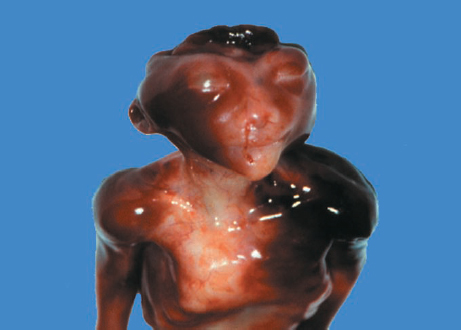

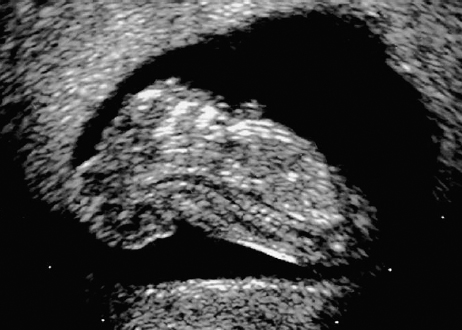

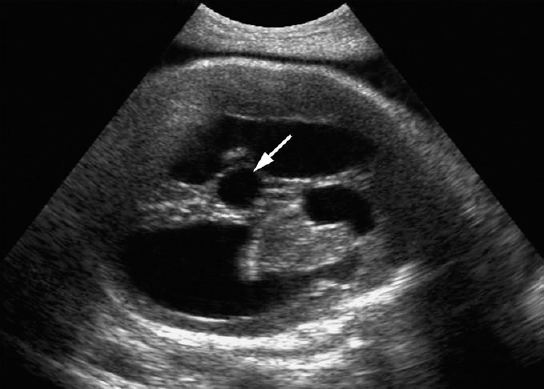

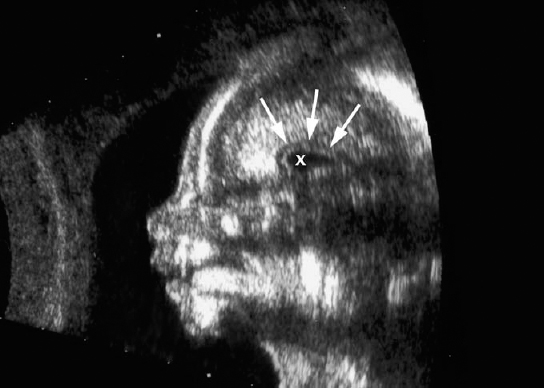

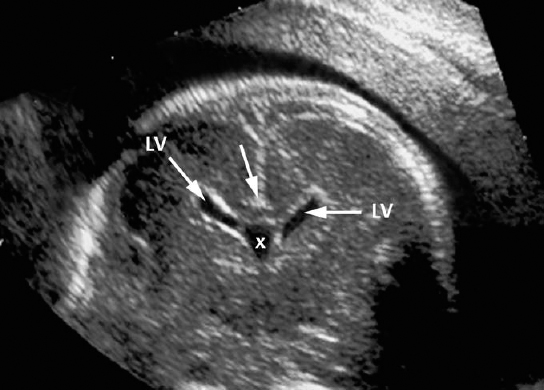

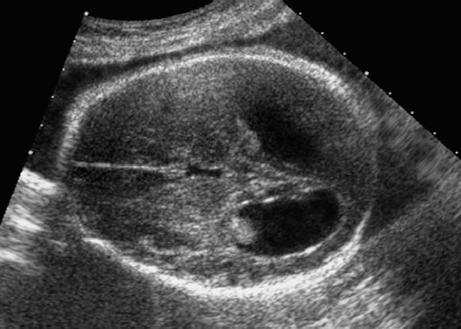

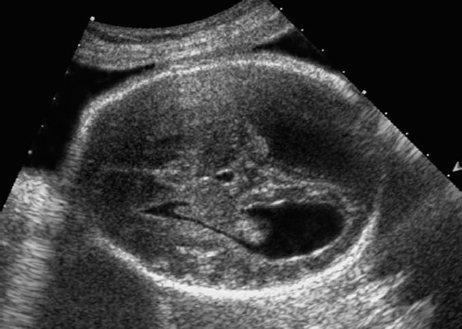

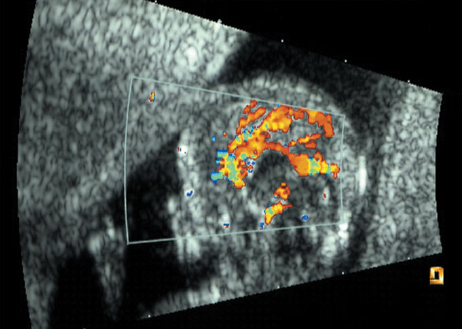

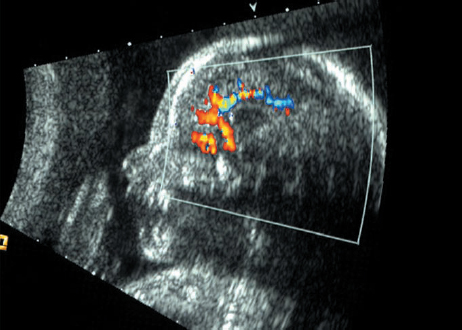

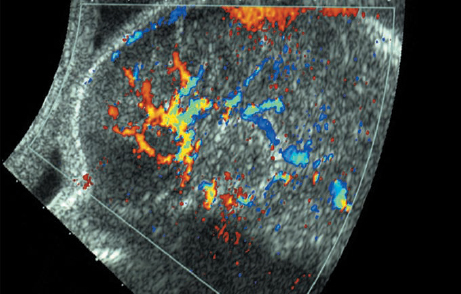

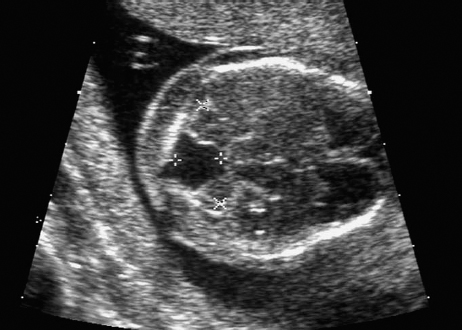

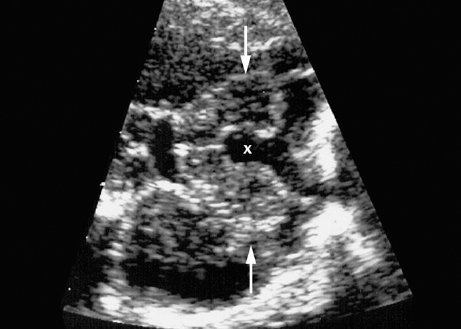

Definition: Anencephaly, and in particular the exencephaly–anencephaly sequence, belongs to the group of cranial neural tube defects and is a condition in which the cranial vault, overlying skin, the meninges and brain are absent. Incidence: Geographical differences are marked; in Germany and the United States, the figure is one in 1000, while in certain parts of the United Kingdom it is as high as one in 100 births. Sex ratio: M: F = 1.0:3.7 Clinical history/genetics: Family history of neural tube defect; multifactorial transmission, with varying penetrance and influence of environmental factors, is assumed. Risk of recurrence 2–3%. In certain cases, X-chromosomal transmission has also been described. Teratogens: Valproic acid, folic acid antagonists, diabetes mellitus, hyperthermia, folic acid deficiency. Embryology: The neural tube closes between the 20th and 28th day after conception. In case of anencephaly, the cranial vault is absent. The developing brain seen in the early embryonic stage degenerates as the pregnancy progresses—mainly in the second trimester, apparently due to unprotected contact with the amniotic fluid. Associated malformations: Spina bifida, facial clefts, omphalocele, renal anomalies, amniotic banding, Cantrell pentalogy. Ultrasound findings: The cranial vault, usually fully formed at 9 weeks of pregnancy, is absent. At 9–11 weeks, the cerebrovascular area can be identified, but this degenerates up to 15 weeks. Basal vessels may even be seen later. Even at the end of first trimester, the form of the head appears unusual, and the cerebrovascular area and in particular the brain float freely, as seen on vaginal sonography. Biometric assessment at the beginning of the second trimester fails to demonstrate the biparietal diameter, thus confirming the diagnosis. The lower part of the facial vault up to the level of the orbits is not affected, and even the brain stem remains intact. The fetal face often has a “frog-like” appearance, with prominent orbits. Myelomeningocele in the cervical or lumbosacral region may accompany this anomaly. In late pregnancy, the absence of a swallowing reflex leads to hydramnios. Fig. 2.1 Exencephaly. Floating brain in the absence of the cranial vault. Exencephaly, 16 + 6 weeks. Fig. 2.3 Anencephaly. Ultrasound showing the frontal view. The lenses of the eye are well recognized above the orbits, where the bony skull ends (“frog head”). Fig. 2.4 Anencephaly. Frontal view, showing the fetus after termination of pregnancy. Fig. 2.5 Anencephaly. Ultrasound view in the sagittal plane. Fig. 2.6 Anencephaly. Sagittal view of the fetus after termination of pregnancy. Fig. 2.7 Exencephaly—anencephaly sequence. 12 weeks. The cranial vault has not been formed. The brain tissue is floating in the amniotic fluid above the base of the skull. Procedure after birth: Therapy is not possible. Some of the affected neonates survive as much as a few days after birth. Prognosis: This is considered to be a fatal malformation, resulting in intrauterine death in 50% of the affected fetuses, with the remaining 50% dying at the neonatal stage. Recommendation for the patient: Before planning the next pregnancy, a regular daily intake of folic acid (4mg/d) considerably reduces the risk of recurrence. Self-Help Organization Title: Anencephaly Support Foundation Description: Provides support for parents who are continuing a pregnancy after being diagnosed with an anencephalic infant. Information and resources for parents and professionals. Phone support, pen pals, literature, pictures. Scope: International network Founded: 1992 Address: 20311 Sienna Pines Court, Spring, TX 77379, United States Telephone: 1–888–206–7526 E-mail: asf@asfhelp.com References Anon. Prevalence of neural tube defects in 20 regions of Europe and the impact of prenatal diagnosis, 1980-1986. EUROCAT Working Group. J Epidemiol Community Health 1991; 45: 52–8. Becker R, Mende B, Stiemer B, Entezami M. Sonographic markers of exencephaly–anencephaly sequence at 9 + 3 gestational weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000; 16: 582–4. Boyd PA, Wellesley DG, De Walle HE et al. Evaluation of the prenatal diagnosis of neural tube defects by fetal ultrasonographic examination in different centres across Europe. J Med Screen 2000; 7:169–74. Cuiller F. [Prenatal diagnosis of exencephaly at 10 weeks’ gestation confirmed at 13 weeks gestation; in French.] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2001; 30: 706–7. Drugan A, Weissman A, Evans MI. Screening for neural tube defects. Clin Perinatol 2001; 28: 279–87. Goldstein RB, Filly RA, Callen PW. Sonography of anencephaly: pitfalls in early diagnosis. JCU J Clin Ultrasound 1989; 17: 397–402. Hardt W, Entezami M, Vogel M, Becker R. Die fetale Exenzephalie—Vorstadium der Anenzephalie? Ein kasuistischer Beitrag. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1999; 59: 135–8. Wilkins HL, Freedman W. Progression of exencephaly to anencephaly in the human fetus: an ultrasound perspective. Prenat Diagn 1991; 11: 227–33. Worthen NJ, Lawrence D, Bustillo M. Amniotic band syndrome: antepartum ultrasonic diagnosis of discordant anencephaly. JCU J Clin Ultrasound 1980; 8: 453–455. Definition: Displacement or congenital malformation of the aqueduct of Sylvius resulting in a congenital obstructive hydrocephalus. Incidence: One in 2000 births. Sex ratio: M : F = 1.8:1 Clinical history/genetics: Most cases are sporadic; 2–5% of hydrocephalus cases unrelated to a neural tube defect are inherited recessively through an X-chromosome-linked gene. The cause seems to be mutations of the L1 CAM gene (gene locus Xq28). Teratogens: Congenital infections (cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis). Embryology: The sylvian aqueduct connects the third and fourth ventricles and develops in the 6th week after conception. In 50% of cases, local infection such as gliosis can be detected histologically. Associated malformations: In X-linked aqueduct stenosis, 20% of the affected boys show deformities of the thumb. Additional malformations are present in 16% of cases. However, in cases of obstructive hydrocephalus, associated malformations are seen in 80%. Ultrasound findings: The third ventricle and lateral ventricles are widened, but not the fourth ventricle. The cerebellum and cisterna magna are normal, except in severely affected cases. Measurement of the remaining cortex does not allow accurate prediction of the prognosis, the rim of cortex being thinnest in the occipital region. Obstructive hydrocephalus may also develop in the third trimester of pregnancy. Obstructive hydrocephalus does not always cause enlargement of the head, so that intrauterine head circumference measurements are not predictive. Clinical management: Karyotyping procedure, possibly molecular-genetic diagnosis, and screening for intrauterine infections (TORCH). Intrauterine interventions such as placement of ventriculoamniotic shunt were attempted in the 1980 s, without adequate benefits. Regular sonographic assessments every 2–3 weeks as hydrocephalus may increase considerably. After 30 weeks of gestation, the benefit of early delivery and placement of a shunt has to be weighed up against the possible risks of a premature birth. In case of cephalic presentation and normal head circumference, cesarean section does not offer any advantage over vaginal delivery. Procedure after birth: The postnatal management depends on the presence of associated anomalies. The placement of ventriculoperitoneal or ventriculoatrial shunts will depend on the enlarging head circumference and the protein content of the cerebrospinal fluid. Shunts have to be replaced frequently in repeated operations, due to obstruction or as the child grows. Fenestration of the third ventricle into the basal cisterns is an alternative to shunt therapy. Prognosis: The neonatal mortality is in the range of 10–30%, depending on the accompanying malformations. Only 10% of survivors have an intelligence quotient (IQ) of over 70. References See section 2.9 (hydrocephalus). Definition: Echo-free structures arising from the arachnoid and located intracranially or in the spinal cord. Incidence: Rare. Clinical history/genetics: Mostly sporadic. Isolated cysts have been described, with auto-somal-recessive inheritance. Teratogens: Congenital infections. Embryology: The etiology of congenital arachnoid cysts is uncertain. Maldevelopment of the leptomeninges may be responsible. After birth, these cysts may be acquired through infection or trauma. Associated malformations: Obstructive hydrocephalus due to displacement of cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Ultrasound findings: These cysts appear as echo-free single structures connected in places to the meninges and causing damage due to compression of brain tissue or cerebrospinal fluid circulation. This may cause obstructive hydrocephalus. Clinical management: Repeated observations at short intervals. In cases of severe hydrocephalus and fetal maturity, premature delivery should be considered. Bleeding within the cysts may occur during labor. Procedure after birth: Small cysts can be monitored at regular intervals. Surgical intervention such as placement of a shunt or fenestration of the cyst may be necessary for large cysts causing symptoms (seizures, hydrocephalus). Prognosis: Generally good, depending on the location of the cyst and possible complications of surgical treatment. Recommendation for the mother: The prognosis is very good, as this is one of the few cases in which the cause of hydrocephalus can be treated successfully. References Bannister CM, Russell SA, Rimmer S, Mowle DH. Fetal arachnoid cysts: their site, progress, prognosis and differential diagnosis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1999; 9 (Suppl 1): 27–8. Blaicher W, Prayer D, Kuhle S, Deutinger J, Bernaschek G. Combined prenatal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in two fetuses with suspected arachnoid cysts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001; 18: 166–8. Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C. Surgical options in the treatment of interhemispheric arachnoid cysts. Surg Neurol 1996; 46: 212–21. D’Addario V, Pinto V, Meo F, Resta M. The specificity of ultrasound in the detection of fetal intracranialtumors. J Perinat Med 1998; 26: 480–5. Diakoumakis EE, Weinberg B, Mollin J. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of a suprasellar arachnoid cyst. J Ultrasound Med 1986; 5: 529–30. Elbers SE, Furness ME. Resolution of presumed arachnoid cyst in utero [review]. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 14: 353–5. Limacher F, Kaiser G, Da Silva V. Fetal intracranial invasive cysts: diagnosis, procedure and therapy using the example of a case report (arachnoid cyst). Ge-burtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1984; 44: 444–50. Meizner I, Barki Y, Tadmor R, Katz M. In utero ultrasonic detection of fetal arachnoid cyst. JCU J Clin Ultrasound 1988; 16: 506–9. Pilu G, Falco P, Perolo A et al. Differential diagnosis and outcome of fetal intracranial hypoechoic lesions: report of 21 cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 9: 229–36. Rafferty PG, Britton J, Penna L, Ville Y. Prenatal diagnosis of a large fetal arachnoid cyst. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998; 12: 358–61. Revel MP, Pons JC, Lelaidier C et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the fetus: a study of 20 cases performed without curarization. Prenat Diagn 1993; 13: 775–99. Sandler MA, Madrazo BL, Riga PM et al. Ultrasound case of the day: bilateral arachnoid cysts, diagnosed in utero. RadioGraphics 1988; 8: 358–61. Definition: Complete or partial absence of the corpus callosum, a bundle of white matter connecting the cerebral hemispheres. Incidence: One in 300–1500 births; however, when other anomalies of the central nervous system are present, it is detected in 50%. Mostly asymptomatic. Clinical history/genetics: Mostly sporadic; inherited cases with autosomal-dominant, autosomal-recessive, and X-linked transmission have been reported. Teratogens: Alcohol, rubella infection. Embryology: The corpus callosum develops between 11 and 16 gestational weeks. Failure of development may be partial or complete. Associated malformations: Hydrocephalus, microcephalus, pachygyria, lissencephaly. Dandy Walker syndrome is the most frequently associated anomaly. Anomalies of the kidneys, heart, lungs, and diaphragm are frequently seen. Ultrasound findings: In the absence of the corpus callosum, the third ventricle lies between the lateral ventricles. The posterior horns of the lateral ventricles are widened and are stretched ventrally (teardrop sign), and the medial borders run more parallel to the central echo than usual. The third ventricle may be connected to the lateral ventricles by a cystic communication. The septum pellucidum does not appear normal. The gyri of the hemispheres, which normally lie horizontally, tend to lie more ventrally in the absence of the corpus callosum. N.b.: a sagittal view through the midline is the best plane for diagnosing this condition. The diagnosis can be difficult and is often missed. Absence of the corpus callosum is rarely diagnosed before 16 weeks of gestation. Clinical management: Karyotyping. Detailed sonographic screening of the fetus and vaginal sonography may help further in cephalic presentation. Sonographic exclusion of other anomalies and fetal echocardiography. Magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated in uncertain cases. Fig. 2.9 Corpus callosum. Midline sagittal section at 22 + 0 weeks, showing the septum pellucidum (x) and the corpus callosum (arrows). Fig. 2.10 Corpus callosum. Frontal view through the forebrain. The anterior horns of both lateral ventricles (LV), septum pellucidum (x), and the cross-section of the corpus callosum (arrow) are well recognized. Fig. 2.12 Agenesis of the corpus callosum. Frontal view of the anterior part of the brain in agenesis of corpus callosum: “three lines sign.” The longitudinal fissure separating the cerebral hemispheres is widened. Fig. 2.13 Agenesis of the corpus callosum. Transverse section of the fetal head in agenesis of corpus callosum. The septum pellucidum cannot be demonstrated at 30 weeks of gestation. The lateral ventricles are enlarged. Fig. 2.15 Pericallosal artery. Midline sagittal section at 13 + 4 weeks. The pericallosal artery is depicted using the color Doppler mode. Fig. 2.16 Pericallosal artery. Midline sagittal section at 22 + 2 weeks. The normal course of the artery is seen. Achieving a reliable prognosis and definitely excluding other central nervous system anomalies are difficult tasks. In counseling the parents, expert advice from neuropediatrician and a neuropathologist should be taken. Diseases with autosomal-dominant inheritance in the parents, such as tuberous sclerosis and basal-cell nevus syndrome, should be excluded. It is important to search for fetal infection (TORCH). Regular sonographic checks do not per se show any changes in the findings, but the associated ventriculomegaly may develop later in pregnancy. Procedure after birth: There are no neurological deficits when agenesis of the corpus callosum is an isolated finding. Magnetic resonance imaging is considered the best method of confirming the diagnosis and excluding other central nervous system anomalies. Prognosis: The isolated condition remains mainly asymptomatic, but seizures may occur. The prognosis in some syndromes—for example, Dandy–Walker syndrome—is poor when associated with absence of the corpus callosum; otherwise a good prognosis is expected. Information for the patient: Up to 1% of adults have congenital agenesis of the corpus callosum, without their knowledge and without symptoms. In the absence of associated anomalies, mental development is normal. Self-Help Organization Title: The ACC Network Description: Helps individuals with agenesis, or other anomaly, of the corpus callosum, their families, and professionals. Helps identify others who are experiencing similar issues to share information and support. Phone support, information, newsletter and referrals. Coordinates an electronic discussion group on the internet. Scope: International network Founded: 1990 Address: University of Maine; 5749 Merrill Hall, Room 118, Orono, Maine 04469–5749, United States Telephone: 207–581–3119 Fax: 207–581–3120 E-mail: UM-ACC@maine.maine.edu References Achiron R, Achiron A. Development of the human fetal corpus callosum: a high-resolution, cross-sectional sonographic study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001; 18: 343–7. Comstock CH, Culp D, Gonzalez J, Boal DB. Agenesis of the corpus callosum in the fetus: its evolution and significance. J Ultrasound Med 1985; 4: 613–6. D’Ercole C, Girard N, Cravello L et al. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal corpus callosum agenesis by ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Prenat Diagn 1998; 18: 247–53. Greco P, Vimercati A, De Cosmo L, Laforgia N, Mautone A, Selvaggi L. Mild ventriculomegaly as a counselling challenge. Fetal Diagn Ther 2001; 16: 398–401. Maheut Le, Paillet C. Prenatal diagnosis of anomalies of the corpus callosum with ultrasound: the echographist’s point of view. Neurochirurgie 1998; 44: 85–92. Rapp B, Perrotin F, Marret H, Sembely-Taveau C, Lansac J, Body G. [Value of fetal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging for the prenatal diagnosis and prognosis of corpus callosum agenesis; in French.] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2002; 31: 173–82. Sandri F, Pilu G, Cerisoli M, Bovicelli L, Alvisi C, Salvioli GP. Sonographic diagnosis of agenesis of the corpus callosum in the fetus and newborn infant. Am J Perinatol 1988; 5: 226–31. Timor-Tritsch TI, Monteagudo A, Haratz-Rubinstein RN, Levine RU. Transvaginal sonographic detection of adducted thumbs, hydrocephalus, and agenesis of the corpus callosum at 22 postmenstrual weeks: the masa spectrum or L1 spectrum: a case report and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn 1996; 16: 543–8. Valat AS, Dehouck MB, Dufour P et al. Fetal cerebral ventriculomegaly: etiology and outcome—report of 141 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1998; 27: 782–9. Vergani P, Ghidini A, Mariam S, Greppi P, Negri R. Antenatal sonographic findings of agenesis of corpus callosum. Am J Perinatol 1988; 5:105–8. Definition: The Dandy–Walker syndrome is characterized by a cyst in the posterior fossa that communicates with the fourth ventricle, a defect in the cerebellar vermis, and varying degrees of hydrocephalus. Incidence: One in 25 000–1 : 30000 births, representing about 4% of hydrocephalic cases. Clinical history/genetics: May appear sporadically, or may show autosomal-recessive or X-linked inheritance. Teratogens: Congenital infections. Embryology: The Dandy–Walker syndrome develops in the 5th to 6th week after conception. Associated malformations: In 50% of the cases, other intracranial malformations are detected, especially agenesis of the corpus callosum. In 35 %, other extracranial anomalies are evident such as those affecting the face (cleft lip and palate) or the heart (ventricular septal defects). Chromosomal aberrations are found in 15–30%. Dandy–Walker cysts are found often in the presence of encephalocele and neural tube defects. Associated syndromes: These include Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, Jubert syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome, triploidy, trisomy 18, arthrogryposis, CHARGE association, Fryns syndrome, MURCS association. Fig. 2.18 Dandy–Walker syndrome. Demonstration of the posterior cranial fossa in a case of Dandy–Walker syndrome. Cystic widening of the region below the cerebellar hemispheres is seen. Ultrasound findings: Dandy–Walker cyst, seen as an echo-free structure, separates the cerebellar hemispheres. The cyst communicates with the fourth ventricle. The cerebellar vermis may be partially or totally absent. Hypoplasia of the cerebellum may also be present. The third ventricle and the lateral ventricles are widened in the presence of larger cysts. Caution: The frequent finding of small cysts under the cerebellum may not be pathologic. A connection between the fourth ventricle and the cisterna magna is evident until 15–17 weeks. Clinical management: Further sonographic screening, including fetal echocardiography. Karyotyping and search for infections (TORCH). Counseling with a neurosurgeon, neuropediatrician, or neuropathologist. If the mother decides to continue with the pregnancy, regular sonographic monitoring. Premature delivery should be considered if the hydrocephalus enlarges rapidly. This option is disputed because of bad prognosis. Prognosis is worsened if agenesis of the corpus callosum is also detected. If the diagnosis is uncertain, magnetic resonance imaging during the pregnancy can be useful in deciding the clinical management. Bleeding within the cysts may occur, and this should be borne in mind when choosing the mode of delivery. Procedure after birth: Normal postnatal care for the newborn. In most infants with absence of intrauterine hydrocephalus, development of hydrocephalus occurs within 2 months after birth. Treatment for the Dandy–Walker cyst is only then indicated if the child develops symptoms (difficulty in swallowing, aspiration, a weak cry, underdeveloped sucking reflex). The usual management is placement of a cystoperitoneal shunt. Prognosis: The overall postnatal mortality is about 35 % and depends on the accompanying malformations. A third of the survivors have an IQ of over 80. Placement of a shunt is often necessary due to the presence of hydrocephalus. Recommendation for the mother: The child should be investigated thoroughly, including genetic counseling. The parents should be advised regarding the risk for the next pregnancy. Self-Help Organization Title: Dandy–Walker Syndrome Network Description: Provides mutual support, information and networking for families affected by Dandy–Walker syndrome. Phone support. Scope: International network Founded: 1993 Telephone: 612–423–4008 References Achiron R, Achiron A, Yagel S. First trimester transvaginal sonographic diagnosis of Dandy–Walker malformation. J Clin Ultrasound 1993; 21: 62–4. Bernard JP, Moscoso G, Renier D, Ville Y. Cystic malformations of the posterior fossa [review]. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21: 1064-9. Dempsey PJ, Koch HJ. In utero diagnosis of the Dandy–Walker syndrome: differentiation from extra-axial posterior fossa cyst. JCU J Clin Ultrasound 1981; 9: 403–5. Nyberg DA, Cyr DR, Mack LA, Fitzsimmons J, Hickok D, Mahony BS. The Dandy–Walker malformation: prenatal sonographic diagnosis and its clinical significance. J Ultrasound Med 1988; 7: 65–71. Pilu G, Romero R, De Palma L et al. Antenatal diagnosis and obstetric management of Dandy–Walker syndrome. J Reprod Med 1986; 31: 1017–22. Serlo W, Kirkinen P, Heikkinen E, Jouppila P. Ante- and postnatal evaluation of the Dandy–Walker syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst 1985; 1: 148–51. Ulm B, Ulm MR, Deutinger J, Bernaschek G. Dandy–Walker malformation diagnosed before 21 weeks of gestation: associated malformations and chromosomal abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 10: 167–70. Yuh WT, Nguyen HD, Fisher DJ et al. MR of fetal central nervous system abnormalities. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 459–64. Zimmermann R, Biedermann K, Wildhaber J, Huch A. Early recognition of fetal abnormalities by transvagi-nal ultrasonography. Ultraschall Med 1993; 14: 35–9. Definition:

2 The Central Nervous System and the Eye

Anencephaly

Aqueduct Stenosis

Arachnoid Cysts

Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum

Dandy–Walker Syndrome

Encephalocele

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree