CT is helpful in the diagnosis of endobronchial lesions, hilar and parahilar masses, and hilar vascular lesions.

Technique

In most patients the hila are adequately assessed with spiral CT with a 5-mm slice thickness (it takes about 15 contiguous 5-mm slices to image the hila), but thinner slices are optimal in identifying some findings such as bronchial abnormalities, small lymph nodes, and hilar vessels. Scans with a 1.25-mm thickness are routinely obtained for most chest CT studies and are used in this chapter to illustrate normal anatomy. Contrast medium infusion is optimal for imaging the hila.

Scans are usually viewed with a mean window level of –600 to –700 Hounsfield units (HU) and a window width of 1000 or 1500 HU (lung window) for accurate assessment of hilar contours and bronchial anatomy. Scans are also viewed at a mean window level of 0 to 50 HU and a window width of 400 to 500 HU (soft-tissue or mediastinal window) to obtain information about hilar vessels, lymph nodes, and masses. Both views are necessary.

Diagnosis of Hilar Mass and Lymphadenopathy

A detailed understanding of cross-sectional hilar anatomy is needed to detect and accurately localize hilar abnormalities on CT. Contrast enhancement simplifies the identification of hilar masses and lymph node enlargement.

Lobar and segmental bronchi ( Fig. 5.1 ) are consistently seen on CT and reliably localize successive hilar levels; their identification is key to interpretation of hilar CT. In general, hilar anatomy and contours, at the same bronchial levels, are relatively consistent from one patient to another. Bronchial anatomy and branching is less variable than the branching patterns of arteries or veins.

In some locations, normal hilar silhouettes, visible with a lung window, are consistent enough that a diagnosis of hilar adenopathy or mass can be suggested on the basis of hilar contour alone. In other locations, hilar contours vary according to the size and position of the pulmonary arteries and veins, and contrast opacification of pulmonary vessels is essential for accurate diagnosis.

A hilar mass or lymph node enlargement may be suggested by a local or generalized alteration in hilar contour; a visible mass or lymph node enlargement; bronchial narrowing, obstruction, or displacement; or thickening or obliteration of the walls of bronchi that normally contact the lungs.

As a general rule, any nonvascular (unenhancing) hilar structure larger than 5 to 10 mm (short-axis) should be regarded with suspicion and may represent an enlarged lymph node. However, normal amounts of soft tissue larger than this and representing fat and normal nodes are visible in some hilar regions. Mild lymph node enlargement is commonly present in patients with inflammatory lung disease (e.g., pneumonia), and such lymph node enlargement should not be of great concern. In patients with lung cancer, a lymph node larger than 1 cm should be considered enlarged.

Normal and Abnormal Hilar Anatomy

There are two ways to read hilar CT. The first way is to look at each hilum separately, identifying each important structure, and the second is to compare one side with the other at successive scan levels, looking for points of similarity and difference. It is a good idea to do both.

I suggest that as you read the next section, you first learn about right hilar anatomy, skipping what is written about the left hilum. When you finish, and are somewhat oriented, you should start over, reading about both hila, comparing their anatomy, noting what is symmetric and what is not, and learning how the left hilum differs from the right. Also, you should learn to trace each lobar bronchus from its origin to its segmental branches, because this should be done during interpretation of CT.

Although the hila are not symmetric, they have a number of similarities, and identifying these can be of value. These similarities are emphasized in the following descriptions. To reinforce the normal appearances and their significance, and expected alterations in anatomy occurring because of mass or node enlargement, abnormal findings are discussed for each hilar level described.

Some variation exists among patients in the relative levels of the right and left hila; therefore there is some variation in the levels at which specific right and left hilar structures are visible on CT. The right-to-left relations illustrated in Fig. 5.1 and described in the following text may not be present in individual cases, although side-to-side variation will usually be minor (1 or 2 cm).

Because recognizing lobar and segmental bronchial anatomy is fundamental to interpreting hilar CT, it is reviewed briefly in Table 5.1 . Each of the segments listed is commonly, but not invariably, visible.

| Right Lung | Left Lung | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Lobe | Middle Lobe | Lower Lobe | Upper Lobe | Lower Lobe |

| Apical | Medial | Superior | Apical-posterior | Superior |

| Posterior | Lateral | Anterior | Anterior | Anteromedial |

| Anterior | Medial | Superior lingula | Lateral | |

| Lateral | Inferior lingula | Posterior | ||

| Posterior | ||||

Five levels are reviewed, each localized by the bronchi that are usually visible. These levels are:

- •

upper hila and the right apical and left apical-posterior segments

- •

right upper lobe bronchus and left upper lobe segments

- •

right bronchus intermedius and left upper lobe bronchus

- •

right middle lobe and left lower lobe bronchi

- •

lower lobe bronchi and basal segmental branches

Upper Hila

Right Hilum

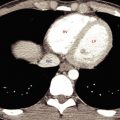

CT at the level of the distal trachea or carina shows the apical segmental bronchus of the right upper lobe in cross section, surrounded by several vessels of similar size ( Fig. 5.2A–B ). On either side a mass or lymphadenopathy is easily recognized. Anything larger than the expected pulmonary vessels is abnormal ( Figs. 5.3 and 5.4 ). Comparison with the opposite side at this level is helpful.

Left Hilum

The apical-posterior segmental bronchus and associated arteries and veins have a similar appearance to the right side at this level ( Fig. 5.2B ), as does lymph node enlargement ( Fig. 5.3A ).

Right Upper Lobe Bronchus and Left Upper Lobe Segments

Right Hilum

Approximately 1 cm distal to the carina, the right upper lobe bronchus is usually visible along its length, with its anterior and posterior segmental branches both generally seen at the same level ( Fig. 5.5A–D ). The anterior segment, usually lying in or near the scan plane, is commonly seen over a length of 1 or 2 cm. The posterior segmental bronchus usually angles slightly cephalad, out of the scan plane, and may not be seen as well. If it is not seen at the level of the upper lobe bronchus, you should look for it at the next higher level. In some normal individuals the origin of the apical segment can be seen at this level as a round lucency, usually at the point of bifurcation (or, in this case, trifurcation) of the right upper lobe bronchus.

Anterior to the right upper lobe bronchus, the truncus anterior (pulmonary artery supplying most of the upper lobe) produces an oval opacity of variable size but often about the same size as the right main bronchus visible at the same level ( Fig. 5.5D ). An upper lobe vein branch (posterior vein), lying in the angle between anterior and posterior segmental branches, is present and is visible in almost all patients. The posterior wall of the right upper lobe bronchus is usually outlined by lung and appears smooth and 2 to 3 mm thick.

Within the anterior right hilum at this level, a mass or lymph node enlargement can be identified if a soft-tissue opacity larger than the expected size of the truncus anterior is visible ( Fig. 5.6 ). This, of course, could be confirmed by contrast medium injection. Laterally, in the angle between the anterior and posterior segmental bronchi, anything larger than the expected vein is abnormal ( Fig. 5.6 ). Posteriorly, thickening of the wall of the upper lobe bronchus or main bronchus ( Fig. 5.7 ) or a focal soft-tissue opacity behind it will almost always be abnormal. An anomalous pulmonary vein branch may sometimes be seen posterior to the bronchus; it is seen at multiple adjacent levels.

Left Hilum

On the left side, at or near this level, the apical-posterior and anterior segmental bronchi of the left upper lobe are usually visible ( Fig. 5.5A–C ). The apical-posterior segment is seen in cross section as a round lucency, whereas the anterior segment is directed anteriorly, roughly in the scan plane, at about the one o’clock position. In some individuals the anterior segmental bronchus is seen at a lower level. These bronchi lie lateral to the main branch of the left pulmonary artery, which produces a large convexity in the posterior hilum at this level, and the superior pulmonary vein, which results in an anterior convexity. In many normal individuals the artery supplying the anterior segment of the upper lobe is seen medial to the anterior segmental bronchus. Lymphadenopathy can be seen in relation to all these structures and is most easily recognized after contrast medium infusion ( Fig. 5.6A and B ).

Right Bronchus Intermedius and Left Upper Lobe Bronchus

Right Hilum

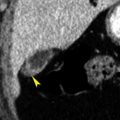

Below the level of the right upper lobe bronchus, the bronchus intermedius is visible as an oval lucency at several adjacent levels ( Fig. 5.8 ). Its posterior wall is sharply outlined by lung. Anterior and lateral to the bronchus, the hilar silhouette may differ in appearance, primarily because of variations in the sizes and positions of pulmonary veins. A collection of fat and normal-sized nodes, sometimes measuring more than 10 mm in diameter, is commonly seen at the level of the bifurcation of the right pulmonary artery, anterior and lateral to the bronchus intermedius ( Fig. 5.8 ). A mass involving the posterior hilum can be readily diagnosed without contrast medium injection because of thickening of the posterior bronchial wall ( Fig. 5.7 ); thickening of the posterior wall of the bronchus intermedius is a common finding in patients with a right hilar mass, particularly when it results from lung cancer.

Diagnosis of anterior or lateral hilar masses at this level generally requires contrast medium administration ( Figs. 5.9 and 5.10 ). Normal soft tissue and nodes ( Fig. 5.8 ) should not be mistaken for a hilar mass.

Left Hilum

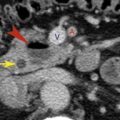

The left upper lobe bronchus is usually visible at the level of the bronchus intermedius on the right. It is typically seen along its axis, extending anteriorly and laterally from its origin at an angle of 10 to 30 degrees ( Fig. 5.8 ). The apical-posterior and anterior segmental bronchi of the left upper lobe usually arise from a common trunk that originates from the upper aspect of right upper lobe bronchus. The left superior pulmonary veins are anterior and medial to the left upper lobe bronchus at this level, and the descending branch of the left pulmonary artery forms an oval soft-tissue opacity posterior and lateral to it. Normal lymph nodes (<5 mm in diameter) are commonly visible medial to the artery and lateral to the bronchus. Because only the oval artery occupies the lateral hilum, lobulation of the lateral hilum (more than one convexity) indicates a mass or lymphadenopathy ( Figs. 5.9–5.11 ).

Although the lung contacts and sharply outlines the posterior wall of the bronchus intermedius at several levels, the left posterior bronchial wall is usually outlined by the lung only at this level; that is, at the level of the left upper lobe bronchus. In approximately 90% of individuals the lung sharply outlines the posterior wall of the left main or upper lobe bronchus, medial to the descending pulmonary artery ( Figs. 5.8 and 5.12B and C ); this is termed the left retrobronchial stripe. As on the right, the bronchial wall should measure 2 to 3 mm in thickness. Thickening of this stripe, or a focal soft-tissue opacity behind it, indicates lymph node enlargement or bronchial wall thickening ( Figs. 5.9 and 5.11 ). In 10% of normal individuals, however, the lung does not contact the bronchial wall because the descending pulmonary artery is medially positioned against the aorta. This should not be misinterpreted as abnormal.

Usually the lingular bronchus is also seen on the left at the level of the bronchus intermedius ( Fig. 5.12 ). The lingular bronchus is usually visible at a level near the undersurface of the left upper lobe bronchus, from which it originates; its two segments (superior and inferior) can sometimes be seen ( Fig. 5.12 ). The superior segmental bronchus of the lower lobe is often visible at this level, arising posteriorly. The pulmonary artery and veins appear the same as at the level of the left upper lobe bronchus ( Fig. 5.8 ). Normal lymph nodes are commonly visible medial to the artery. At this level, significant lobulation of the lateral hilar contour indicates a mass or adenopathy ( Fig. 5.13 ).

Right Middle Lobe Bronchus and Left Lower Lobe Bronchus

Right Hilum

On the right, at the level of the lower bronchus intermedius, the middle lobe bronchus arises anteriorly and extends anteriorly, laterally, and inferiorly at an angle of about 30 to 45 degrees ( Fig. 5.14 ). Because of its obliquity, only a short segment of its lumen is visible at each level on CT, and this appearance should not be misinterpreted as bronchial obstruction. Often the superior segmental bronchus of the lower lobe arises posterolaterally at this level ( Fig. 5.14 ).

At the level of the origin of the middle lobe bronchus, the superior pulmonary veins lie anterior and medial to the bronchus, whereas the descending (interlobar) branch of the right pulmonary artery lies beside and behind it ( Fig. 5.12 ). Normal lymph nodes (<5 mm in diameter) are commonly visible lateral to the artery and bronchus. Because of this separation of the artery and veins, the lateral hilum at this level (representing the artery) is oval, without prominent lobulation. Any lobulation of significant size suggests hilar adenopathy or a mass ( Figs. 5.15–5.17 ).