Stroke

Nafi Aygun

Stroke is a sudden loss of neuronal function that can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. Ischemic stroke can be thrombotic, embolic, and due to diffuse hypoperfusion whereas hemorrhagic stroke can be intraparenchymal and subarachnoid. By convention, an ischemic event is classified as a transient ischemic attack (TIA) when the neurologic symptoms have resolved within 24 hours (although most neurologic symptoms lasting >20 minutes have positive findings on magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] suggesting permanent tissue damage); if the symptoms persist for more than 24 hours, the attack is termed an ischemic stroke.

Mechanisms of Ischemic Stroke

Thrombotic. Stenosis/occlusion of a large extracranial or intracranial vessel typically due to atherosclerosis leading to regional hypoperfusion. Nonatheromatous causes of arterial stenosis/occlusion include dissection and vasculitis.

Embolic. Approximately 20% of brain infarcts are due to emboli originating from the heart. Emboli may also arise from atheromatous plaques in the cerebral vessels (artery-to-artery embolism).

Watershed infarcts develop after episodes of global hypoperfusion, such as seen in cardiorespiratory arrest and prolonged hypotension.

Lacunar infarcts are small round infarcts in the internal capsules, thalami, and basal ganglia due to stenosis/occlusion of small penetrating vessels typically seen in the setting of chronic hypertension and diabetes.

Clinical Information

Symptoms and Signs.

It is important to determine precisely the temporal course and physical distribution of all neurologic symptoms. The symptoms of ischemic stroke have an all at once onset but may be either transient or permanent. TIAs due to stenosis are characteristically short in duration and highly stereotyped, often occurring in clusters. Artery-to-artery embolic TIAs may also be stereotypical and are usually more long lasting. Cardioembolic TIAs tend to be quite long lasting (from 1 to several hours), do not recur frequently, and may present with symptoms from different vascular territories in separate attacks. Vascular dissections may be neurologically asymptomatic, and may become symptomatic days to weeks after.

Carotid distribution TIA or stroke, suggestive symptoms:

Contralateral paralysis, weakness, or clumsiness.

Contralateral sensory loss: paresthesia and numbness.

Dysarthria (disturbance in articulation), not in isolation.

Ipsilateral amaurosis fugax (transient monocular blindness).

Rarely, homonymous hemianopsia.

Dysphasia (words not arranged in understandable way).

Vertebrobasilar distribution TIA or stroke, suggestive symptoms:

Weakness, bilateral or shifting.

Sensory loss, bilateral or shifting.

Homonymous hemianopsia.

Vertigo, diplopia, dysphagia, dysarthria, ataxia (two or more together).

“Top of the basilar artery” related symptoms including cardiorespiratory compromise, coma, “locked-in syndrome”—considered life threatening.

Symptoms, not evidence of TIA or stroke

include syncope, dizziness, confusion, incontinence, and generalized weakness.

Diagnostic Hints.

The combination of amaurosis fugax and ipsilateral focal neurologic signs, as those listed in the preceding text, is highly suggestive of carotid disease. Alternating neurologic symptoms, such as left then right hemiparesis, suggest vertebrobasilar disease, cardiac embolism, or diffuse vascular disease.

Clinical Differential Diagnosis.

A number of entities can resemble TIA or stroke clinically. Migraine presents with a march of neurologic symptoms that last 5-20 minutes. Seizures present with a rapid sequence of neurologic signs that last for less than a minute. Occasionally, primary and metastatic brain tumors produce transient focal neurologic findings. Supratentorial meningioma and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) can also mimic TIAs. Less common etiologies of strokelike symptoms include subacute subdural hematoma, especially in elderly patients, and amyloid angiopathy (AA), which usually causes lobar hemorrhages but can also present with recurrent episodes of sensory loss and ischemic infarctions.

Systemic disease entities that can mimic ischemic stroke include mitochondrial myopathy (e.g., MELAS), hypertensive encephalopathy, symptomatic hypoglycemia, and hyperventilation.

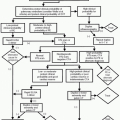

Treatment.

The most effective treatment is intravenous (IV) or intra-arterial (IA) thrombolysis which requires rapid diagnosis and introduction of the thrombolytic agent within 3-6 hours. The primary goal is to administer thrombolytics as quickly as possible; time is, neuron’.

Imaging

The goals of imaging in the setting of acute ischemic stroke are to determine the location and size of the infarct (irreversible damage), the size of hypoperfusing but viable brain tissue (penumbra), and the status of blood vessels. With this information, treatment can be tailored and prognosis can be determined.

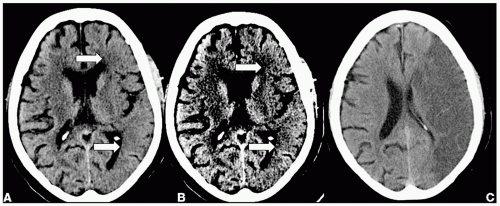

Imaging with Computed Tomography

Indications.

When evaluating a patient within a time window feasible for thrombolytic therapy, a standard noncontrast computed tomography (CT) is obtained to exclude hemorrhage, tumor, or other structural lesions which can preclude thrombolytic therapy. The CT findings in stroke evolve with time. Within the first 6 hours, early signs of infarction can be identified only in 30-40% of cases. With time, infarcts become more conspicuous. After 24 hours most infarcts are visible. Posterior fossa and brain stem infarcts are difficult to identify on CT owing to their small size and prominent beam hardening artifacts.

Protocol.

Standard evaluation includes noncontrast head CT, which must be reviewed in parenchymal, stroke, and subdural windows. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) can be obtained to evaluate the intra- and extracranial cerebral vessels. CT perfusion is a robust technique that can be performed immediately after CTA. CT perfusion is currently limited—in that one cannot image the entire brain.

Early infarct

Normal: majority of patients within the first few hours.

Subtle loss of gray-white differentiation: look at the insular ribbon and putamen.

Subtle brain swelling: look for asymmetry of cerebral sulci.

Hyperdense artery: indicates thrombus; look at the middle cerebral and basilar artery.

Acute/subacute infarct

Well-defined hypoattenuation conforming to a vascular territory.

Regional mass effect.

Midline shift if a large area is involved.

Hemorrhage into infarcted tissue.

Chronic infarct

Tissue loss (encephalomalacia) and regional volume loss.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree