Pelvis Checklists

1

1

Imaging assessment

Radiographic examination

AP

Oblique views

Internal oblique (obturator view)

External oblique (iliac view)

Inlet view

Outlet view

Computed tomography (CT)

Axial

Reformatted images

Coronal

Sagittal

3-D

Volume-rendered semitransparent three-dimensional images to simulate radiographic views

AP, inlet, outlet, iliac oblique, obturator oblique

Lateral view of high quality

Not possible to obtain radiographically

2

2

Anatomic features

Pelvic ring

Composed of two innominate bones and the sacrum

Joined posteriorly by the two sacroiliac joints

Joined anteriorly by the symphysis pubis

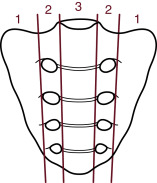

Ring consists of two arches

The posterior or femorosacral arch extends from one acetabulum to the other.

- (1)

The main weight-bearing component of the pelvis

- (2)

The stronger of the two arches

- (1)

The tie or anterior arch extends inferiorly and anteriorly from each acetabulum.

- (1)

The weaker arch

- (2)

Fractures more likely to occur in anterior arch

- (1)

Pelvic ligaments

Stability of pelvis is dependent on the integrity of strong ligaments.

Posterior and anterior sacroiliac ligaments

- (1)

Posterior sacroiliac ligaments are strongest ligaments in the body.

- (1)

Sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments

- (1.)

Extend from the sacrum to the ischial spine and tuberosity

- (1.)

Iliolumbar and iliosacral ligaments

- (1.)

Attach fifth lumbar transverse processes to ilium and sacrum

- (1.)

3

3

Stability of fractures variable

Stable fractures

In general

Single fracture limited to either anterior or posterior arch

- (1.)

Most common in anterior arch

- (2.)

Isolated fxs of posterior arch are rare.

- (1.)

Principal pelvic ligaments remain intact.

Common stable fractures

Pubic rami

Body of pubis

Iliac – periphery of iliac wing (Duverney fracture)

Sacrum – transverse fracture below sciatic notch

Coccyx

Unstable fractures

In general

Fractures involve both anterior and posterior arches.

One or more principal pelvic ligaments disrupted

Common types of unstable fractures

Ipsilateral displaced fractures of both anterior and posterior arches

Pelvic dislocation – disruption of pubic symphysis and SI joint or joints

Commonly referred to as an “open book” fracture

Unilateral fractures of pubic rami with sacral ala or iliac fracture opposite side of pelvis

Commonly referred to as a bucket handle or “diametric” fracture

Displaced fracture of medial portion of both pubic rami

Known as a “straddle” fracture

4

4

Specific sites of fracture-disruption in adults

Pubic bones

Inferior ramus

Superior ramus

Body of pubis

Iliac bone

Stable fracture – periphery of iliac wing (Duverney fracture)

Unstable fractures – iliac fracture extending into

SI joint

Sciatic notch

Acetabulum

Sacrum

Stable – transverse fracture below sciatic notch

Unstable fractures

Sacral ala

Sagittal

U-shaped

5

5

Specific patterns of pelvic disruption in adults

Mechanism of injury

Lateral compression – 65%

Unilateral sacral alae and bilateral pubic rami

Anterior compression – 15%

Disruption of symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints

Also known as open book injury or sprung pelvis

Vertical shear – 10%

Double vertical ipsilateral fractures of pelvic ring

Also known as Malgaigne fx

Complex – ± 10%

Windswept

Not readily classified

Often include an acetabular component

Best classified as complex acetabular fractures

Classification of pelvic fx

Tile Comprehensive

Young-Burgess

6

6

Specific patterns of acetabular fractures in adults

Acetabular anatomy

Anterior and posterior columns of acetabulum

Posterior wall of acetabulum

Acetabular fossa, labrum, and notch

Sciatic buttress

Judet-Letournel classification of acetabular fractures

Common patterns of acetabular fracture

Transverse

T-shaped

Both column

Transverse with posterior wall

Isolated posterior wall

7

7

Common sites of fractures in the elderly

Insufficiency fractures

Sacrum

Body of pubis

Pubic rami

Supraacetabular iliac

“Fall, rule-out hip fracture” – look for hip fracture mimics in pelvis

Transverse acetabular fracture

Pubic rami fracture

Iliac wing – Duverney fracture

8

8

Common sites of fractures in children and adolescents

Pubic rami

Iliac wing

Double arch fractures

Epiphyseal separation of triradiate cartilage – acetabulum

Apophyseal avulsion

Anterior inferior iliac spine– sartorius

Anterior inferior iliac spine – rectus femoris

Ischial tuberosity – hamstrings

Iliac crest – abdominal obliques

9

9

Injuries likely to be missed

Pelvic rami buckle and “ring” fractures

Posterior wall of acetabulum – undisplaced fracture

Distortion or nondisplaced fractures of sacral foraminal lines, evidence of sacral ala fracture

U-shaped fracture of sacrum

10

10

Where else to look when you see something obvious

| Obvious | Look for |

|---|---|

| In general | |

| Fx in anterior pelvic arch | Fx in posterior pelvic arch |

| Or vice versa | |

| Fx in posterior pelvic arch | Fx in anterior pelvic arch |

| Specifically | |

| Pubic rami fracture | Fracture other ipsilateral ramus |

| Fracture contralateral pubic rami | |

| Fracture ipsilateral or contralateral sacral ala | |

| Avulsion tranverse process L5 | Unstable pelvic fracture |

| Ipsilateral sacral ala fracture | |

| Ipsilateral SI joint diastasis | |

| Disruption sacral foraminal line | Fracture pubic rami |

| U-shaped fracture of sacrum | |

| Pubic symphysis diastasis | Diastases SI joints |

| Sagittal fracture sacrum (Zone 2 or 3) | |

| Fracture acetabulum | Spur sign = both column fx |

| Disruption of obturator ring = either | |

| Both-column fracture or Transverse T-shaped fracture | |

11

11

Where to look when you see nothing at all

If presented with AP radiograph of pelvis

Determine nature of injuring forces.

If sustained significant injury, CT examination is required.

Re-evaluate radiographic examination looking at the following for evidence of subtle fracture:

Sacral neural foraminal (arcuate) lines

Pubic rami – iliopectineal and ilioischial lines

Width of pubic symphysis and SI joints

Fracture transverse processes of L5 = unstable injury posterior arch

Are iliac crests level?

Posterior rim of acetabulum

Margins of obturator ring

If any question concerning above, obtain full CT examination of pelvis.

If presented with CT examination

If sustained sacral plexus neurologic injury, obtain MRI.

If no visible fracture or dislocation but has significant pain or inability to bear weight

Obtain MRI to disclose occult fracture.

Pelvis – the Primer

1

1

Imaging assessment

Radiographic examination

AP

Oblique views

Internal oblique (obturator view)

External oblique (iliac view)

Inlet view

Outlet view

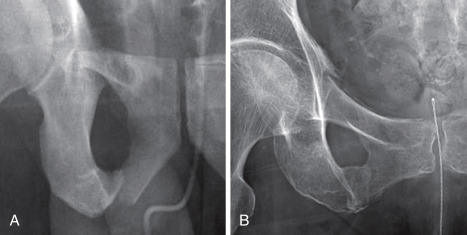

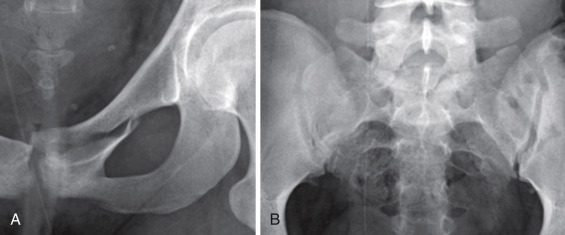

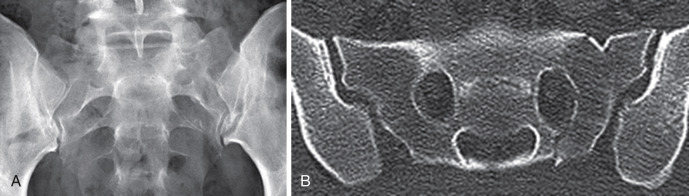

The initial radiograph of those suspected of a pelvic injury is an AP view of the pelvis ( Fig. 8-1 and Fig. 8-2 A ). If severely injured a CT examination (“pan-scan”) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis follows.

If less severely injured an AP view alone or with additional internal oblique, also known as obturator oblique, and external oblique, also known as iliac oblique, views may be ordered. This 68-year-old man was injured in an MVC. Volume-rendered 3-D transparency images simulating radiographic views were obtained: AP, right internal oblique, and right external oblique ( Figs. 8-2 A , 8-2 B , and 8-2 C , respectively). Transverse right acetabular fracture is clearly shown.

Computed tomography (CT)

Axial

Reformatted images

Coronal

Sagittal

3-D

Volume-rendered semitransparent three-dimensional images to simulate radiographic views

- (1.)

AP, inlet, outlet, iliac oblique, obturator oblique

- (2.)

Lateral view of high quality

Not possible to obtain radiographically

- (1.)

Computed tomography (CT) is now the primary modality to evaluate pelvic fractures. Unfortunately, there are no currently accepted guidelines for clinicians in the ordering of pelvic CT examinations such as the NEXUS and Canadian Rules for the cervical spine. There is a need for a similar set of rules for pelvic CT.

Indications for CT

- •

High-energy trauma, as part of chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT (“pan-scan”)

- •

Pelvic or acetabular fracture seen on initial radiograph for full evaluation

- •

Pelvic or hip pain and negative radiographs for detection of occult lesions

Technique

- •

Helical CT is performed without intravenous contrast to include entire pelvis and hip joints.

- •

Scan data are reformatted to 2 mm sections in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes.

- •

Surface-rendered 3-D image of the pelvis to allow scrolling of images in both axial and sagittal rotation

- •

Volume-rendered semitransparent 3-D images using thin overlapping sections to create images that effectively simulate routine radiographic projections (AP, inlet, outlet, iliac and obturator obliques, lateral)

- •

In those with acetabular fractures, the ipsilateral femoral head and contralateral hemipelvis are removed by region of interest (ROI) subtraction to allow for visualization of the surface of acetabulum.

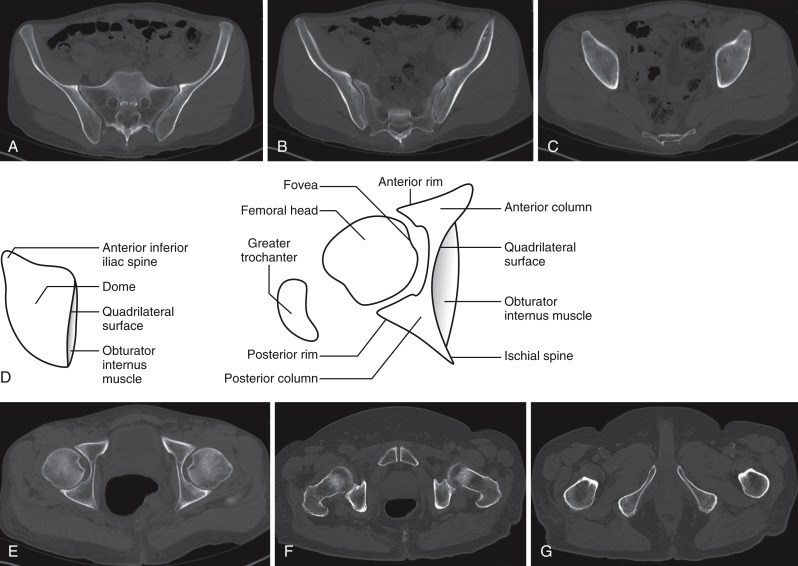

Thin section axial images are obtained through the entire pelvis, from just above the iliac crest to below the pubic rami. Superiorly the upper sacrum and normal sacroiliac SI joints are shown ( Fig. 8-3 A ). Note the normal smooth cortical surface of the left sacral ala and the cortical disruption or fracture of the outer margin of the right sacral ala. The SI joints are intact and well marginated; the widths of the joints are even throughout. A more inferior image shows the normal lower sacrum and SI joints ( Fig. 8-3 B ).

The third axial image ( Fig. 8-3 C ) shows the domes of the acetabuli. A fracture is present in one hip. Which one? A fine oblique fracture line is present in the right acetabular dome with enlargement of the right obturator internus muscle indicative of edema and hemorrhage within the muscle. Compare with the normal left side. The anatomic features of the dome of the acetabulum and hip joint in the axial plane are designated ( Fig. 8-3 D ). Axial image of the hip joints is shown ( Fig. 8-3 E ).

The next lower axial image ( Fig. 8-3 F ) show the symphysis pubis, femoral heads and necks, and posterior inferior aspect of the hip joint. The lowest axial image ( Fig. 8-3 G ) contains the inferior pubic rami and proximal shaft and lesser trochanters of the femurs.

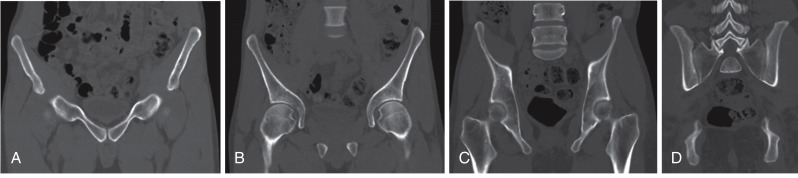

Two-dimensional (2-D) images are reformatted in the coronal and sagittal images through the entire pelvis. The anterior pubic rami and pubic symphysis are seen in the most anterior image ( Fig. 8-4 A ). The next image contains the hip joints ( Fig. 8-4 B ). The third coronal image shows the quadrilateral surface of the inner wall of the acetabulum and the iliac wings ( Fig. 8-4 C ). The upper sacrum, SI joints, and adjacent iliac bone are seen in the fourth coronal image ( Fig. 8-4 D ).

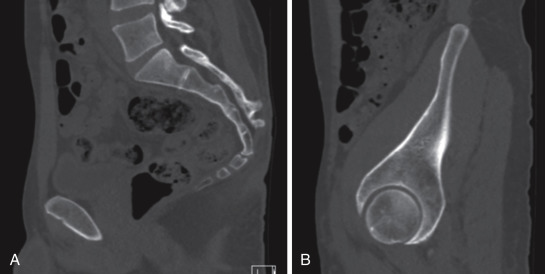

The principal features of the sagittal 2-D images are the midline section of the sacrum ( Fig. 8-5 A ) and sagittal section through the mid-acetabulum ( Fig. 8-5 B ). Fractures of the sacrum are easily overlooked on both plain radiographs and the axial images of a CT examination. It is critical that 2-D sagittal images be reformatted in the CT of every case of significant pelvic trauma to avoid such unfortunate errors and oversights.

Three-dimensional imaging is now immediately available on most CT equipment. There are a variety of potential imaging sequences available, but the most common and most useful for the evaluation of the bony pelvis are surface-rendering and volume-rendering transparencies that mimic radiographic images.

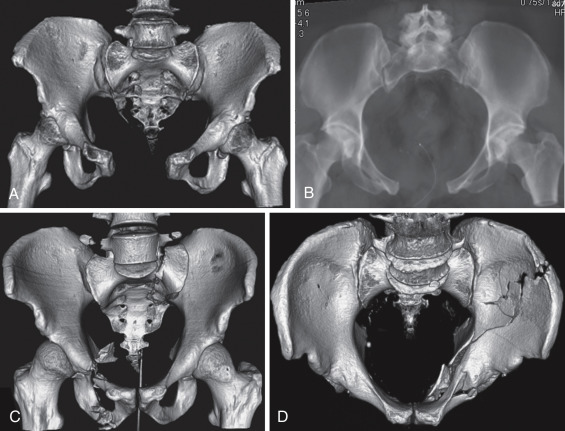

This 54-year-old woman sustained an open book injury of the pelvis in a high-speed MVC. Surface- ( Fig. 8-6 A , AP projection) and volume- ( Fig. 8-6 B , inlet view) rendered CT images of the entire pelvis clearly depict fractures of the right pubic rami and dislocations of the symphysis pubis and bilateral SI joints. The full extent of the injuries is readily apparent.

Surface-rendered 3-D images of two complex injuries of the pelvis are shown. The first ( Fig. 8-6 C ) is a bilateral posterior dislocation of the sacroiliac joints with fractures of the right superior and inferior rami. Note also the bilateral avulsions of the transverse processes of the fifth lumbar vertebra. All injuries are readily identified. The second ( Fig. 8-6 D ) is an inlet projection of a both-column fracture of the left acetabulum. Fractures of the left ilium and disruption of the left obturator ring and acetabulum are obvious.

Three-dimensional imaging should be obtained in every pelvic CT examination for pelvic trauma. Surface-rendered images for scrolling in the axial and sagittal planes allow one to appreciate the full extent of pelvic injuries and are most helpful for treatment planning. Volume-rendered transparencies should be obtained routinely as a substitute for the additional radiographs (inlet, outlet, and obturator and iliac obliques) that are often obtained. Such radiographs take time and effort that the patient’s condition may not allow. Processing the CT database to make 3-D images can be accomplished in a short time and requires no additional examination of the patient.

2

2

Anatomic features

Pelvic ring

Composed of two innominate bones and the sacrum

Joined posteriorly by the two sacroiliac joints

Joined anteriorly by the symphysis pubis

Ring consists of two arches.

The posterior or femorosacral arch extends from one acetabulum to the other.

The main weight-bearing component of the pelvis

The stronger of the two arches

The tie or anterior arch extends inferiorly and anteriorly from each acetabulum.

The weaker arch

Fractures more likely to occur in anterior arch

Pelvic ligaments

Stability of pelvis is dependent on the integrity of strong ligaments.

Posterior and anterior sacroiliac ligaments

Posterior sacroiliac ligaments are strongest ligaments in the body.

Sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments

Extend from the sacrum to the ischial spine and tuberosity

Iliolumbar and iliosacral ligaments

Attach fifth lumbar transverse processes to ilium and sacrum

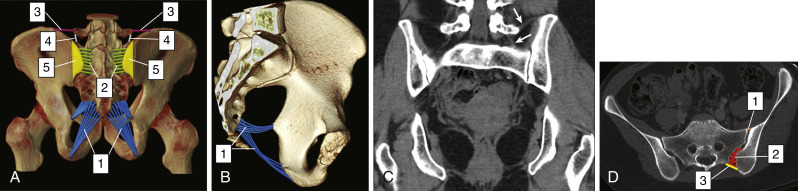

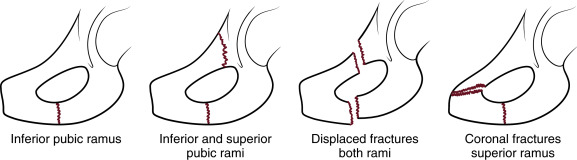

Volume-rendered posterior projection of the pelvis ( Fig. 8-8 A ): pelvic floor ligaments (1), posterior sacroiliac ligaments (2), iliolumbar ligaments (3), lumbosacral ligaments (4), and posterior superior iliac spine (5). Volume-rendered lateral projection of the left hemipelvis ( Fig. 8-8 B ): pelvic floor ligaments (1) run from the inferolateral sacrum to the ischial spine and ischial tuberosity.

Coronal CT image shows iliolumbar (top arrow) and lumbosacral (bottom arrow) ligaments ( Fig. 8-8 C ).

Axial CT image through the sacroiliac joints shows the sacroiliac ligaments: anterior SI ligament (1), interosseous ligament (2), and posterior SI ligament (3) ( Fig. 8-8 D ).

3

3

Stability of fractures variable

Stable fractures

In general

Single fracture limited to either anterior or posterior arch

Most common in anterior arch

Isolated fxs of posterior arch are rare.

Principal pelvic ligaments remain intact.

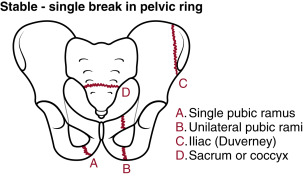

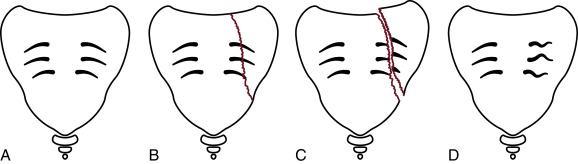

Common stable fractures ( Fig. 8-9 )

Pubic rami

Body of pubis

Iliac – periphery of iliac wing (Duverney fracture)

Sacrum – transverse fracture below sciatic notch

Coccyx

FIGURE 8-9

Coccyx.

Unstable fractures

In general

Fractures involve both anterior and posterior arches.

One or more principal pelvic ligaments disrupted

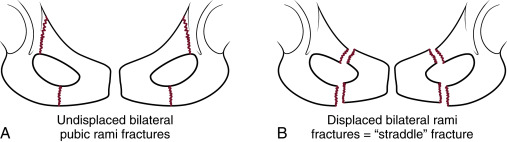

Common types of unstable fractures ( Fig. 8-10 )

Ipsilateral displaced fractures of both anterior and posterior arches

Pelvic dislocation – disruption of pubic symphysis and SI joint or joints

Commonly referred to as an “open book” fracture

Unilateral fractures of pubic rami with sacral ala or iliac fracture opposite side of pelvis

Commonly referred to as a bucket handle or “diametric” fracture

Displaced fracture of medial portion of both pubic rami

Known as a “straddle” fracture

FIGURE 8-10

Straddle fracture.

4

4

Specific sites of fracture-disruption in adults

Pubic bones

Inferior ramus

Superior ramus

Body of pubis

Iliac bone

Stable fracture – periphery of iliac wing (Duverney fracture)

Unstable fractures – iliac fracture extending into

SI joint

Sciatic notch

Acetabulum

Sacrum

Stable – transverse fracture below sciatic notch

Unstable fractures

Sacral ala

Sagittal

U-shaped

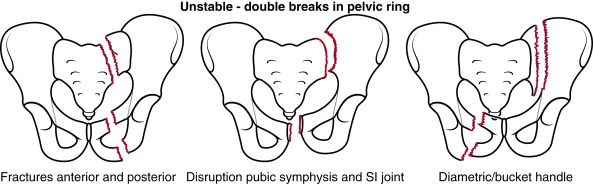

Pubis

Unilateral fractures of an inferior pubic ramus are by far the most common, accounting for over 40% of all pelvic fractures ( Fig. 8-11 ). They are usually located in the medial aspect of the ramus and may extend into the body of the pubis. Approximately one-half of such fractures are accompanied by a fracture of the superior ramus located at the lateral margin of the superior ramus. Superior ramus fractures may extend into the adjacent acetabulum and are then referred to as “puboacetabular” fractures. Such fracture may only be evident on CT examination. The greater the displacement of pubic fractures in the anterior arch, the more likely pelvic instability due to sacral fractures or SI joint disruption in the posterior arch. Coronal orientated pubic fractures indicate lateral compression injuries of the pelvis and are invariably accompanied by fractures in the ipsilateral sacral ala.

Bilateral pubic rami fractures are common and represent a reliable sign of a lateral compression injury of the pelvis ( Fig. 8-12 A ). Their disclosure should prompt a search for accompanying fractures in the posterior arch, particularly fractures of the sacral alae. The more displaced the rami fractures, the more likely concomitant fractures in the sacrum. Direct blows to the body of the pubis or perineum may result in displaced fractures of the pubis consisting of the bodies of the pubic bones, symphysis pubis, and medial portions of the attached rami ( Fig. 8-12 B ). This is known as a “straddle” fracture. The central fragment is usually displaced superiorly and frequently associated with injuries of the urethra or bladder.

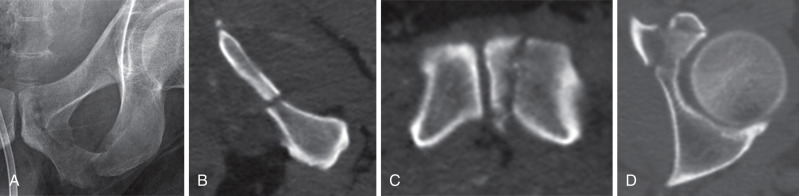

Fractures of both the superior and inferior ramus are shown in Figs. 8-13 A and 8-13 B . The superior ramus fracture is commonly located lateral, at the base of the superior ramus or extends into the anterior acetabulum. The inferior ramus fracture is usually located more medial. The widely displaced fractures of both the superior and inferior right ramus ( Fig. 8-13 A ) were associated with ipsilateral sacral fractures. The minimally displaced fractures of the superior and inferior pubic rami ( Fig. 8-13 B ) were also associated with ipsilateral sacral fractures. Note that the superior ramus fracture extends into the acetabulum, and this type of fracture is sometimes referred to as a puboacetabular fracture ( Fig. 8-13 B ).

Displaced fracture of the inferior pubic ramus and questionable fracture of the body of the pubis are shown on the AP view of the left pubis ( Fig. 8-14 A ). Note the break in the superior cortex of the body of the pubis. CT examination axial images show the typical appearance of a fracture of the inferior pubic ramus ( Fig. 8-14 B ), confirm the presence of the fracture of the body of the pubis ( Fig. 8-14 C ), and disclose an otherwise inapparent “puboacetabular” fracture of the superior pubi ramus ( Fig. 8-14 D ).

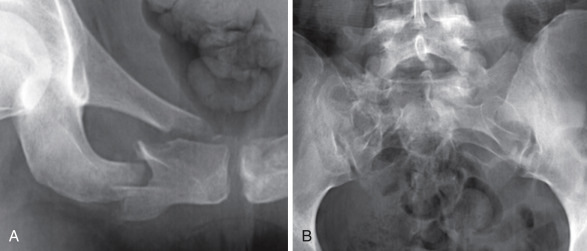

Coronal fractures

Coronal fractures of the superior pubic rami are medial and usually extend into the body of the pubis ( Figs. 8-15 A and 8-16 A ). Such fractures are a clear indication of a lateral compression injury of the pelvis and are invariably associated with fractures of the ipsilateral sacral ala ( Figs 8-15 B and 8-16 B ).

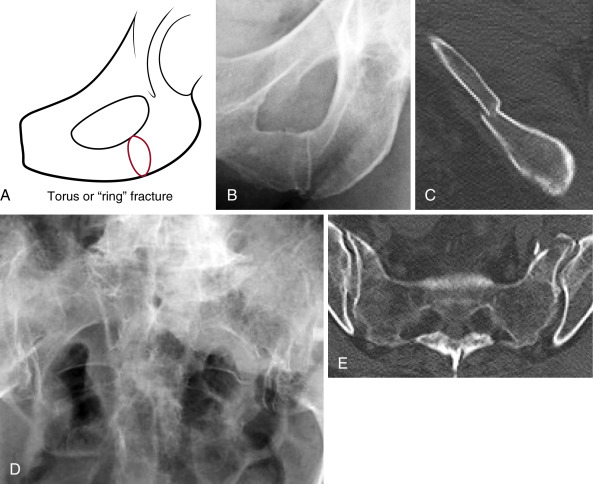

“Ring” fracture

The “ring” fracture of the inferior pubic ramus has a potentially confusing appearance ( Figs. 8-17 A and 8-17 B ), It is often misconstrued as the residuals of an old, well-healed or healing previous fracture on radiographs ( Fig. 8-17 B ), when, in fact, it actually represents a slightly impacted, acute fracture as shown by CT axial image ( Fig. 8-17 C ). The overlap of the cortical margins of the fractures create a sharply defined ring on AP and oblique radiographs ( Fig. 8-17 B ).

This ring-like pubic rami fracture is associated with a left sacral ala fracture from lateral compression injuries of the pelvis. Note the distortion of the upper left sacral foraminal lines on the AP view of the pelvis in this case ( Fig. 8-17 D ). The sacral ala fractures are confirmed by CT. Note the clear depiction of the acute fractures of the left sacral ala on the axial CT image ( Fig. 8-17 E ).

Iliac bone

Stable fracture – periphery of iliac wing (Duverney fracture)

Unstable fractures – iliac fracture extending into

SI joint

Sciatic notch

Acetabulum

Ilium

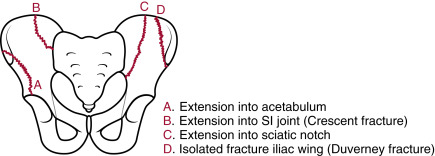

Fractures of the ilium that extend into the acetabulum, SI joint, or sciatic notch are unstable, significant injuries ( Fig. 8-18 ). Therefore, fractures of the iliac wings should be evaluated closely to determine whether or not the fractures extend into the acetabulum, SI joints, or sciatic notch. Such fractures are usually associated with other significant injuries of the pelvis. On the other hand, fractures of the periphery of the iliac wings, referred to as Duverney fractures, are free of such extensions and associated injuries and are therefore considered stable.

Unstable iliac fractures

Fractures of the ilium that disrupt the pelvic ring are unstable. There are three types of such fractures, each of which extends into either the acetabulum or sciatic notch or the SI joint ( Fig. 8-19 ). In the first example, a man injured in a high-speed MVC, a vertical fracture extends from the left posterior superior iliac crest into the left acetabulum ( Fig. 8-19 A ). This is one component of a both-column fracture of the left acetabulum. In the second, a man was ejected in an MVC. Note the comminuted fracture of right iliac bone that extends into the right sciatic notch ( Fig. 8-19 B ). This was associated with a U-shaped fracture of the sacrum with sacral plexus injury.

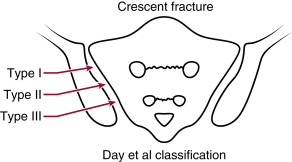

Crescent fracture

The third type of unstable fracture of the ilium is the crescent fracture, a fracture of the ilium that extends into the SI joint and occurs as a component of lateral compression fractures of the pelvis. It is a combination of ligamentous injury of the inferior portion of SI joint and vertical fracture of the posterior ilium that extends thru iliac crest; the posterior superior iliac spine remains attached to the sacrum. The fracture may be stable as the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments remain intact. The Day et al. classification identifies three types, depending upon the point or level at which the iliac fractures enters the SI joint: upper third—type I, middle third— type II, and lower third—type III ( Fig. 8-20 ).

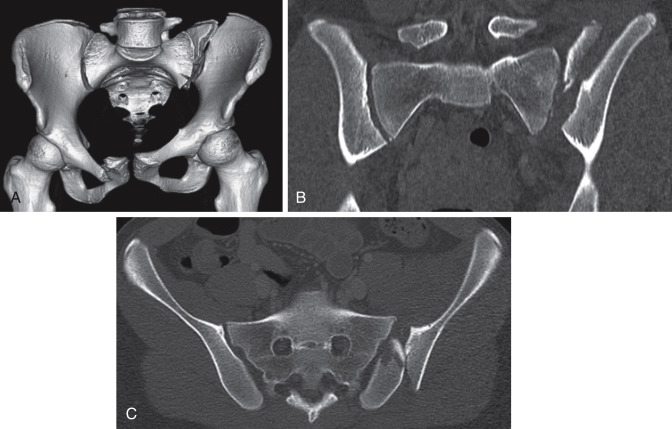

This young man sustained a bucket handle-type fracture of the pelvis in an MVC. Note the fracture of the posterior iliac crest on the 3-D reformatted image ( Fig. 8-21 A ). The fracture extends into the midpoint of the left SI joint, and the inferior half of the SI joint is disrupted, a Day type II. The left hemipelvis is displaced superiorly in keeping with a vertical shearing injury. Pubic fractures are on the contralateral side, indicating a bucket handle-type fracture. Coronal ( Fig. 8-21 B ) and axial CT ( Fig. 8-21 C ) show the SI joint disruption and crescent fracture of the iliac crest. The axial image shows this to be a type II crescent fracture, a fracture into the middle third of the SI joint ( Fig. 8-21 C ), in the Day et al. classification system.

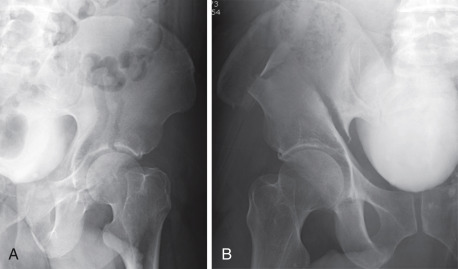

Stable fractures

Isolated fractures of the iliac wing that do not involve the weight-bearing axis of the pelvis are mechanically stable because the pelvic ring remains intact ( Fig. 8-22 ). These are known as Duverney fractures. They may occasionally be associated with significant internal bleeding from the internal iliac system. The fractures otherwise respond well to nonoperative treatment.

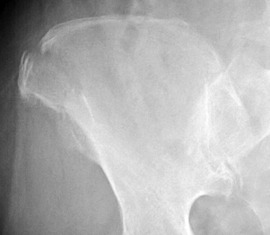

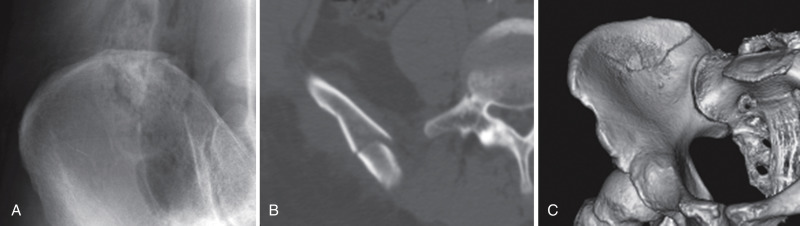

Fractures located posteriorly in the iliac crest may be difficult to see on AP views of the pelvis, as they are obscured by overlying bowel content ( Fig. 8-23 A ). Note the nondisplaced fracture of the iliac crest. This suspected fracture was confirmed by axial CT ( Fig. 8-23 B ) and fully delineated by 3-D reformatting ( Fig. 8-23 C ).

Sacrum

Stable – transverse fracture below sciatic notch

Unstable fractures

Sacral ala

Sagittal

U-shaped

Sacrum

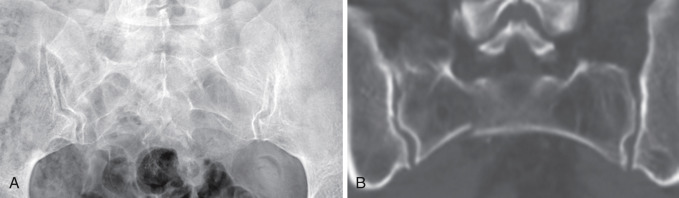

The key to the recognition of sacral fractures on radiographs is the sacral foraminal lines. These fine lines of bone lie over the superior margin of the sacral neural foramina of S1, S2, and S3. On the AP view of the pelvis the sacral foraminal lines of cortical bone are symmetrical side-to-side, fine, smooth, and evenly curved as seen ( Fig. 8-24 A ). The most common injuries in the posterior pelvic arch are sagittally oriented fractures of the sacral alae ( Fig. 8-24 B ) that are identified by disruptions, impactions ( Fig. 8-24 C ), or wrinkled distortions of the sacral foraminal lines without definite disruptions or breaks in the line ( Fig. 8-24 D ).

Unfortunately, the foraminal lines are easily obscured by overlying bowel content, as is often encountered with gastrointestinal ileus following abdominal and pelvic trauma. As a result it is frequently impossible to identify or exclude significant injury on pelvic radiographs ( Fig. 8-25 A ). CT examination is required. Note break in cortex in right ala on coronal CT ( Fig. 8-25 B ).

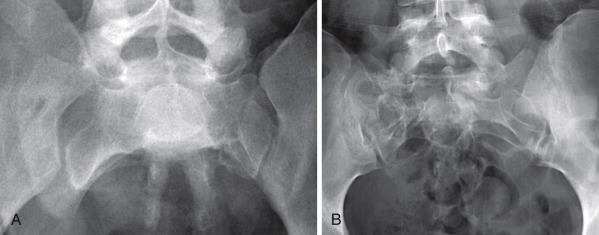

A fracture is readily apparent in the left sacral ala in the case shown below ( Fig. 8-26 A ). Note also that due to compression the width of the left sacral ala is much smaller than the width of the right sacral ala. There is also a dislocation of the right SI joint. At times the sacral ala appear distorted, but there is no distinct fracture line apparent ( Fig. 8-26 B ), as shown in this separate case.

In this case the foraminal lines are seen despite the paralytic ileus pattern of the bowel ( Fig. 8-27 A ). Note the disruption of the upper foraminal line in the left sacral ala that is confirmed by coronal reformatted image from CT ( Fig. 8-27 B ).

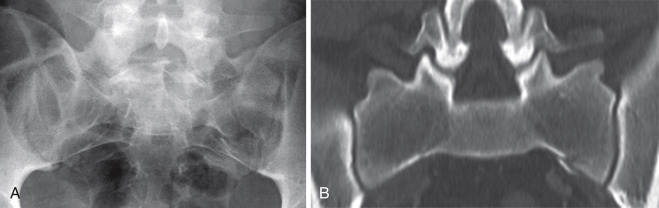

There is distortion and disruption of the left upper sacral foraminal lines and adjacent cortical surface at the SI joint in this case ( Fig. 8-28 A ). These fractures are confirmed by CT, axial image: observe that the fracture of the left sacral ala extends inferiorly into and through the subjacent neural foramen and note also the fracture of the upper cortical surface of the left sacroiliac joint ( Fig. 8-28 B ).

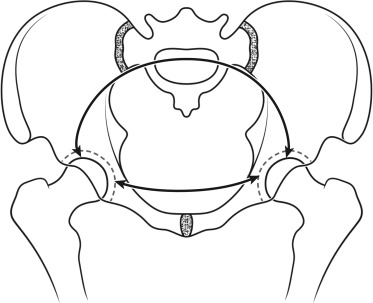

Denis sacral fracture zones

Denis has divided the sacrum into three fracture patterns ( Fig 8-29 ). Zone 1 consists of the sacral ala lateral to the neural foramina; Zone 2 contains the neural foramina; and Zone 3 comprises the midline bone and spinal canal medial to the foramina. The majority of sacral fractures associated with fractures of the pubic bones as described in the Tile classification of pelvic fractures typically involve Denis Zone 1. Five to ten percent of sacral fractures are restricted to Denis Zones 2 and 3. Unlike the majority of sacral fractures contained in the Tile classification those sacral fractures limited to Denis Zones 2 and 3 may occur in the absence of other associated pelvic fractures.