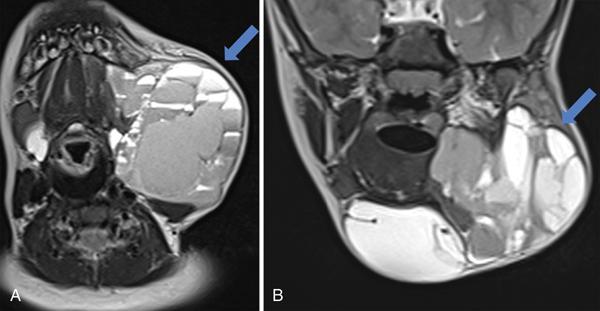

Seetharaman C, Gayathri Priyadharshinee, R Gopinath, S.P. Rajesh LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY POINTS Skin and subcutaneous lesions are commonly seen in routine clinical practice as well as incidentally detected during imaging studies done for other clinical indications. These lesions pose a challenge for the radiologists, and the awareness of classical imaging findings allows them to confidently diagnose the lesion. Benign lesions of the skin and subcutaneous region are far more common than malignant lesions. Ultrasound is usually the first imaging modality used to assess superficial soft-tissue lesions. CT and MRI can be helpful for the radiologist to differentiate various skin lesions and malignancies. Finally, some lesions will always require excision for histological confirmation. The skin is the largest anatomic organ of the human body, accounting for about 12–15% of total body weight, and covers 1.5–2 m2 of surface area and with a thickness of about 0.5–4 mm. The skin is made of three layers, namely, epidermis, dermis and subcutis. The skin acts as a protective barrier between the visceral body and environment. Skin plays important role in immunity, temperature regulation, sensation and vitamin D synthesis. The epidermis is the outermost layer of skin and is composed of five sublayers. The most superficial layer is stratum corneum, followed by stratum lucidum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum and stratum basale being the deepest layer. The mitotic activity of keratinocytes is seen in basal cell layer, which move up the strata changing shape and composition as they differentiate and become filled with keratin. The dermis is primarily composed of connective tissue and lies between epidermis and subcutis layers of the skin. This layer contains many nerve endings, hair follicles, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, lymphatic vessels and blood vessels. The deepest layer of skin is subcutis (subcutaneous tissue), which is primarily composed of adipose tissue. This serves to attach the skin to underlying bone and muscle and supplying it with blood vessels and nerves. In current scenario, the available radiological imaging techniques for assessing skin and superficial lesions include high-frequency ultrasound, CT, MRI and 18F-FDG-PET. Out of these, HR-US is routinely used as the first imaging modality. CT and MRI are used for further characterization of the lesions and in evaluation of the locoregional extent of the disease. CT, MRI and PET/CT are commonly used for staging, preoperative planning and posttreatment assessment of skin and subcutaneous malignancies. Improvement and recent advances in sonography have increased the scope of its applications in evaluation of soft tissue as well as overlying skin and subcutaneous layers. In the literature, increased usage of high resolution of ultrasound to assess skin and related pathologies is evident. Ultrasound has got several advantages for studying the skin and soft tissue. It permits optimal penetration/resolution balance in evaluation of skin and soft-tissue abnormalities using different frequencies and probes. Other advantages include cost-effectiveness, noninvasiveness, repeatability, lack of radiation, guidance for biopsy and shorter imaging times. Ultrasound evaluation with multichannel colour Doppler machines and variable-frequency probes (15 MHz or higher) is suggested for an optimal examination since definition of skin layers is better visualized at higher frequencies. Extended field of view and compound reconstruction software can improve the imaging quality. Usually, sonography studies for skin and superficial lesions give the best results when done without any compression of the lesion and applying adequate gel to focus on most superficial layers. Sedation is reserved for younger children who do not cooperate (Table 3.43.1). A. Mandava, P.R. Ravuri, R. Konathan. High-resolution ultrasound imaging of cutaneous lesions. Ind. J. Radiol. Imag. 23 (2013) 269–277. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.120272. The skin is composed of three layers: epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The echogenicity of the skin layers primarily depends on its main components. Echogenicity of epidermis is influenced by the presence of keratin, the dermis by its content of collagen and the subcutaneous tissue by the amount of fat lobules. Normally, the epidermis appears as a hyperechoic line in all places except palmar and plantar regions where it appears as bilaminar hyperechoic parallel lines. The dermis appears as a hyperechoic band, but less bright than the epidermis. The subcutaneous tissue appears as a hypoechoic fatty layer with hyperechoic fibrous septa separating fat lobules. Deeper to this level, the superficial fascia covering muscles is seen as a hyperechoic regular line. The latest advances in CT have revolutionized imaging with current CT scanners giving a spatial resolution of about 0.5–0.625 mm. With drastic reduction of acquisition time in current CT scanners, CT of the neck and chest producing images of diagnostic quality can be obtained even in patients with breathlessness within few seconds. CT is useful to detect calcifications in skin and soft-tissue lesions and bone erosions caused by the lesions which could give valuable insight about the pathology. It is also useful in evaluating the deeper and lateral extent of the lesion. Axial and reconstructed coronal and sagittal images are useful in studying specific details of skin and superficial soft-tissue lesions, its relation to surrounding structures, features of invasion and mass effect. Contrast-enhanced CT helps to analyze vascular structures, to study enhancement pattern of lesions and for performing CT angiography. Various 3D reconstruction techniques such as 3D shaded surface display (SSD), multiplanar volume reconstruction (MPVR) and volume-rendering (VR) techniques aid in improving diagnosis. Because of its longer acquisition time and associated artefacts, MRI was not preferred in the initial days. However, with the newer advanced short acquisition time sequences and small surface coils, MRI is increasingly being used in the imaging of skin and superficial pathologies. Microscopy coil MRI offers detailed information about the deeper extent of skin and superficial soft-tissue tumours, which is not apparent in clinical inspection or in other imaging modalities. With its inherent soft-tissue characterization, it scores over CT in local staging of tumours. These details help the clinician to analyze about the lesion resectability and derive at an optimal surgical approach. Microscopy coil MRI is appropriate only for imaging superficial structures and is useful in evaluation skin and superficial lesions. The surface coils are receive-only radiofrequency coil used in MRI. Surface coils are small with smaller field of view and can be placed near the part of anatomy being imaged. They have good signal-to-noise ratio and allows smaller voxel size and high image resolution. This allows evaluation of skin lesions as small as 300 µm. MRI sequences can be acquired in any desired plane and is best planned to depict the depth of tumour penetration. The most important information required for surgical planning include depth of the lesion infiltration and the spatial relationships between lesion and underlying anatomic structures. The epidermis appears as thin superficial layer of increased signal intensity and is better demonstrated in 3T than 1.5T MRI. The dermis and subcutis could be delineated separately, which helps in identifying deeper infiltration of epidermal lesions. The dermis shows intermediate signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images and is superficial to the hyperintense adipose tissue within the subcutis. FDG-PET imaging provides morphologic and functional information about the tumours. PET-CT is usually reserved for cases to delineate between malignant and nonmalignant aetiologies, staging of skin and superficial soft-tissue malignancies and response assessment of treatment. It can also reveal subtle recurrences, micrometastases and indeterminate nodal metastases, resulting from various skin malignancies (Table 3.43.2). Lipoma is the most frequently encountered subcutaneous mass. These are benign neoplasms arising from mature adipocytes with surrounding and intervening connective tissue stroma. They most commonly occur in the head and neck region with posterior neck predominance. Almost 80% of lipomas occur in adults. On ultrasound, lipomas appear typically oval, soft, variably echogenic masses which are compressible with no or minimal demonstrable internal vascularity. Fine echogenic bands run parallel to the skin surface. On cross-sectional imaging, the lesions follow fat density/signal on all sequences and are nonenhancing. Any atypical features such as prominent T2 hyperintensity, irregular enhancing septa and nodular enhancement should raise the suspicion towards atypical lipomatous tumour or malignant transformation. Infantile haemangioma. Infantile haemangiomas are benign vascular neoplasms and are the most common head and neck tumours of infancy. These lesions are small or absent at birth, increase in size in first year of life and show progressive involution during early childhood. Infantile haemangiomas are predominantly superficial soft-tissue lesions. On ultrasound, they appear as well-defined echogenic mass with prominent internal vascularity. MRI shows T2 hyperintense lesion with intense and homogeneous contrast enhancement. Congenital haemangioma. These lesions are commonly seen at birth and are benign vascular tumours. They may present as soft-tissue mass, in the viscera or as extraaxial lesions in intracranial regions. The lesions are classified as rapidly involuting, noninvoluting and partially involuting based on their behaviour over time. Usually, they are not easily differentiated from infantile haemangioma on imaging but will have specific histological and presenting features. Extensive flat facial lesions can be associated with a variety of intracranial anomalies, and MRI should be considered. Arteriovenous/venous malformation. They can be either high-flow or low-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). High-flow AVMs are formed due to abnormal connections between arteries and veins with absence of intervening normal capillary bed. Ultrasound will show both abnormal arterial and venous flow. Identification of feeding arterial supply can guide therapy. MRI will show multiple flow voids. Low-flow venous malformations (VMs) consist of dysplastic venous channels without arteriovenous shunting. Spectral ultrasound shows low flow in enlarged vascular channels. Phleboliths within a vascular anomaly are characteristic for VMs. Lymphatic malformation. Lymphatic malformations (LMs) are cystic masses of dysplastic lymphatic channels filled with protein-rich fluid. They are generally present from birth but may be asymptomatic until complicated by infection or hemorrhage. Large LMs may exert considerable mass effect, potentially endangering the airway and causing bony remodelling of the facial skeleton. MRI is the investigation of choice to confirm the diagnosis and delineate the extent of LMs, which characteristically appear as complex cystic lesions with fluid–fluid levels. The signal intensity of the fluid–fluid levels depends on the haemorrhage and protein content. Different cystic locules can be seen in separate fascial planes. Combined malformation. Various combinations of capillary, venous, lymphatic and arteriovenous malformations can also be seen in the head and neck region. The imaging findings reflect the various malformations present in the lesion. MRI is the modality of choice for evaluation of the vascular neoplasms and vascular malformations, its spatial and transspatial extensions, complications and treatment planning (Fig. 3.43.1).

3.43: Superficial and trans spatial lesions

Abbreviations

Skin and superficial soft-tissue pathologies

Introduction

Anatomy of skin

Imaging modalities

High-resolution ultrasound

Imaging considerations.

Sl. No.

Frequency of Ultrasound (in MHz)

Approximate Depth of Penetration (cm)

Structures

1

7.5

>4.0

Subcutis and lymph nodes

2

13.5–50

3.0–0.3

Epidermis and dermis

3

20

0.6–0.7

Epidermis and dermis

4

50–100

0.3–0.015

Epidermis only

Normal sonographic anatomy of skin.

Computed tomography

Magnetic imaging resonance

Imaging considerations.

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography

Mesenchymal pathologies (Table 3.43.3)

Common mesenchymal tumours

Lipoma

Diagnosis

Age

Plane

Comments

Lipoma

Adults

Subcutaneous

Follows fat echoes/density/signal intensity.

Hibernoma

Young adults/adults

Subcutaneous

Soft tissue lesion arising from remnants of foetal brown fat. Incomplete suppression in fat suppressed MRI sequence.

Fibromatosis

Adults

Fascial/Subcutaneous

Usually, hypointense in T1 and T2 images.

Vascular tumours and malformations

All ages

Cutaneous, subcutaneous and transspatial

Vascular masses with abnormal flow/complex cystic masses with fluid–fluid levels.

Peripheral nerve sheath tumour (schwannoma, neurofibroma), traumatic neuroma, palisaded encapsulated neuroma, diffuse cutaneous neurofibroma

Adults

Cutaneous, subcutaneous

Neurofibroma is usually associated with NF1; malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour is rare.

Liposarcoma

Adults

Cutaneous (rare), subcutaneous

Usually in extremities, retroperitoneum; tumours that are more differentiated contain more fat and less soft tissue.

Nodular fasciitis

Adults

Fascial

Benign rapidly growing nonneoplastic fibrous lesion with fascial tail.

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

Adults

Subcutaneous/soft tissue

Enhancing solid lesions with prominent areas of necrosis, haemorrhage and calcifications.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Adults

Cutaneous

Protuberant mass with skin involvement and fascial tail in most of the masses

Vascular tumours and vascular malformations

Common vascular lesions and malformations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree