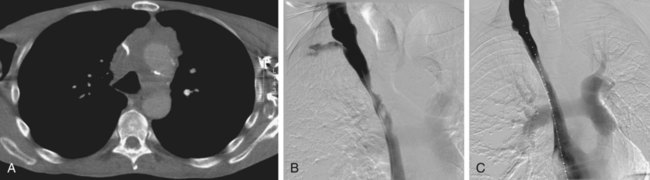

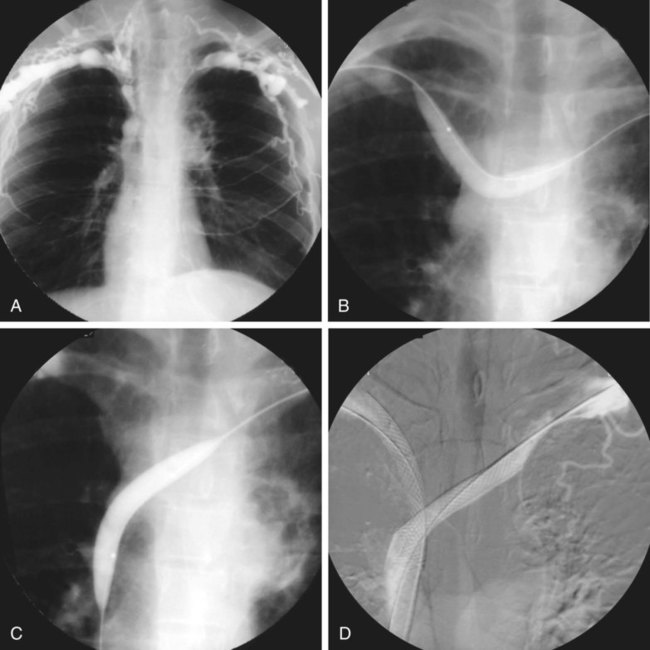

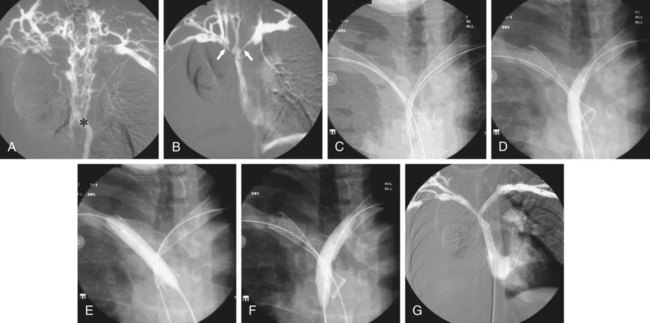

Chronic upper extremity (UE) occlusive disease and superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome can be debilitating to the patient and rewarding to treat with endovascular techniques.1 Chronic UE venous occlusion is more often due to a benign lesion, whereas SVC syndrome is more likely the result of malignant obstruction. The symptoms of chronic UE venous occlusive disease include arm swelling (especially with use or after creation of UE surgical dialysis access.2 Although the ipsilateral neck may be symptomatic, facial swelling does not occur with obstruction limited to the UE veins. Acute SVC syndrome is considered a medical emergency.3 Clinical symptoms include headache exacerbated by changes in position, disturbances in consciousness, facial edema, pain in the face and neck, blurred vision, retroorbital pressure, hoarseness, and orthopnea. Edema and pain can involve one or both arms. In patients with slowly progressive obstruction, collateral circulation develops to a variable degree over the chest wall and periscapular region. Acute SVC syndrome may be the first sign of a mediastinal tumor or may be seen later in the course of the disease.1 Interventional radiologists were early pioneers in the management of these challenging clinical entities.4,5 Most strictures of the SVC are of malignant origin. Tumors most commonly responsible for compression of the SVC and large mediastinal veins are bronchogenic carcinoma or small cell lung cancer with mediastinal lymph node enlargement caused by metastases from intrathoracic or extrathoracic malignancies, malignant lymphoma or Hodgkin disease, and tracheal malignancies. Other primary mediastinal tumors are less often encountered. The traditional method of treatment of SVC obstruction secondary to malignancy is radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of both. Such treatment is effective in about 90% of cases, but only after several days and with a recurrence rate of 20% even when the maximum permissible dose of radiation is used.1 Approximately 10% of all clinically significant SVC stenoses are due to a benign cause. The main causes of benign stenosis are catheter-related injury, mediastinal fibrosis, surgery, postanastomotic stenoses, infection, and radiotherapy.2–3 Conversely, most chronic stenoses or occlusion in the central arm veins are benign in nature and due to venous catheterization, instrumentation, and anatomic compression syndromes. Patients with acute malignant SVC syndrome that does not respond to radiation, or acute thrombosis of an underlying benign lesion should be considered for catheter-based intervention. Patients with chronic SVC stenosis who present with symptoms consistent with SVC syndrome are good candidates for stent placement. Patients with symptomatic chronic occlusive disease of the central UE veins may benefit from endovascular reconstruction, although anatomic compression syndromes should be surgically corrected first.6 • Basic angiographic catheters and guidewires are used. A hemostatic valve sheath up to size 10F is placed at the puncture site, depending on the size of the venous stents to be inserted. • Multipurpose or Cobra-shaped 5F catheters and hydrophilic 0.035-inch guidewires are mainly used to cross the venous obstruction. • For stent placement, the delivery catheter is pushed over a semi-rigid Amplatz-type guidewire for maximum stability during stent release. With regard to the venous anatomy of the upper extremities, brachiocephalic vessels, and SVC, please refer to Chapters 30 and 82. Stenoses located in the SVC or right innominate vein are most conveniently stented via a right femoral or right jugular approach (Fig. 99-1). Stenoses of the left innominate vein are treated from either a femoral or a left axillary approach. By using a rather unconventional puncture site for catheterization of the axillary vein—namely, at the junction between the axillary and subclavian veins—trauma to the brachial nervous plexus is avoided, particularly when large-diameter catheters are introduced. More direct access to the left innominate vein is also gained with use of this technique. As a general rule, venous stents should be placed sequentially, first in a distal position and then more proximally, in relation to the puncture site. When the confluence of the innominate veins is treated, the technique used depends on the anatomy and type of stents required. Soft and flexible stents can be placed simultaneously in the brachiocephalic vein and left innominate vein, with a parallel course in the SVC (Figs. 99-2 and 99-3). When more rigid stents are used, the SVC and right innominate vein are stented in a line, and stents are placed in the left innominate vein as close as possible to the caval axis. Transesophageal ultrasound can occasionally be helpful in accurate stent placement in the SVC, but it makes an otherwise simple procedure much more complicated.7,8 Duplex color ultrasound demonstrates stenosis or thrombosis of venous segments accessible to the probe. Loss of cardiac and respiratory variation in the internal jugular veins is suspicious for central obstruction. In most cases, venous-phase helical contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) with multiplanar reformatting or magnetic resonance (MR) venography can establish an unequivocal diagnosis of central venous stenosis or obstruction.9 Both modalities demonstrate the location and extent of disease and also show the collateral network. However, venographic demonstration of the stenosis and collateral pathways remains mandatory immediately before treatment. Venography confirms the location and extent of the stenosis, endoluminal thrombus, or tumor proliferation; the extent of collateral circulation; its hemodynamic significance; and any congenital variants that have to be taken into consideration when planning stent placement. Superior venacavography can be performed by simultaneous bilateral injection of contrast into the basilic or a more peripheral vein in the upper limb or jugular veins.

Superior Vena Cava Occlusive Disease

Malignant Obstruction

Benign Obstruction

Indications for Intervention

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Radiographic Technique

Superior Vena Cava Occlusive Disease