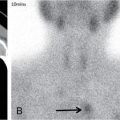

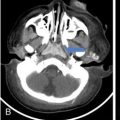

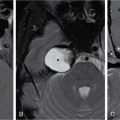

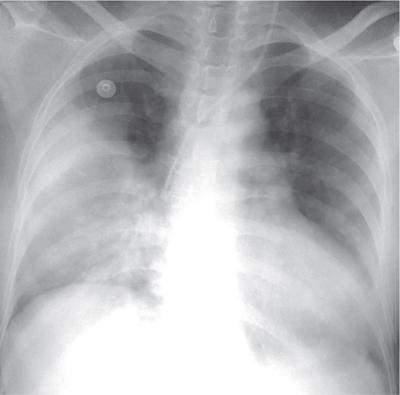

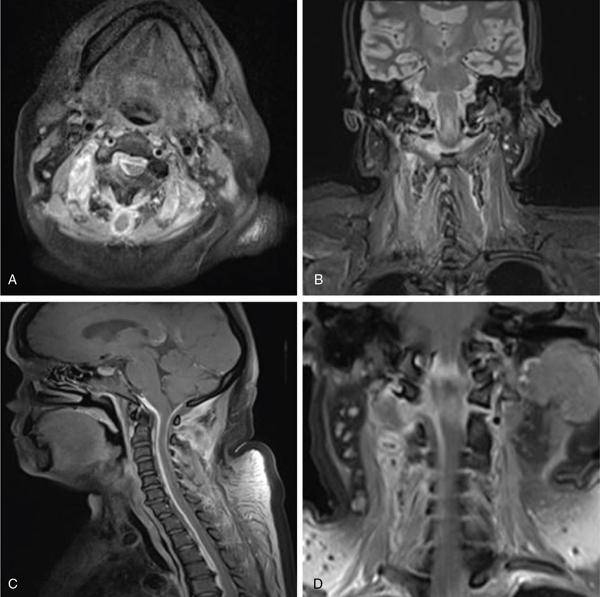

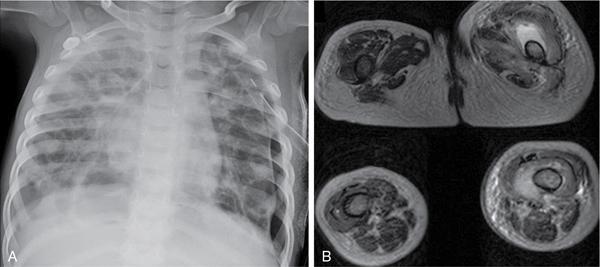

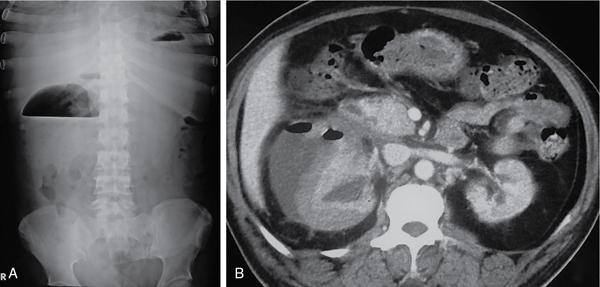

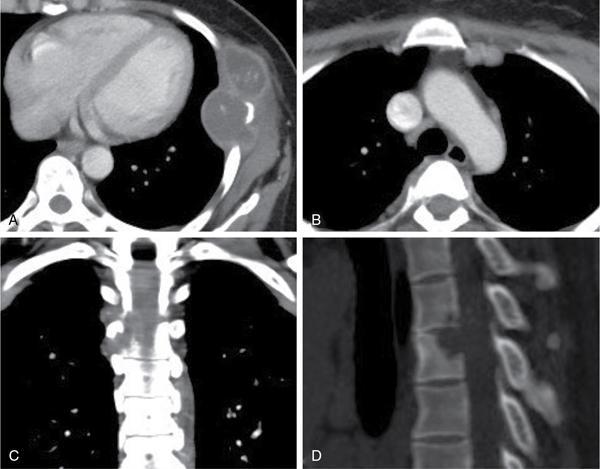

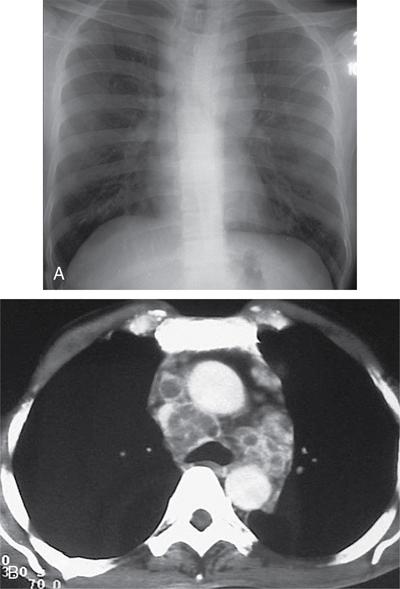

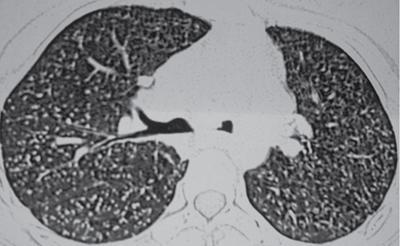

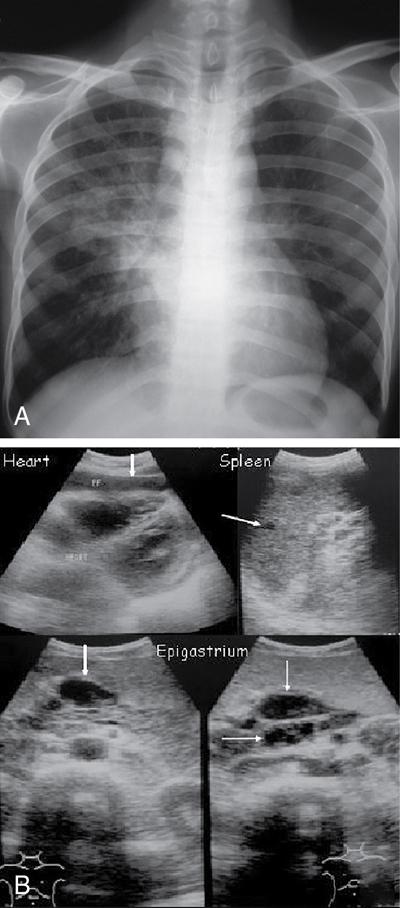

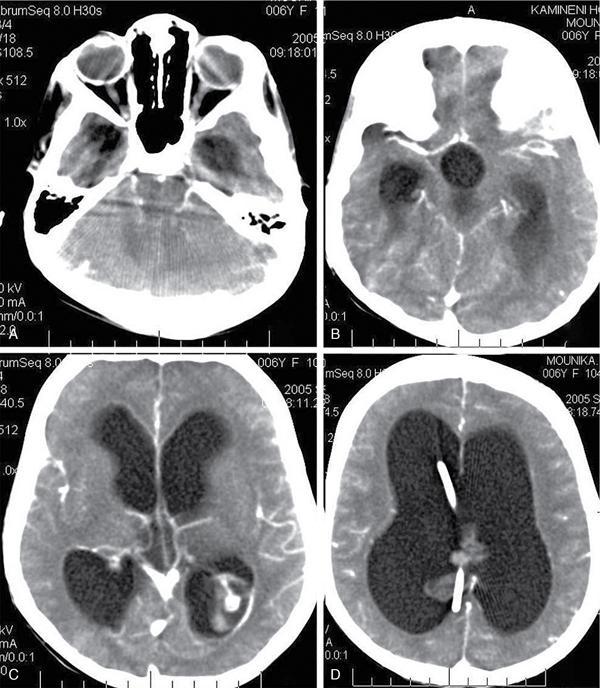

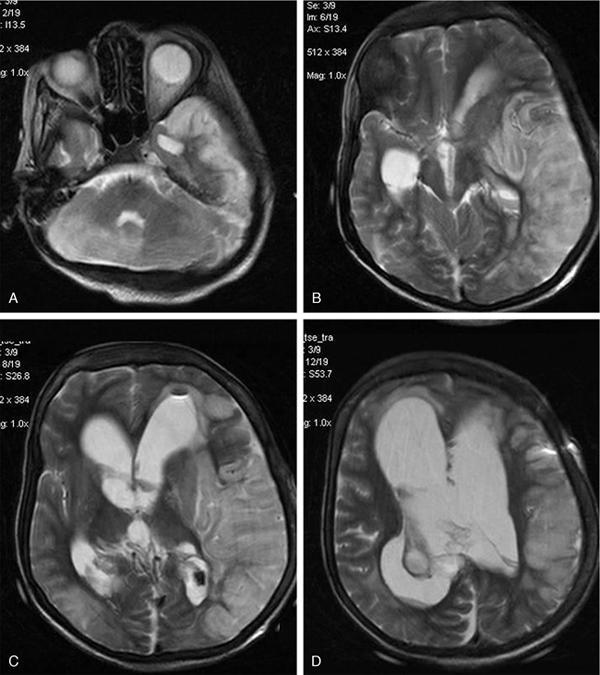

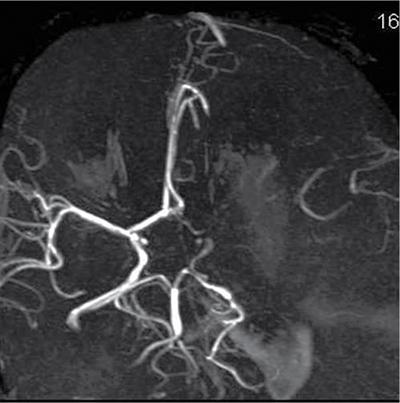

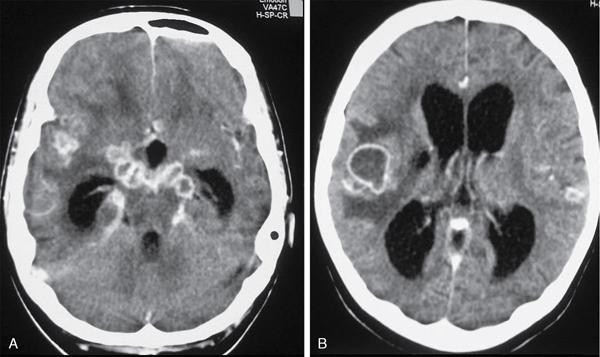

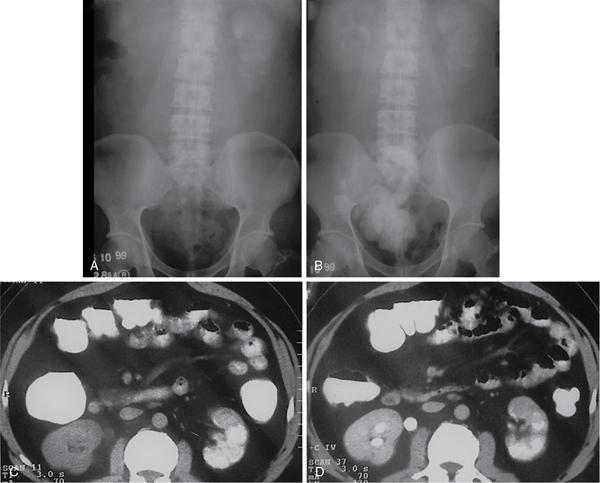

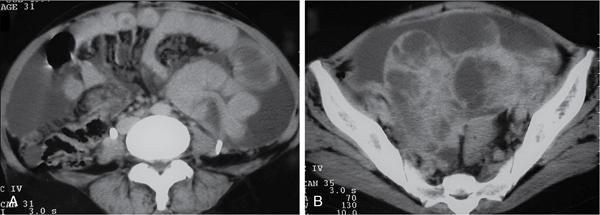

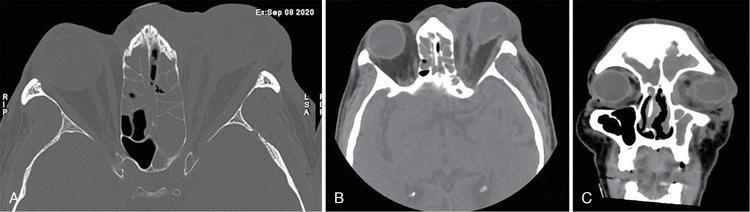

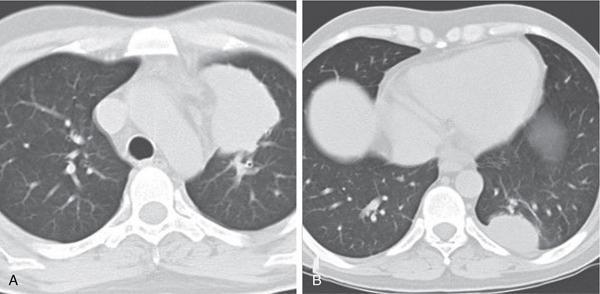

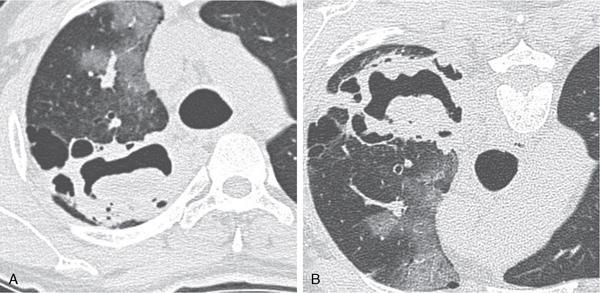

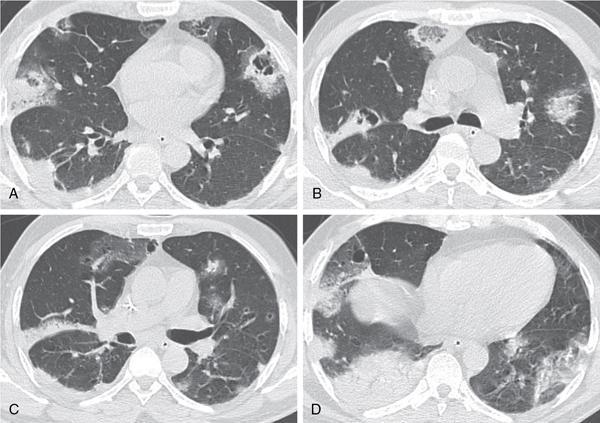

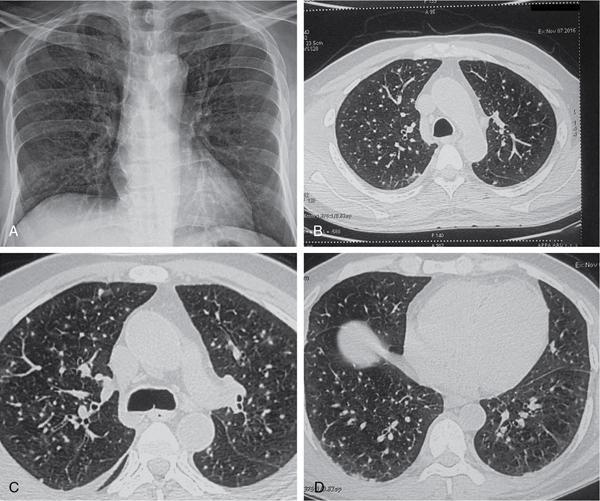

N. Eshwar Chandra, Annapurna Srirambhatla, Madhavi Latha Gundamaraju, N. Chidambaranathan Infections or infestations typically involve a single organ or a system. However, in a certain percentage of patients, especially with weak defenses, they may involve multiple organs or sometimes even the entire body. In clinical terms, systemic manifestations usually present as generalized complaints including fever, malaise, myalgias, etc. In a minority, the manifestations can be more serious including, but not limited to, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), neurological deficits, spinal compression, thrombotic complications, etc. In this chapter, manifestations of various bacterial, tuberculous, viral, fungal and parasitic infections will be discussed. Bacterial infections usually cause localized infections involving a single organ such as pyogenic meningitis, community-acquired pneumonia, liver abscess, osteomyelitis, etc. (Fig. 2.7.1). However, in fulminant infections, as in bacterial endocarditis, portal pyaemia, etc., there can be multiple organ involvement, leading to severe morbidity and mortality. The clinical manifestations can be attributed to either the bacteria or its toxins. Systemic spread of infection can result from factors relating to the pathogen, host or environment. The bacterial pathogens which can cause a disseminated disease can be exogeneous or be a normal colonizing organism in the human body. The typical organisms which colonize the human body include Staphylococcus aureus in the skin, pneumococcus in the upper respiratory tract, coliforms and enterococci in the lower gastrointestinal tract, etc. When there is a breach of the surface or when there is increase in proliferation of the organisms, they can cause infection, which is usually localized (Fig. 2.7.2). However, depending upon the virulence of the organism, poor host immunity (Fig. 2.7.3) or favourable environmental factors for the pathogen, there can be deep penetration and dissemination, leading to bacteraemia, septicaemia, sepsis and septic shock. In metastatic spread, the organisms may spread to multiple organs and cause infection in the seeded organ. Common examples include Staphylococcus infection resulting in hospital-acquired pneumonia, osteomyelitis (Fig. 2.7.4), endocarditis; Staphylococcus epidermidis causing endocarditis and prosthetic joint infections; Streptococcus pyogenes causing streptococcal toxic shock syndrome; Streptococcus pneumoniae causing meningitis and pneumonia; enteric gram-negative bacilli causing urinary (Figs 2.7.5 and 2.7.6), hepatobiliary and intraabdominal infections. Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases and is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Although it principally involves the respiratory system, it can cause widespread disease and affect any part of the body (Fig. 2.7.7). The most common focus of extrapulmonary TB is the abdomen, affecting solid organs more commonly than the gastrointestinal tract. Pulmonary Manifestations of TB depend on whether the infection is primary or postprimary. Primary pulmonary TB is usually seen in children with characteristic radiological feature being that of ipsilateral hilar and paratracheal lymphadenopathy, usually right-sided. Postprimary pulmonary TB occurs as a result of reactivation in the setting of a decreased immune status (Fig. 2.7.8A and B). Patchy consolidation or poorly defined linear and nodular opacities are the most common features of postprimary TB. Cavitation, tuberculoma formation and miliary TB (Fig. 2.7.9) are other recognized forms of postprimary TB. Lymphadenopathy: Abdominal lymphadenopathy, being the most common manifestation of abdominal TB, characteristically results in mesenteric and peripancreatic lymph node group enlargement, with multiple groups affected simultaneously (Fig. 2.7.10). The enlarged lymph nodes show rim enhancement at CT, finding that is characteristic of, but not pathognomonic for caseous necrosis. These lymph node masses do not cause biliary, gastrointestinal or genitourinary obstruction. Central nervous system involvement: The central nervous system (CNS) is involved by haematogeneous spread of infection. Meningeal involvement: Both the leptomeninges and pachymeninges may be involved, the former being more common. Leptomeningeal TB presents as thick enhancing exudates involving the basal cisterns and adjacent subarachnoid spaces (Fig. 2.7.11). Complications include obstructive hydrocephalus (Fig. 2.7.12) and infracts secondary to vasculitis (Figs. 2.7.13 and 2.7.14). Involvement of the dura matter presents as plaque-like thickening of the dura usually at the skull base showing homogeneous contrast enhancement or calcifications (DD: meningioma, sarcoidosis, lymphoma). Parenchymal involvement may present as ring-enhancing lesions – granuloma (tuberculoma), abscesses and encephalitis (Fig. 2.7.15). Enhancement of the adjacent meninges may be seen. Peritoneal involvement: Peritoneal involvement in abdominal TB has been described under three subtypes: wet, fibrotic and dry. Wet type of peritonitis, being the most common (90% of cases), features large amounts of free or loculated ascites. The high protein content of the fluid leads to increased attenuation values (20–45 HU) relative to water at CT. The latter forms, the fibrotic-fixed type and the dry or plastic-type are less commonly seen. Gastrointestinal manifestations: Gastrointestinal TB is not very common. However, when it is observed, it primarily involves the ileocecal region (usually both the terminal ileum and the caecum). Ileocecal region involvement has been observed in as high as 90% of cases. One can observe that concentric wall thickening is the most common finding seen on CT scan (Fig. 2.7.16). In cases where such thickening is eccentric, by and large, the medial caecal wall tends to be involved. Enlargement of adjacent lymph nodes is also observed (Fig. 2.7.17). A widely gaping, thickened, patulous ileocecal valve with narrowed terminal ileum is characteristic of TB. Disseminated TB tends to involve the liver and spleen and is either micronodular-miliary or macronodular. Miliary hepatic involvement is characterized by multiple small nodules which may not be seen at CT. The liver appears hyperechoic on ultrasound. Macronodular hepatic TB, an uncommon variety, is characterized by irregular hypoattenuating lesions showing minimal central but definite peripheral contrast enhancement at CT. On MRI, the lesions are hypointense on T1WI, hyperintense on T2WI, minimally enhancing honeycomb-like lesions on T1 postcontrast images. On T2-weighted images, the lesions show less intense rim relative to the surrounding liver. However, hepatic tuberculomas eventually tend to calcify. Adrenal TB: Bilateral and asymmetric involvement of adrenals is common. The CT signs of active tuberculous adrenalitis are bilaterally enlarged glands associated with large, hypoattenuating necrotic areas, with or without dotlike calcification. The gland may undergo atrophy and calcification in the end stage of the disease. Genitourinary manifestations: Genitourinary TB is the most common way in which extrapulmonary TB manifests itself. Renal involvement: Unilateral involvement is seen in approximately 75% of renal TB, the most common CT finding being renal calcification (50% of cases) (Fig. 2.7.18). The earliest abnormality seen at intravenous urography is a “moth-eaten” calix due to erosions that can eventually progress to papillary necrosis. Hydronephrosis is often due to a stricture of the ureteropelvic junction. Other findings include renal parenchymal cavitation manifesting itself as irregular pools of contrast material and dilated calyces which are related to infundibular strictures at one or more sites within the collecting system. Lobar pattern of calcifications is seen in end-stage TB. End-stage fibrosis and subsequent obstructive uropathy produce autonephrectomy. Ureter and urinary bladder involvement: TB most commonly involves distal one-third of the ureter, characterized by a thickened ureteric wall and strictures. Complications include hydronephrosis and hydroureter of varying degrees, usually due to obstruction at the vesicoureteric junction secondary to tuberculous cystitis and ureteritis, but possibly due to reflux. Reduced urinary bladder capacity is the most common finding in tuberculous cystitis. In advanced disease, small, irregular and calcified bladder is seen due to scarring. Genital TB: Genital TB has a strong predilection for fallopian tubes in women causing bilateral salpingitis. Findings which are seen at hysterosalpingography include obstruction and multiple constrictions of the fallopian tubes and endometrial adhesions causing deformity of the cavity. A tuboovarian abscess extending through the peritoneum into the extraperitoneal compartment strongly favours TB (Fig. 2.7.19). Irregular hypoechoic areas in the peripheral zone of the prostate are the most common finding seen at transrectal ultrasonography in tuberculous prostatitis. Epididymis and prostate are commonly involved in males. Contrast-enhanced CT shows hypoattenuating prostatic lesions, which likely represent foci of caseous necrosis and inflammation. Nontuberculous pyogenic prostatic abscesses have a similar CT appearance. Tuberculous epididymitis or epididymoorchitis has nonspecific imaging findings. Syphilis is a chronic systemic disease caused by a gram-negative spirochete – treponema pallidum. The disease shows a waxing and waning course with periods of latency. The main mode of transmission is through sexual contact – mucocutaneous surfaces. Transplacental transmission is noted from the mother to the offspring. Three stages of syphilis have been described depending on the time since infection. Primary syphilis is characterized by local disease manifestations of ulceration and chancroid formation. Secondary syphilis results from bacteraemia with systemic manifestations. Tertiary syphilis represents the latent stage of the disease with periods of relapse, which can spread over years. Congenital syphilis results from transplacental transmission of the disease. It is divided into early and late stages based on the appearance of the symptoms (before or after 2 years of age). Fungal infections can disseminate to any body compartment, visceral organ or tissue, including the gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary and genitourinary systems. Involvement of the paranasal sinuses is commonly seen with mucormycosis with possible spread of infection to the brain (Fig. 2.7.21). Fungal infections of the lung may show a myriad of manifestations depending on the immune status of the patient. The most common manifestation is large parenchymal nodules (Fig. 2.7.22) which may or may not cavitate. Infection of preformed cavities by aspergillus results in fungal ball or mycetoma (Fig. 2.7.23). With waning immunity, the infection may progress to semiinvasive or invasive forms (Fig. 2.7.24). Mediastinal lymph adenopathy is a common finding (Fig. 2.7.25). Involvement of ribs and bony cage can occur with adjacent soft-tissue abscess (Fig. 2.7.26).

2.7: Systemic manifestations of infection/infestation

Introduction

Bacterial infections

Tuberculosis

Systemic manifestations of tuberculosis

Syphilis

Radiological features

Radiological features in adults

Fungal diseases: Candidiasis, Aspergillosis, Mucor, Madura-mycosis, etc.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree