Route of surgery

Uterine/fibroid size

Number

Position

Abdominal

Any

Any

Any

Laparoscopic

≤15 cm total fibroid diameter

≤3

Subserous/intramural

Hysteroscopic

≤5 diameter

1 to a few

Intracavitary/submucous

Vaginal

≤14 weeks uterine size

1 to several

Vaginal/intracavitary/intramural/subserous

The choice of which type of myomectomy to carry out is obvious in some cases, while in others it is a matter of the experience and preference of the gynaecologist. At one end of the spectrum, women with gross uterine enlargement secondary to multiple large fibroids have little option but to undergo open myomectomy. At the other extreme, there would be few who would disagree that hysteroscopic myomectomy for one or two small submucous fibroids is the best and most elegant technique in such cases, while laparoscopic myomectomy is most suited to women who have a few small to medium-sized subserous/intramural fibroids.

As is typical of all surgical procedures, individual surgical practice is not quite as clear cut. For instance, there are a handful of enthusiasts who carry out laparoscopic myomectomy in cases where, because of the size and number of fibroids to be removed, the majority of gynaecologists would not even consider it (Sinha et al. 2008). Another example is vaginal myomectomy, a technique which has been all but forgotten by the majority of gynaecologists; we consider that this technique has several important advantages over the other route of surgery, so offer it to suitable patients as a matter of routine as demonstrated in Fig. 1 (Thomas and Magos 2011).

Fig. 1

Myomectomies carried out under the care of the senior author (2005–2011)

4 Open Myomectomy

Open myomectomy is the traditional conservative procedure when the uterus is significantly enlarged by multiple, large fibroids (Breech and Rock 2008). While the advent of pelvic ultrasound scanning has meant that women are diagnosed with relatively small fibroids at an earlier age than previously, and indeed in many cases uterine fibroids are an incidental finding when imaging is done for some other reason, it is still the case that a significant proportion of patients who present to gynaecologists with a diagnosis of uterine fibroids and symptoms have an easily palpable pelvic mass in the abdomen. In the majority of such cases, open myomectomy is both the most appropriate and most thorough treatment if uterine function is to be preserved. About 40,000 open myomectomies are done each year in the USA, and 2,000 or so in England.

Having decided to carry out an open myomectomy, the next decision is whether or not to delay surgery and pre-treat with a GnRH analogue. Pre-treatment for 3 months is certainly popular for a number of reasons: there is a good chance that therapy will inhibit menstruation which may well have been abnormally heavy previously; amenorrhoea should lead to improved haemoglobin with correction any pre-existing anaemia, particularly if combined with iron therapy; it should reduce fibroid and uterine size, thereby allowing for a smaller laparotomy incision and possibly the use of a cosmetically and functionally superior low transverse laparotomy incision rather than a vertical one.

There are, however, disadvantages to GnRH pre-treatment. Quite apart from the need to delay surgery for the analogues to take effect, treatment is expensive and associated with menopausal side-effects such as hot flushes and night sweats (although this can be counteracted by concurrent oestrogen add-back therapy). Dissecting the fibroids from the myometrium tends to be more difficult as the tissue planes are often less distinct. There may be little or no benefit in terms of operative blood loss. Perhaps most importantly, there is good evidence that there is a higher fibroid recurrence rate in patients who have been pre-treated for the simple fact that small fibroids become so small with therapy that they are missed during surgery (Vercellini et al. 2003).

In consideration of the above, our protocol is to only prescribe GnRH analogue pre-treatment as an adjunct to correcting anaemia due to menorrhagia, and if shrinking the uterus will avoid the need for a vertical laparotomy incision. It may be that the recently introduced orally active selective progesterone receptor modulator, ulipristal acetate, may prove to be a more acceptable option to stop menstruation and shrink fibroids prior to surgery.

4.1 Patient Selection

Any patient is suitable for open myomectomy, but in reality, women who are offered this type of intervention are the ones who are judged to be unsuitable for the other approaches. This usually means that the typical woman who undergoes open myomectomy has multiple large fibroids, often extending to or above the umbilicus. Occasionally, open myomectomy is done on patients with relatively small or few fibroids when it tends to be a matter of patient preference. It is certainly true that, for instance, open myomectomy has more of a chance of removing all the fibroids with a stronger uterine repair for subsequent child-bearing than laparoscopic myomectomy, and for some this is an important consideration.

4.2 Surgical Technique

The default incision for open myomectomy is a low transverse (Pfannenstiel) laparotomy. In some cases this is inappropriate because of the size of the fibroids, the presence of a previous midline incision or concern about adhesions, when a vertical laparotomy may be preferred. Quite apart from the cosmetic disadvantage of a vertical laparotomy, this incision has a considerably greater risk of breakdown and post-operative herniation. At the other end of the scale when there are relatively few, small fibroids to remove, surgery can be done via a mini-laparotomy (incision ≤7 cm) and even ultraminilaparotomy (incision ≤4 cm) as an alternative to laparoscopic myomectomy.

The aim of surgery is to remove as many of the fibroids as possible, ideally all of them, no matter how small. Rather than incising the uterus over each and every fibroid, the recommended technique is (a) to remove the fibroids through as few incisions as possible, and (b) to avoid posterior uterine incisions to reduce the chance of post-operative adhesions involving the fallopian tubes and ovaries risking subfertility (Breech and Rock 2008). It is for this reason that most procedures start with a single vertical anterior midline incision, and if a posterior incision is required, we prefer a “hood incision”, originally described by Victor Bonney, arguably the most important figure in popularising open myomectomy in the UK (Chamberlain 2003).

Whatever the approach, we prefer to only open the endometrial cavity if this is unavoidable because of the presence of intracavitary or submucous fibroids. There are those, however, who advocate removing even posterior fibroids through an anterior uterine incision by cutting through the uterine cavity. Traditionally, if the uterine cavity has been opened at open myomectomy, any subsequent deliveries are done by elective Caesarean section.

The major risk of open myomectomy is haemorrhage, which if severe may necessitate the greatest fear not only for the patient but the gynaecologist, namely hysterectomy. Various strategies, both pre- and intra-operative, have been advocated to reduce this risk (Table 2). Radiologists, of course, know the history of uterine artery embolisation (UAE) and are aware that UAE was originally introduced not as a definitive management, but as a precursor to open myomectomy to reduce the risk of intra-operative haemorrhage (Ravina et al. 1994).

Table 2

Techniques which have been tried to reduce intra-operative blood loss at open myomectomy

Pre-operative techniques GnRHa Uterine artery embolisation |

Intra-operative techniques Hypotensive anaesthesia Single midline uterine incision Enucleation of coagulation cascade (e.g. tranexamic acid, aprotinin, aminocaproic acid, recombinant factor VIIa, gelatin-thrombin sealant) Dissection techniques (e.g. laser electrosurgery chemical dissection with sodium-2-mercaptoethane sulfonate [MESNA]) Uterotonics (e.g. ergometrine, oxytocin, misoprostol, sulprostone) Hormonal tourniquet (e.g. vasopressin, terlipressin, epinephrine, bupivacaine + adrenaline) Mechanical tourniquet (e.g. clamps, clips, electrocoagulation, single tourniquet, triple tourniquets) |

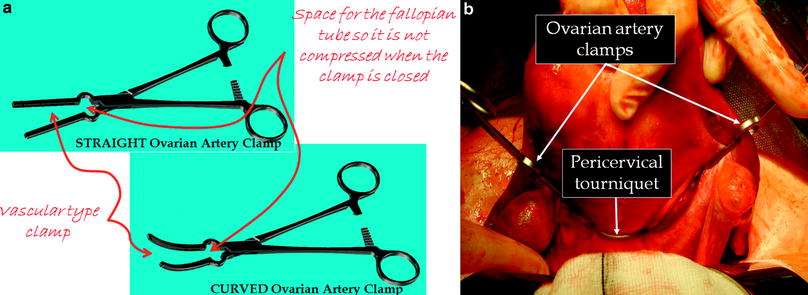

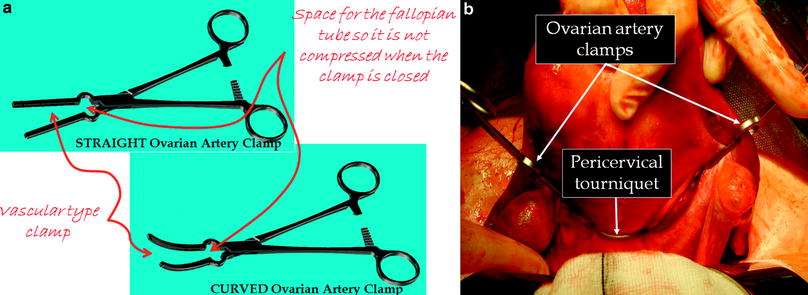

Despite the long history of the operation, only a few of these strategies have been proven to be effective under controlled conditions. Table 3 summarises the results of randomized trials of various intra-operative techniques which have been studied, showing that the most effective strategy is the use of triple tourniquets to occlude uterine perfusion during surgery (Kongnyuy and Wiysonge 2011). The classic technique is to place tourniquets around the cervix and each infundibulopelvic ligament to occlude the uterine and ovarian arteries thereby rendering the uterus totally avascular during surgery (Breech and Rock 2008). Concern about prolonged ovarian hypoxia has meant that some gynaecologists release the ovarian tourniquets every 20 min or so, but this of course adds to the blood loss. To circumvent this problem, we have designed a special clamp (Ovarian Artery Clamp) which can be applied medial to the ovaries to occlude the ovarian blood supply to the uterus without crushing the fallopian tubes as would be the case with a standard clamp (Fig. 2a, b) (Magos et al. 2011). Preliminary results from our Institution show that this technique is as effective as conventional triple tourniquets.

Table 3

Efficacy of various intra-operative techniques to reduce bleeding at open myomectomy

12 randomized studies 674 women |

Not effective Intravenous oxytocin Myoma enucleation by morcellation |

Effective Intramyometrial bupivacaine + adrenaline (MD-69 ml) Intravaginal misoprostol (MD-149 ml) Single tourniquet (MD-241 ml) Intravenous tranexamic acid (MD-243 ml) Intramyometrial vasopressin (MD-299 ml) Gelatin-thrombin matrix (MD-545 ml) Triple tourniquets (MD-1870 ml) |

Fig. 2

a Straight and curved ovarian artery clamps for use at open myomectomy. b Pericervical tourniquet and ovarian artery clamps in position at the start of open myomectomy

As a further refinement of the technique, and a reflection of the fact that it can be difficult to apply an effective tourniquet around the cervix, we have reported the use of sterilised cable ties as an alternative to catheters and sutures (Al-Shabibi et al. 2010). Interestingly, the use of cable ties at surgery can be traced back to the 1970s!

On completion of the myomectomy, it is generally recommended that steps should be taken to reduce the risk of post-operative adhesions. A variety of anti-adhesive agents can be used for this, although in reality, their efficacy remains largely unproven (Ahmad et al. 2008). It is our usual practice to leave a drain in the pelvis both to monitor any oozing from the uterus and reduce the chance of a clinically significant post-operative haematoma. We also give prophylactic antibiotics during and after the surgery. Prophylactic anticoagulants are not given pre-operatively for fear that this will increase the risk of intra-operative haemorrhage, and instead we rely on anti-embolism compression stockings and pneumatic calf pumps during surgery to reduce the chance of deep vein thrombosis.

Drains and bladder catheters are usually removed after 2 days, and although variable, most patients are discharged from hospital after 5–6 days.

4.3 Operative Complications

Intra- and to some extent post-operative haemorrhage is the main risk of surgery. As noted above, triple tourniquets are a very effective technique for reducing bleeding complications, but even then around 10 % of our patients require a peri-operative blood transfusion (Taylor et al. 2005b; Al-Shabibi et al. 2009). Some may feel this rate of transfusion is unduly high, but the need for blood products very much depends on the size and number of fibroids removed. On average, we excise 15–20 fibroids per patient, a figure which is considerably more than reported in most published series (Hanstede et al. 2008).

Despite the extent of the surgery, we have never had to resort to hysterectomy because of intra- or post-operative bleeding. For instance, during the period 2005–2012, we only had to carry out two hysterectomies out of over 250 procedures, the indications for both being severe uterine sepsis following repeat open myomectomy; in one case, over 100 fibroids were removed at surgery. This compares with rates of hysterectomy because of bleeding of 4 % in other published series (Olufowobi et al. 2004).

The other typical complications (e.g. wound, urinary tract and chest infections, venous thrombosis), occur as with any other open pelvic surgery. All patients are counseled regarding the theoretical risk of injury to bowel and bladder, but in reality, this rarely happens unless there are extensive adhesions around the uterus. We advise all our patients undergoing open myomectomy to delay trying for a pregnancy for at least 6 months to give time for the uterus to heal.

5 Hysteroscopic Myomectomy

To a gynaecologist, hysteroscopic myomectomy is the total opposite to open myomectomy. Whereas open myomectomy clearly represents major surgery with all its associated risks including haemorrhage, hysteroscopic myomectomy is an elegant and above all, relatively quick and atraumatic treatment for intracavitary and submucous fibroids. Bleeding is rarely an issue.

First described by the American Robert Neuwirth in 1976, when he used hysteroscopic scissors to cut the stalk of pedunculated intra-cavitary fibroids, two years later he introduced what arguably remains one of the most important development in modern gynaecology, the use of the resectoscope for excising submucous fibroids which are partially embedded in the myometrium (Neuwirth and Amin 1976; Neuwirth 1978). This includes most submucous myomas.

The instrumentation and techniques for hysteroscopic myomectomy have been developed further in the ensuing years with the introduction of the Versapoint device and more recently the intra-uterine morcellator (Di Spiezio et al. 2008). However, few would argue that the resectoscope remains the instrument par excellence for hysteroscopic myomectomy. It is both the most efficient instrument and the only one which can be used to remove fibroids which extend deep into the myometrium. The introduction of the miniresectoscope, a paediatric instrument which has been lengthened to make it suitable for use in adults, has meant that the benefits of resectoscopic surgery is now available in the outpatient/office setting (Papalampros et al. 2009).

5.1 Patient Selection

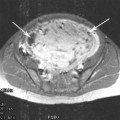

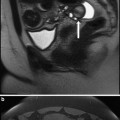

Whatever the instrumentation, patient selection is of paramount importance (Table 1). Hysteroscopic myomectomy should only be offered to women who have one or two relatively small (≤5 cm for most gynaecologists) submucous fibroids (Fig. 3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree