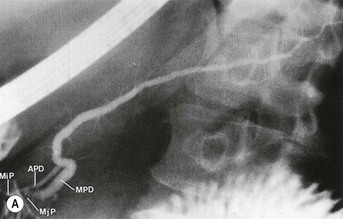

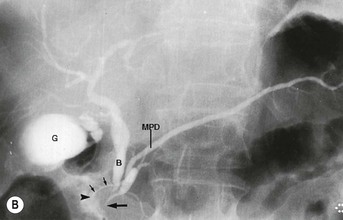

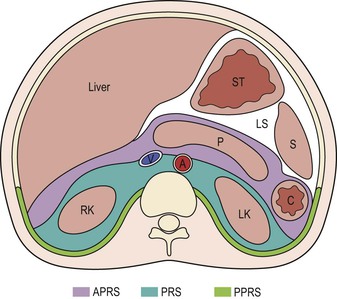

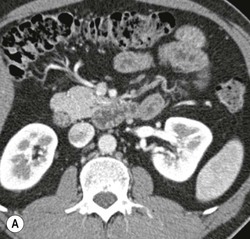

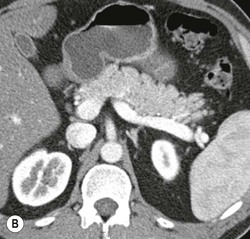

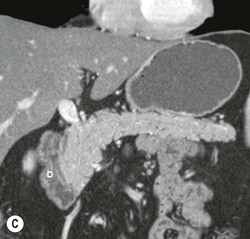

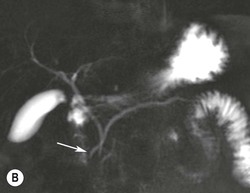

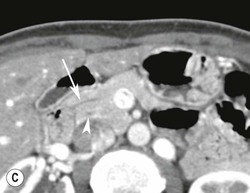

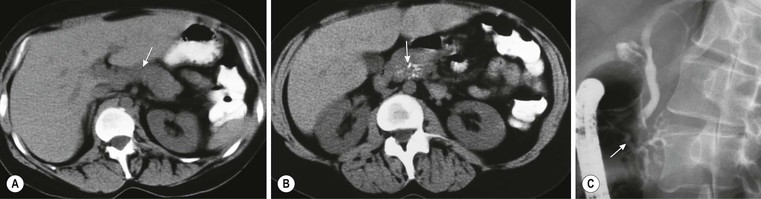

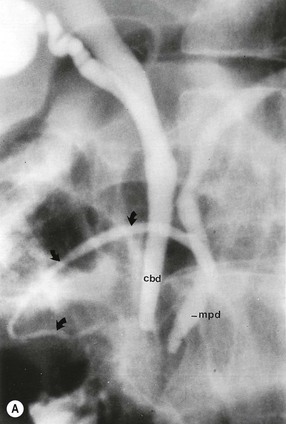

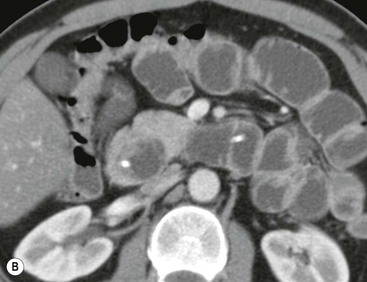

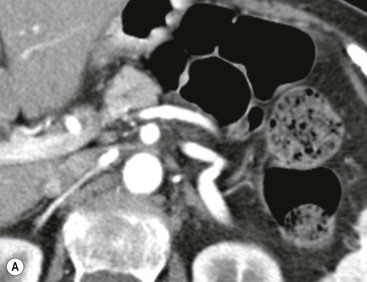

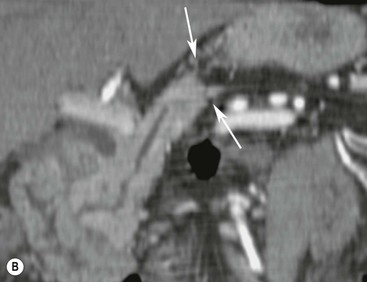

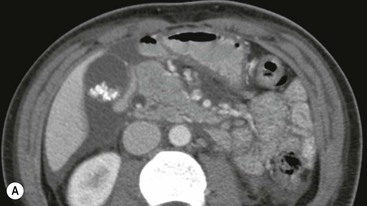

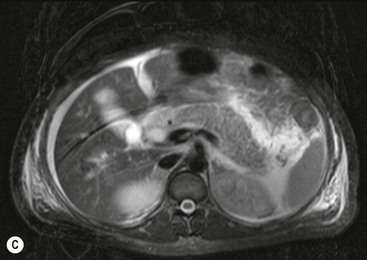

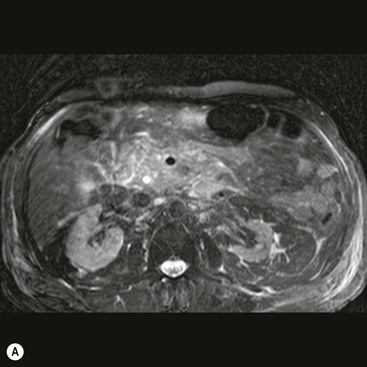

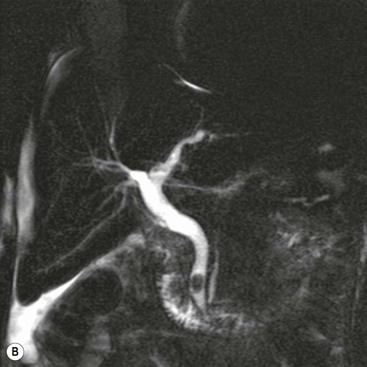

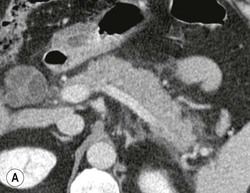

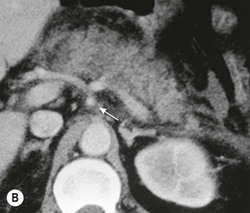

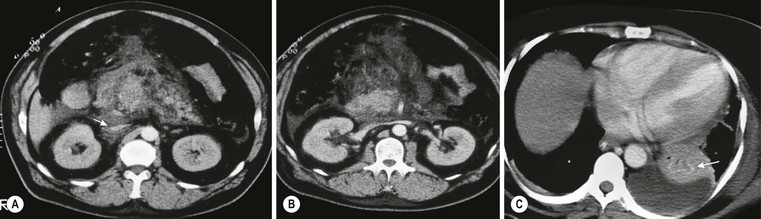

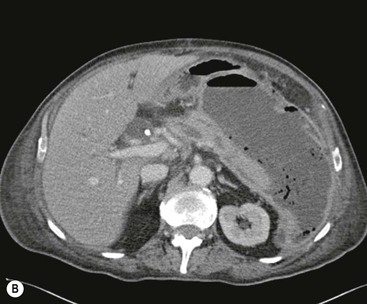

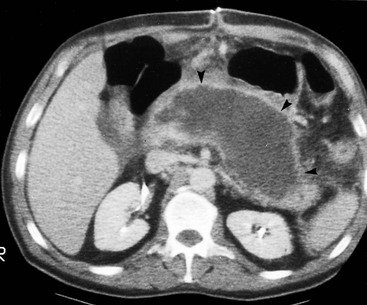

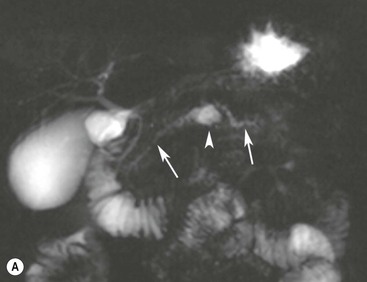

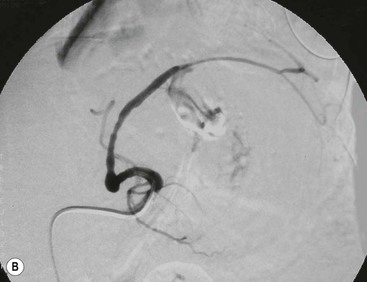

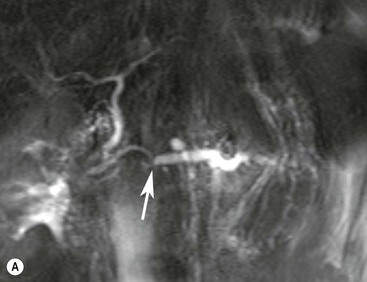

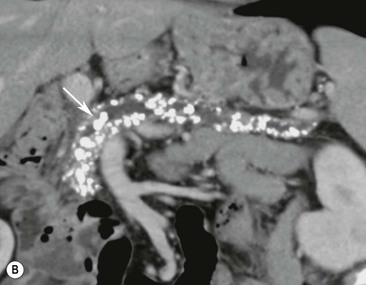

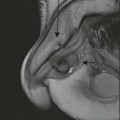

Wolfgang Schima, E. Jane Adam, Robert A. Morgan The pancreas develops in two parts, both of which arise from the endoderm of the primitive duodenum. The dorsal part or anlage is the first to appear, as a diverticulum from the dorsal wall of the duodenum. This eventually forms the whole of the neck, body and tail of the gland, together with part of the head. The ventral anlage develops more caudally as a diverticulum from the developing bile duct at the point where the latter opens into the duodenum. Soon after the appearance of the two parts, the duodenum undergoes partial rotation and they approximate each other and fuse. Until this stage the dorsal duct, the duct of Santorini, opens into the duodenum proximal to the major papilla (ampulla of Vater) at the minor papilla, whereas the ventral duct, the duct of Wirsung, which is joined with the lower common bile duct, opens into the major papilla. In the majority of cases, fusion of the two ducts occurs at the junction of the head and body of the gland (Fig. 33-1). Thus the main pancreatic duct opens into the major papilla. The pancreas lies in the most anterior of the three retroperitoneal compartments, the anterior pararenal space. Ventrally, this is bounded by the posterior parietal peritoneum. Dorsally, the space is bounded by the anterior renal or Gerota’s fascia and more laterally by the lateroconal fascia (Fig. 33-2). Other structures occupying the anterior pararenal space include the duodenal loop and ascending and descending colon. The pancreas is surrounded by retroperitoneal fat (Fig. 33-3). The position, size and configuration of the pancreas are very variable, depending on body habitus and the size and shape of adjacent organs and this inherent variation makes it difficult to define the normal size of the pancreas. The gland is relatively larger in adolescents than adults and becomes smaller with increasing age. Several congenital anomalies of the pancreas may occur secondary to failure of normal embryological development. Pancreas divisum is the commonest congenital pancreatic anomaly, characterised by the failure of normal fusion of the dorsal and ventral anlagen in the fetal period in approximately 5% of the population. The dorsal and ventral ducts fail to fuse (Fig. 33-4), with the duct of Wirsung (duct of the ventral anlage) draining only the head of the pancreas via the major papilla and the duct of Santorini (dorsal anlage) draining the body and tail via the more cranially and anteriorly positioned minor papilla. This anomaly may result in functional stenosis and pancreatitis (Fig. 33-5). In an ERCP-based study, of the 94 patients identified to have pancreas divisum, 57% had evidence of chronic pancreatitis.1 The prevalence of pancreas divisum was much higher in patients with chronic/recurrent ‘idiopathic’ pancreatitis (43%/33%) than in the general population (2.6%).2 An increased incidence of pancreatic malignancy has been described,3 possibly based on the increased prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in this group. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) reliably enables visualisation of panceas divisum. Stimulation of pancreatic secretions with secretin-enhanced MRCP allows visualisation of functional stenoses at the minor papilla. Annular pancreas is the second most common congenital anomaly and is the result of failure of normal rotation during development. This results in pancreatic tissue partially or completely encircling the duodenum. The anomaly may cause proximal duodenal dilatation and symptomatic duodenal narrowing. The diagnosis may be suspected if barium studies show narrowing of the duodenum at the level of the major papilla or pancreatic tissue is seen surrounding the second part of the duodenum on CT. ERCP or MRCP can confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating a segment of pancreatic duct encircling the duodenum (Fig. 33-6A). With contrast-enhanced CT a circumferential rim of pancreatic tissue is demonstrated (Fig. 33-6B). Agenesis of the whole pancreas is exceptionally rare, but agenesis or hypoplasia of the dorsal anlage may occur.4 In these cases CT may show absence of the body and tail of the gland, with a corresponding short duct in the dorsal anlage (Fig. 33-7). Ectopic islands of pancreatic tissue may be found remote from the gland, most commonly in the gastric or duodenal wall. The diagnosis is usually made incidentally during barium examination or upper gastrointestinal endoscopy when the ectopic pancreatic tissue is seen as a polypoid nodule, often with central umbilication representing a rudimentary pancreatic duct. There are many causes of acute pancreatitis, including alcohol, cholelithiasis (Fig. 33-8), trauma, iatrogenic (e.g. post-ERCP) as well as metabolic disorders such as hyperlipidaemia and hypercalcaemia. Pancreatitis may also be associated with viral infections, examples being mumps and cytomegalovirus. Numerous drugs are known to cause acute pancreatitis. In 10–30% of cases there is no apparent cause, in which case it is classified as idiopathic pancreatitis, although there is evidence that some of these cases are associated with congenital duct anomalies.3 In many cases the diagnosis is a straightforward clinical one, for example in a patient with a history of heavy alcohol intake, upper abdominal pain and hyperamylasaemia or a raised plasma lipase. In 2008, an international group of experts in the field of pancreatitis, led by the Acute Pancreatitis Classification Group, gathered input using an iterative, web-based consultation process led by a working group, and revised the Atlanta classification system in an effort to improve clinical assessment and management of acute pancreatitis and to standardise terms for peripancreatic fluid collections, pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis and how these entities evolve over the time, as well as any complications that may arise.5–7 The revised Atlanta classification (2012) of acute pancreatitis divides the condition into interstitial oedematous pancreatitis and necrotising pancreatitis, (formerly termed mild and severe acute pancreatitis).5–7 This morphological classification system is based on findings on contrast-enhanced CT. Briefly, the imaging findings in interstitial oedematous pancreatitis include focal or diffuse enlargement of the gland, with normal homogeneous enhancement or slightly heterogeneous enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma, which is attributable to oedema.5 Necrotising pancreatitis is seen in fewer than 5% of patients and appears on contrast-enhanced CT images as lack of parenchymal enhancement.5 In the 2012 classification, necrotising pancreatitis is further subdivided into parenchymal necrosis alone, peripancreatic necrosis alone and a combined type (areas of pancreatic parenchymal and peripancreatic necrosis) with and without infection.5 Peripancreatic necrosis is seen as heterogeneous areas of non-enhancement that contain non-liquefied components.5 Pancreatic parenchymal necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis is characterised on imaging by a combination of imaging features observed with pancreatic parenchymal necrosis alone and peripancreatic necrosis.5 In (mild) interstitial oedematous pancreatitis, proteolytic enzymes injure the acinar cell, causing oedema and swelling of the gland, but the inflammatory response is not strong enough to cause necrosis. In interstitial oedematous pancreatitis, which constitutes 70–80% of cases, the ultrasound (US) appearances may be entirely normal but common findings may include generalised (or less commonly, focal) enlargement of the gland with reduced reflectivity. The pancreatic margins may be difficult to define and peripancreatic fluid may be visualised. The presence of necrosis (necrotising pancreatitis) indicates that the inflammatory response has triggered cellular apoptosis.7 The major determinant of morbidity and mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis is the development of pancreatic necrosis.8 Conventional US cannot reliably detect this complication. Serum markers, such as C-reactive protein, have been identified for the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis but their usefulness is limited by their specificity and/or availability. The clinical grading of severity has utilised a number of scoring systems such as Ranson’s, APACHE-II, Marshall scoring system or BISAP score. There is an ongoing discussion about the use of imaging in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Although in mild acute pancreatitis US may suffice to rule out complications and to assess for aetiologies such as gallstones, contrast-enhanced CT has emerged as the main diagnostic pillar in suspected or confirmed acute pancreatitis. Contrast-enhanced CT is the investigation of choice to assess the presence and extent of pancreatic necrosis, the extent of peripancreatic inflammation and necrosis and the presence of fluid collections.9 The CT severity index (CTSI) for staging of acute pancreatitis has been developed,10 considering the amount of fluid collections and the presence or absence of pancreatic necrosis (Table 33-1). The CTSI correlates with morbidity and mortality (Table 33-2). However, it has recently been shown that CT scoring does not supersede clinical scoring systems (BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II) for identification of patients with severe pancreatitis.11,12 TABLE 33-1 Scoring System for Severity of Acute Pancreatitis: CT Severity Index (CTSI) TABLE 33-2 CT Severity Index (CTSI) vs Morbidity and Mortality According to the revised Atlanta classification, contrast-enhanced CT is the primary tool for assessing and staging patients with acute pancreatitis, helping to assess for complications and assessing response to treatment.5 Not all patients with acute pancreatitis require contrast-enhanced CT imaging. Recent UK guidelines suggest that immediate CT is indicated if the clinical and biochemical findings are inconclusive, especially if signs raise the possibility of an alternative abdominal emergency.13 If carried out very early (in the first 24 h after clinical onset), it is also possible that CT may underestimate the degree of necrosis and in most patients it will not influence management in the first few days. The optimal time for performance of contrast-enhanced CT imaging is greater than 72 h after the onset of symptoms.5 CT imaging should be repeated if clinical picture changes, such as development of fever or drop in haematocrit.5 Also, patients with persisting or new organ failure and those with continuing pain or signs of sepsis will require a contrast-enhanced study as the presence of necrosis as detected on CT has a high correlation with the risk of local and systemic complications.12 CT is the most reliable imaging technique for the staging of acute pancreatitis, if performed with IV contrast medium. Other than how CT is performed for pancreatic cancer detection and staging, a single venous phase CT image (100–150 mL at 4 mL/s with a fixed delay of 70 s) will be sufficient to stage acute pancreatitis, and unenhanced or arterial-phase imaging is not routinely necessary.14 In the clinical context of acute pancreatitis, CT protocol design should consider radiation exposure, as many patients with severe acute pancreatitis are young and will require several sessions of CT imaging during the course of their disease.14 It has been shown that early removal of bile duct stones (by ERCP) may influence the prognosis in patients with biliary pancreatitis and obstructive jaundice.15–17 Thus MRCP (or if available endosonography) should be used to detect choledocholithiasis and to aid in selection of candidates for ERCP, if performed without delay (Fig. 33-9).18 MR imaging may also have a role in detecting non-liquefied material within a pancreatic or peripancreatic collection.5 As already discussed, the imaging findings in interstitial oedematous pancreatitis include focal or diffuse enlargement of the gland, with normal homogeneous enhancement (Figs. 33-10 and 33-11) or slightly heterogeneous enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma, which is attributable to oedema.5 It is important to highlight, however, that on a contrast-enhanced CT image obtained in the first few days after presentation with acute pancreatitis, the pancreas may demonstrate increased enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma, which cannot be definitively characterised as either acute oedematous pancreatitis or necrotising pancreatitis.5,6 In this situation, it is important for the radiologist to conclude that the CT is indeterminate and that contrast-enhanced CT imaging should be repeated 5–7 days later, if the patient’s clinical status is not improving.5 Fluid collections may be seen around the pancreas, in the pararenal space along fascial planes, at the mesenteric root or in the bursa omentalis. For grading of acute pancreatitis, the CT severity index has been proposed, which takes into account the presence of gland swelling, peripancreatic fluid collections and the presence of necrosis as an indicator for the prognosis.10 This is the hallmark of severe acute pancreatitis. The revised Atlanta classification distinguishes three forms of acute necrotising pancreatitis: pancreatic parenchymal necrosis alone, peripancreatic necrosis alone, and pancreatic necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis.5,6 All three types can be sterile or infected. Necrotic glandular tissue is seen as an area of non-enhancement within the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 33-12). With time, non-viable or necrotic tissue pancreatic parenchyma or peripancreatic fat liquefies.5 The presence of peripancreatic necrosis alone carries a much better prognosis than parenchymal necrosis.5 The extent of necrosis may be categorised into less than 30%, 30–50% or more than 50% of the gland. Patients with CT evidence of more than 30% necrosis have an overall reported mortality rate of 29%.19 In the study of Heiss et al.20 two CT features correlated with mortality: first, the presence of necrosis of more than one part (i.e. head, body or tail) of the pancreas and, secondly, the presence of distant fluid collections (in the posterior pararenal space and/or paracolic gutter). Infected necrosis occurs in 20–70% of patients with necrotic pancreatic tissue21 and is responsible for an estimated 80% of deaths from acute pancreatitis. The presence of gas bubbles within an area of necrotic tissue (in the absence of recent intervention in the region or existence of a communication between gastrointestinal tract and the pancreatic collection/area of necrosis) is highly suggestive of infection (Fig. 33-13). Confirmation of infection requires fine-needle aspiration. If infection is shown to be present within necrotic tissue, percutaneous drainage may not evacuate thick debris. Surgical intervention is the method of choice, although recent studies have shown that a conservative approach avoiding open necrosectomy lowers the mortality considerably (8.3 vs 45%).22 Thus necrosectomy is nowadays reserved for patients with concomitant intra-abdominal complications not amenable to conservative therapy.22 Acute pancreatitis can be accompanied by pancreatic parenchymal or peripancreatic collections.5,6 The acute collections are referred to as either acute peripancreatic fluid collections (APFCs) or as acute necrotic collections (ANCs), depending on the presence or absence of pancreatic necrosis.5,6 Thus, in the acute period interstitial oedematous pancreatitis will be associated with APFCs and after a period of 4 weeks by a pseudocyst. Necrotising pancreatitis in its three forms is potentially associated with ANCs and after a period of 4 weeks by walled-off necrosis (WON). All of these collections can be sterile or infected.5,6 APFCs in general are self-limiting and are reabsorbed within the first few weeks, and usually do not become infected. These collections therefore rarely require any intervention unless they become infected.5,6 If an APFC is not resolved within 4 weeks after onset of acute pancreatitis, it transitions into a pancreatic pseudocyst. Pseudocysts develop as a complication of acute pancreatitis in 10–20% of cases.5,6 The imaging characteristics of a pseudocyst, according to the 2012 classification, include a round or oval fluid collection surrounded by a well-defined enhancing wall or capsule. Pseudocysts should not contain any non-liquefied components within the fluid collection.5,6 In some cases, pseudocysts may communicate with the pancreatic duct, a feature which can have a bearing on management of these fluid collections. Pseudocysts can become infected and superinfection can be manifest as air within the collection on contrast-enhanced CT imaging. In the first 4 weeks after development of necrotising pancreatitis, a persistent collection is called an ANC.5,6 This collection may contain variable amounts of debris and necrotic material. The natural history of ANC is progressive liquefaction over a 3- to 6-week period.5,6 An important change with the new classification is that any collection in the pancreatic parenchyma should be called an ANC and not a pseudocyst. An ANC may have a communication to the pancreatic duct.5,6 Acute necrotic collection associated with NP, usually 4 weeks or later following first development of symptoms, develops a thickened non-epithelialised wall and is called a WON. Like ANC, WON can involve the pancreas, and/or the peripancreatic area.5,6 Any fluid collection that occupies or replaces the pancreas should be called a WON after 4 weeks. Like APFC, ANC and pseudocyts, WON can be sterile or infected. Unlike pseudocyst, WON may contain varying amounts of non-liquefied material and therefore, if infected, is less easily treated by percutaneous catheter drainage when compared to a pseudocyst.5,6 Infected WON has replaced the term ‘pancreatic abscess’, which was previously reported to occur in 3% of patients with severe pancreatitis22 (Fig. 33-14). Gas bubbles are a helpful pointer to the presence of infection, but most infected WONs appear as thick-walled fluid collections. It is also important to remember, that the presence of air bubbles within a WON is not always indicative of infection, as air bubbles can also be encountered when communication between WON and gastrointestinal tract exists. Imaging-based differentiation of sterile and infected fluid collections can be challenging. Thus, clinical signs and symptoms of infection should be correlated with laboratory indices of infection such as white cell count and C-reactive protein. If infection is confirmed by fine-needle aspiration and the collection is at least partially liquefied, percutaneous catheter drainage may be attempted but large catheters (up to 30Fr) may be required (Fig. 33-15). As discussed previously, most APFCs resolve spontaneously without clinical sequelae.5,6,23 In some cases, they persist and over several weeks develop into pseudocysts, which classically have a fibrous capsule (Figs. 33-16–33-18). Pseudocysts may rarely even extend into the mediastinum. More than 70% of pseudocysts resolve spontaneously or decrease in size. Thus a wait-and-see policy for more than 6 weeks is suggested for asymptomatic pseudocysts.24 However, they may be associated with complications, including rupture, infection (Fig. 33-19), haemorrhage (Fig. 33-20), pain, biliary or pancreatic duct obstruction (Fig. 33-18), or gastrointestinal tract involvement. Effective treatment may be provided by percutaneous catheter drainage. This is a not uncommon complication of pancreatitis. Intrapancreatic and peripancreatic arteries and veins may be eroded or thrombosed by the digestive effect of pancreatic enzymes or as a result of compression by a pseudocyst. Vascular involvement may be manifested by thombosis of an artery or vein. The splenic artery and vein are especially at risk of being involved in acute pancreatitis, leading to splenic vein thrombosis with infarction or splenic haemorrhage.25 Enzymatic damage to the splenic or gastroduodenal artery can cause development of a pseudoaneurysm, rupture of which may lead to life-threatening bleeding. Contrast-enhanced CT images reliably identify the site of vascular involvement. In cases of severe acute haemorrhage or pseudoaneurysm formation, angiography and vascular embolisation may be an alternative to surgery (Fig. 33-20). The gastrointestinal tract is frequently involved by direct extension of the inflammatory process from the inflamed pancreas and this can result in oedema, necrosis, or perforation of the wall of the stomach or duodenum. Patients are at higher risk if there is close contact between bowel loops and the inflammatory process. Secondary involvement of bowel may occur when pancreatic enzymes permeate through mesenteric attachments, or secondary to vascular complications resulting in bowel ischaemia. Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is an irreversible inflammatory disease of the pancreas, resulting in fibrosis. Patients often give a history of multiple prior attacks of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 33-21). Chronic pancreatitis produces abdominal pain and loss of exocrine and endocrine function, resulting in weight loss, steatorrhoea and diabetes. A variety of classification systems have been proposed, including the Marseille, the Manchester, the Cambridge and the Zurich classifications.26 These classification systems are either based on histology or ductal morphology at ERCP, or a combination of ERCP morphology and clinical symptoms. For cross-sectional imaging, the diagnosis is based on ductal morphology and other findings. Plain abdominal radiographs may reveal pancreatic calcification with or without evidence of a mass. The presence of calcification is highly suggestive of a diagnosis of chronic alcohol-related pancreatitis. The size of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis is very variable. Atrophy of the whole gland is a common consequence of chronic inflammation and fibrosis but enlargement of the gland may also be seen, either in a generalised or focal pattern. On US the internal echo texture may be heterogeneous. Dilatation of the side branches and of the main pancreatic duct (beyond its usual size of up to 2.5 mm) is, in the absence of an obstructing mass, a key feature of CP. Intraductal stones may seen with CT or MRCP (Fig. 33-22), with secondary dilatation of the common bile duct. Early CT diagnosis of CP is difficult, as no single imaging feature is pathognomonic for CP. When a combination of at least three out of the four imaging features, i.e. parenchymal calcifications, intraductal calcifications, parenchymal atrophy and cystic lesions, is present, diagnosis of CP can be made with high specificity.27

The Pancreas

Embryology

The Normal Pancreas

Congenital Anomalies

Pancreas Divisum

Annular Pancreas

Pancreatic Agenesis, Hypoplasia and Ectopic Pancreas

Acute Pancreatitis

CT Features

Score

Grade

Normal gland

0

Focal/diffuse enlargement

1

Peripancreatic inflammatory change

2

Single pancreatic fluid collection

3

Two or more fluid collections or abscess

4

Necrosis

None

0

<30%

2

30–50%

4

>50%

6

Score

Morbidity (%)

Mortality (%)

0–3

8

3

4–6

35

6

7–10

92

17

Imaging in Acute Pancreatitis

Interstitial Oedematous Pancreatitis

Necrotising Pancreatitis

Pancreatic and Peripancreatic Collections

Pseudocyst

Acute Necrotic Collection (ANC)

Walled-Off Necrosis (WON)

Pseudocysts

Vascular Complications

Gastrointestinal Involvement

Chronic Pancreatitis

The Pancreas

Chapter 33