12 TABLE e164-1 There are two emerging indications for SGB: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)13 and hot flashes in breast cancer patients.14,15 PTSD is a growing problem in the United Sates owing to service members returning home from conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Treatment of PTSD involves a multimodal approach, and the rationale for SGB is not obvious. However, SGB has connections to both the central systems responsible for anxiety, the hypothalamus and cardiovascular system, which mediate much of the systemic symptoms. Hot flashes after breast cancer treatment are common and cannot be treated with hormone replacement therapy. Lipov et al.14 initially described successful treatment of hot flashes with SGB, and Pachman et al. confirmed those results.15 Pachman’s study showed a 45% symptom reduction, but the mechanism remains unclear. • Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, or anticoagulant therapy • Contralateral pneumothorax or other pulmonary dysfunction • Contralateral vocal cord paralysis • Cardiomyopathy, recent myocardial infarction, or conduction defect There are few absolute contraindications to cervical sympathetic nerve blockade. Bleeding and infection are the primary risks of SGB. Anticoagulant therapy or coagulopathy increases the risk of uncontrolled bleeding after inadvertent vascular puncture. Ipsilateral pneumothorax can result after SGB from puncture of the dome of the lung, so contralateral pneumothorax or major pulmonary dysfunction is a contraindication. Ipsilateral vocal cord paralysis occurs frequently after SGB, thus contralateral vocal cord paralysis could lead to complete airway obstruction. Seizures can result from intravascular injection, but seizure disorder is not a contraindication to SGB. Patients with significant cardiac disease should not undergo SGB. The cardiac sympathetic fibers are interrupted by SGB, and a poorly conditioned heart may not be able to compensate for the abrupt changes. Researchers have demonstrated that left-sided sympathetic ganglion block may impair left ventricular function.16 Furthermore, bradycardia can be aggravated in patients with cardiac conduction defects. Finally, although not an absolute contraindication, worsening glaucoma symptoms have been reported in patients who have received multiple SGBs.

Stellate Ganglion Block

Clinical Relevance

Indications

Contraindications

Stellate Ganglion Block