Chapter 4 The ligaments of the lumbar spine

Topographically, the ligaments of the lumbar spine may be classified into four groups:

1 Those ligaments that interconnect the vertebral bodies.

2 Those ligaments that interconnect the posterior elements.

Ligaments of the vertebral bodies

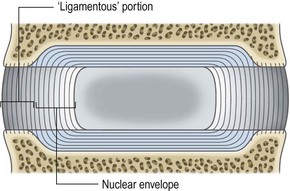

Anuli fibrosi

As described in Chapter 2, each anulus fibrosus consists of collagen fibres running from one vertebral body to the next and arranged in concentric lamellae. Furthermore, the deeper lamellae of collagen are continuous with the collagen fibres in the fibrocartilaginous vertebral endplates (see Ch. 2). By surrounding the nucleus pulposus, these inner layers of the anulus fibrosus constitute a capsule or envelope around the nucleus, whereupon it could be inferred that their principal function is to retain the nucleus pulposus (Fig. 4.1).

In contrast, the outer fibres of the anulus fibrosus are attached to the ring apophysis (see Ch. 2). For various reasons it is these fibres that could be inferred to be the principal ‘ligamentous’ portion of the anulus fibrosus. Foremost, like other ligaments they are attached to separate bones, and like other ligaments they consist largely of type I collagen, which is designed to resist tension (see Ch. 2). Such tension arises during rocking or twisting movements of the vertebral bodies. During these movements the peripheral edges of the vertebral bodies undergo more separation than their more central parts, and the tensile stresses applied to the peripheral anulus are greater than those applied to the inner anulus. In resisting these movements the peripheral fibres of the anulus fibrosus are subject to the same demands as conventional ligaments, and function accordingly.

As outlined in Chapter 2 and considered further in Chapter 8, the anulus fibrosus functions as a ligament in resisting distraction, bending, sliding and twisting movements of the intervertebral joint. Thus, the anulus fibrosus is called upon to function as a ligament whenever the lumbar spine moves. It is only during weight-bearing that it functions in concert with the nucleus pulposus.

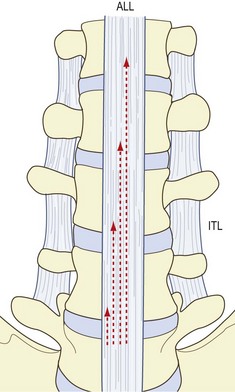

Anterior longitudinal ligament

Conventional descriptions maintain that the anterior longitudinal ligament is a long band which covers the anterior aspects of the lumbar vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs (Fig. 4.2).1 Although well developed in the lumbar region, this ligament is not restricted to that region. Inferiorly it extends into the sacrum, and superiorly it continues into the thoracic and cervical regions to cover the anterior surface of the entire vertebral column.

Structurally, the anterior longitudinal ligament is said to consist of several sets of collagen fibres.1 There are short fibres that span each interbody joint, covering the intervertebral disc and attaching to the margins of the vertebral bodies (Figs. 4.2, 4.3). These fibres are inserted into the bone of the anterior surface of the vertebral bodies or into the overlying periosteum.2,3 Some early authors interpreted these fibres as being part of the anulus fibrosus,4 and there is a tendency in some contemporary circles to interpret these fibres as constituting a ‘disc capsule’. However, embryologically, their attachments are always associated with cortical bone, as are ligaments in general, whereas the anulus fibrosus proper is attached to the vertebral endplate.2 Even those fibres of the adult anulus that attach to bone do so by being secondarily incorporated into the ring apophysis (Ch. 2), which is not cortical bone. Because of these developmental differences, the deep, short fibres of the anterior longitudinal ligament should not be considered to be part of the anulus fibrosus.

Because of its strictly longitudinal disposition, the anterior longitudinal ligament serves principally to resist vertical separation of the anterior ends of the vertebral bodies. In doing so, it functions during extension movements of the intervertebral joints and resists anterior bowing of the lumbar spine (see Ch. 5).

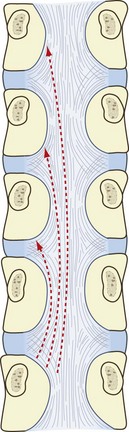

Posterior longitudinal ligament

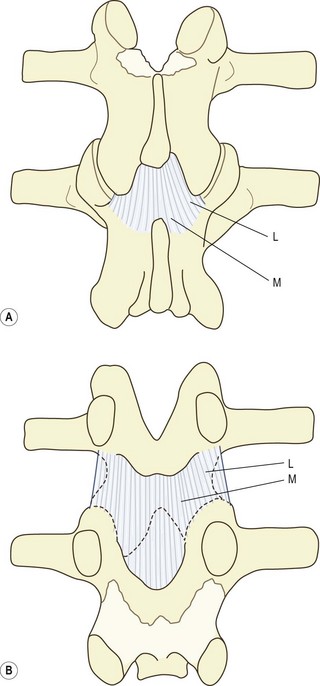

Like the anterior longitudinal ligament, the posterior longitudinal ligament is represented throughout the vertebral column. In the lumbar region, it forms a narrow band over the backs of the vertebral bodies but expands laterally over the backs of the intervertebral discs to give it a serrated, or saw-toothed, appearance (Fig. 4.4). Its fibres mesh with those of the anuli fibrosi but penetrate through the anuli to attach to the posterior margins of the vertebral bodies.3 The deepest and shortest fibres of the posterior longitudinal ligament span two intervertebral discs. Starting at the superior margin of one vertebra, they attach to the inferior margin of the vertebra two levels above, describing a curve concave laterally as they do so. Longer, more superficial fibres span three, four and even five vertebrae (see Figs 4.3 and 4.4).

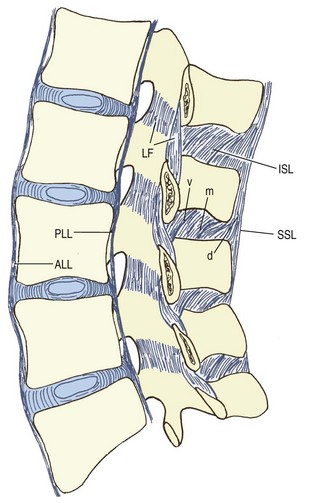

Ligaments of the posterior elements

The named ligaments of the posterior elements are the ligamentum flavum, the interspinous ligaments, and the supraspinous ligaments. In some respects, the capsules of the zygapophysial joints act like ligaments to prevent certain movements, and in a functional sense they can be considered to be one of the ligaments of the posterior elements. Indeed, their biomechanical role in this regard is quite substantial (see Ch. 8). However, their identity as capsules of the zygapophysial joints is so clear that they have been described formally in that context.

Ligamentum flavum

The ligamentum flavum is a short but thick ligament that joins the laminae of consecutive vertebrae. At each intersegmental level, the ligamentum flavum is a paired structure, being represented symmetrically on both left and right sides. On each side, the upper attachment of the ligament is to the lower half of the anterior surface of the lamina and the inferior aspect of the pedicle (Figs. 4.3, 4.5). Its smooth surface blends perfectly with the smooth surface of the upper half of the lamina. Traced inferiorly, on each side the ligament divides into a medial and lateral portion.5–7 The medial portion passes to the back of the next lower lamina and attaches to the rough area located on the upper quarter or so of the dorsal surface of that lamina (see Fig. 4.5). The lateral portion passes in front of the zygapophysial joint formed by the two vertebrae that the ligament connects. It attaches to the anterior aspects of the inferior and superior articular processes of that joint, and forms its anterior capsule. The most lateral fibres extend along the root of the superior articular process as far as the next lower pedicle to which they are attached.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree