Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

113 U.S. Supreme Court 2786 (1993) (1, 2)

Introduction

The traditional role of the diagnostic radiologist to supervise, evaluate, and reach conclusions regarding imaging examinations is generally performed with a sense of confidence, based on experience and a reasonable familiarity with the medical literature. When radiologists identify abnormalities in cases of suspected physical child abuse, they may be drawn from their relatively sheltered world of diagnostic imaging into a potentially daunting realm of child protection/welfare agents, law enforcement officers, and representatives of the courts (3–11). Because allegations of child abuse usually focus on the injured child’s caretakers, the customary relationship between the radiologist and the patient’s family may be fundamentally altered. In this sensitive area where a thorough and methodical imaging analysis is essential, the radiologist may be hampered by anxieties over involvement with societal institutions that function to protect the welfare of the child and to identify and prosecute individuals responsible for the injuries.

The three preceding chapters have described the societal context in which the radiologist dealing with cases of suspected child abuse must function. The goal has been to give factual information and guidance regarding the legalities in cases of alleged abuse. In this chapter, I would like to provide a personal perspective based on a career operating in this challenging arena. The opinions presented here reflect my own experiences and observations and are by no means applicable to all individuals and situations. The vagaries of individual cases and wide variations in legal processes from civil to criminal matters as well as region to region preclude a rigid set of recommendations. It is hoped that readers will seriously consider the views expressed here and, on the basis of their own experience and practice setting, develop a systematic approach that preserves his or her unique professional perspective, thereby serving the interests of the child and the judicial process. Radiologists must recognize the limitations imposed by their formal training and experience. Although imaging may be central to the diagnosis of abuse, the radiologist must refrain from delving too deeply into medical issues unrelated to diagnostic imaging and should avoid the role of amateur investigator. With a little experience, the radiologist may develop a false sense of security, and even a cavalier attitude, which may pose hazards to all concerned. As radiologists become more focused about the courtroom, they can be distracted from the reading room, the place where the fundamental and critical elements of the diagnostic process are centered.

The radiology report

The diagnosis of abuse is frequently unsuspected when injured children present for medical attention, and the radiologist may have no indication that abuse is a concern. Because maltreated infants and young children may have made prior visits to a physician’s office or emergency department before the correct diagnosis is considered, abuse may not initially enter the radiologist’s differential diagnosis. The dictation will simply describe the imaging findings and a customary radiology report will be generated.

When the radiologist is the first to suspect abuse on the basis of the specific radiologic abnormalities, or apparent inconsistency between the history provided and an imaging alteration, the report may undergo considerable scrutiny and could become evidence in civil and criminal proceedings. Therefore, the report should be constructed in a manner that provides a systematic delineation of the abnormalities present and a conclusion which is justified on the basis of these findings, and when appropriate, correlated with the results of other diagnostic studies, clinical assessments, and historical data.

In many instances, when a localized nonspecific abnormality is encountered during an examination of a particular anatomic region, the report may not differ significantly from a conventional report. With other examinations, such as skeletal surveys, the report must be more detailed and carefully constructed than usual. Each fracture must be described with respect to precise location, position of fragments, and estimated age. Any errors in this analysis may well be recognized in the courtroom, and what may be an innocent and understandable oversight can be used to impeach the otherwise reliable testimony of a credible witness. When widespread osseous injuries are encountered in young children, a precise reporting of the number of injuries, their exact location, patterns, and ages can be challenging to structure in purely free text form. Even when the various injuries are accurately described and enumerated, it may be difficult for other physicians to extract the data from the report and replicate it in their own documents. Other radiologists interpreting corroborative studies and those reading follow-up surveys may find it problematic to achieve a precise correlation of the comparative studies. Nonmedical investigating agents may be confused by the magnitude and complexity of the reported findings. A data entry module using a series of drop-down menus minimizes these difficulties and provides a documentation of the injuries that can be used in subsequent legal proceedings (12).

A question often arises as to just how far radiologists should go in suggesting, or in fact making the diagnosis of abuse. Views on this subject vary, but I believe it is usually inadvisable to assert a diagnosis of abuse in a report when the radiologic features alone do not provide a confident diagnosis. When the diagnosis of abuse rests on nonspecific alterations that are inconsistent with the history provided on the x-ray requisition, it is prudent to exercise particular caution in the wording of the report. Although abuse should be suspected by primary care physicians when the history provided directly to them by caretakers is inconsistent with the witnessed injury; a history given on a radiology requisition cannot be reliably viewed in the same manner. At most, an indication that “the radiologic abnormality noted would be unusual given the history provided” should be acknowledged. When no history of trauma is given in the face of a gross traumatic finding, this should raise greater concerns and prompt a statement that additional imaging studies may be appropriate. Most importantly, the radiologist should communicate directly with the appropriate clinician to ascertain the specifics of the traumatic event, the physical examination, and any other pertinent medical history. After these communications, when strong indicators of abuse are identified, it may be appropriate to raise the possibility of abuse in the report. It is also advisable to document in the report that such discussions have occurred (13).

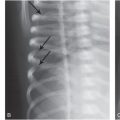

When high-specificity indicators such as the classic metaphyseal lesion (CML) and rib fractures (particularly posteromedial) (see Chapters 2–5, and 21) are identified in an otherwise normal infant, the radiologist may have the responsibility to raise the issue of abuse in the report. The use of terms such as “concerning for,” “consistent with,” “compatible with,” “characteristic of,” or “indicative of,” a diagnosis of abuse/inflicted injury may be justified. When the initial radiologic findings are inconclusive or point to abnormalities involving other sites or systems not encompassed in the examination, additional studies should be recommended.

The final report should be read carefully before being signed. In complex cases in which multiple injuries are present, it may be useful to review the images, original “wet readings”, or other notes on the case before finalizing the radiology report. In a work flow that increasingly emphasizes productivity, there may be a tendency to finalize a report immediately following completion. Since apparent or real errors, inconsistencies, and ambiguities requiring addenda can take on special significance in medico-legal matters, it is advisable to initially place these reports into a draft or preliminary status. The report, along with all appropriate imaging, can be revisited and necessary modifications can be made before finalization. With important movements toward greater transparency and access to hospital records via patient portals, this step cannot be overemphasized.

It should be remembered that a significant suspicion of child abuse requires a report to a child protection agency, and a mandated reporter may be exposed to civil and criminal liability for failure to report abuse (4). The radiologist’s role in this process is covered in Chapter 25.

Discussions with parents

This subject has also been covered in Chapter 24, but a few points should be emphasized. The issues surrounding cases of suspected abuse are frequently of great interest and concern to parents and guardians. Discussions between the radiologists and these parties regarding the findings of imaging studies are generally inadvisable. Information is best communicated by primary care physicians and consultants who have established a relationship with the family and possess the necessary background information and skills to discuss the imaging findings in the clinical context. Child Abuse Pediatricians can have a particularly positive influence on this exchange of information. These subspecialists are best suited to bring together all the relevant data and present it to the parents/caretakers in a fully informed, sensitive, and nonjudgmental manner. Although it may seem an easy task, even a professional responsibility, to provide the family with a simple description of the abnormalities encountered, offering this information can lead to additional questions that are best handled by professionals skilled in these unique interactions. Because parents are usually anxious to hear the results of the studies, it is essential to communicate immediately with the responsible clinicians so that the family’s concerns can be addressed in a timely manner.

Contacts with investigators

Within days of a report of suspected abuse, the radiologist may be contacted by a representative of child welfare/protective services or a law enforcement agency. In some instances, particularly in cases of suspected homicide, a district attorney may request information. When the inquiry comes via telephone, it is essential to get the full name and position of the caller. When there is doubt as to the authenticity of the inquiry, it may be useful to obtain a telephone number where the call can be returned and the reliability of the inquiry established. It is not unusual for telephone contacts to be made when the investigator has only sketchy information regarding the radiologic findings. Because authorized investigators usually have access to the medical record, it is reasonable to expect that the callers have copies of all pertinent radiologic reports before any substantive discussions ensue. This will minimize confusion and also expedite these conversations. The radiologist should be aware that investigators generally take notes during interviews, and these notes, accurate or not, may find their way into documents that are eventually submitted to the courts.

It must also be stressed that a great range of medical knowledge and experience can be expected among child welfare/protective service workers, police investigators, and attorneys. They may not fully understand or may misconstrue information that seems quite straightforward to the radiologist. It is important that the radiologist assesses the level of understanding of the interviewer and, if necessary, take time to instruct the caller about the relevant issues underlying the radiologic findings. On occasion, it may be advisable to recommend termination of the conversation, suggesting that the interviewer read some recommended references in order to acquire the background information necessary to grasp the issues at hand.

It is wise to document all telephone conversations and interviews that have taken place regarding specific cases. A simple computerized database can be set up in which all inquiries are logged along with the time, date, and names of the caller and patient under discussion. The general topics covered during the discussion are described, but the details of the conversation need not be included.

Precautionary measures

Most pediatric radiologists with extensive experience in the area of child abuse have their horror stories of events that could have been avoided if they had been more aware of the peculiarities of this special realm. Although it is not possible to anticipate all situations, some general precautionary measures can be taken.

A radiologist with an interest in abuse may be shown or sent images from colleagues in cases of suspected abuse. These images are often suboptimal in quality and may not represent the entire series of images obtained in the patient. Clinical information is often incomplete and sometimes incorrect. These cases are often sent because they are controversial, and the outside consultation is designed to support a particular point of view or to resolve a controversy. It is obvious that the radiologist may be entering hazardous territory and must exercise caution in providing an opinion. Sometimes these efforts to seek help take the form of “curbside” consults. The consultant may view low-resolution images on a desktop or laptop computer with a standard display (or even a smartphone!) and be tempted to draw a conclusion in a manner that would never occur with a patient in the radiologist’s own department. I have personally been threatened with a subpoena to attest to a radiologic interpretation that I allegedly made after a cursory review of images shown to me at a medical meeting.

The practice of requesting advice from colleagues is an important one, but it is important to apprise the requester of any potential limitations to your observations/opinions at the outset. When cases are sent by a colleague to a radiologist for review, it is likely that other professionals involved in the case are aware that this consultation will occur. Unless the radiologist is rendering a written report on the case, it is wise to make clear that the opinion is an informal one, designed to assist the referring physician in their interpretation of the findings, and that the consulting radiologist explicitly wishes to be excluded from any possible involvement in the case.

Once the diagnosis is made

When radiologic studies specifically point to abuse, or when nonspecific radiologic findings in conjunction with other clinical and laboratory data suggest abuse, the radiologist’s involvement in the diagnostic process may not be over. Further radiologic studies may be indicated, not only in the patient, but in other children at risk, such as infant siblings.

Although the fundamental approach to diagnosis in cases of abuse is similar to that for other pathologic conditions, there is a practical difference. In accumulating data that support a particular diagnosis, the radiologist need only produce sufficient imaging findings to reasonably justify the diagnosis on medical grounds. Criteria for diagnosis are usually straightforward, and there is a general consensus as to how much data are required to proceed with therapeutic measures. However, what may represent sufficient imaging evidence to indicate child abuse on medical grounds may fall short of that needed to convince other professionals or jurors that abuse has occurred. In some instances, this may reflect ignorance on the part of investigative and legal authorities regarding what constitutes the medical diagnosis of abuse. In other situations, the adversarial nature of the court system may demand that additional indications of abuse are needed to meet the legal standard. Most pediatric radiologists with experience in the courtroom have been frustrated by cases in which the medical evidence obviously indicated abuse but the diagnosis was ultimately rejected by the judge or jury. The fact that a radiologist expresses the opinion that abuse has occurred does not make it true in the judgment of the court or jury, particularly if other medical experts disagree.

It is unwise to end the radiologic assessment simply because the medical diagnosis of abuse is made; rather, it is prudent to perform those studies that fully determine the number of injuries, their characteristics, and their ages as described in the preceding chapters. Another reason for performing additional studies once the diagnosis is made is that the diagnostic process is imperfect. As physicians, we are trained to offer opinions that are generally correct to a level of certainty required for patient management. However, as with all other aspects of radiologic practice, errors are made. It is, therefore, prudent for the radiologist to maintain a certain degree of humility in the process, showing a willingness to alter impressions where appropriate. The radiologist should be willing to take a second look at the imaging data, particularly in light of any new information, and to perform additional studies when demanded by the situation.

The subpoena

One of the most unnerving events for radiologists inexperienced with the courtroom is the unannounced delivery of a subpoena demanding an appearance in a court proceeding involving child abuse. The case may be recent and familiar, or the child’s name may be unrecognizable. The subpoena may elicit both anger (“Why me?”) and fear (“I’ve never done this before!”). Both responses are understandable. Subpoenas are a routine and effective means of notifying prospective witnesses that their presence may be required to shed light on certain matters in civil and criminal cases of alleged child abuse (see Chapters 25 and 26). The radiologist may be able to provide critical information in these cases that assists in determinations affecting the welfare of the child and possible criminal prosecution. Most subpoenas indicate the lawyer responsible for the summons and provide a telephone contact. A phone call to the attorney will clarify the reason for the subpoena. In some cases, subpoenas are issued to virtually all the physicians with any knowledge of the case. During discussions with the attorney, it may become obvious, in view of the lack of any pertinent imaging studies, that there is no need for a radiologist to testify. In other instances, when multiple radiologists from the same institution have been served a subpoena for the case, only one may actually be needed to provide court testimony.

Subpoenas may arrive within days of the required appearance, often conflicting with the radiologist’s schedule. Although the date stated may well be the date the court proceeding is scheduled to begin, it is not necessarily the day that the radiologist will be expected to appear. Trial dates are frequently postponed, and it is not unusual for several continuances to be granted until the trial finally takes place. For the physician who frequently encounters cases of child abuse, it is common to have a calendar full of trial dates that are repeatedly postponed and rescheduled. In many instances, cases may be settled without a trial and the radiologist will never have to appear. It is therefore wise to refresh one’s memory regarding the general aspects of a case upon receipt of a subpoena, but to reserve a detailed review of the case and preparation for testimony until a few days or weeks before the scheduled courtroom appearance.

Preparation for court

As the court date approaches, a review of the radiographs and other pertinent data should be followed by a face-to-face meeting with the requesting attorney. This important pre-trial conference is necessary to ensure that the radiologist’s testimony is provided in an organized and comprehensible manner. The subjects covered during this pre-trial conference have been covered in detail in Chapter 26, but it should be emphasized that this is not only an opportunity for the lawyer to explain what should be expected in the courtroom, but also a chance to educate the attorney regarding the medical issues involved in cases of child abuse. It may be advisable to give the attorney pertinent references on the subject, as well as to discuss controversial areas that may be addressed on cross-examination. In this pre-trial conference, the lawyers generally indicate which areas of the medical record they would like to cover during their questioning. Often the lawyer’s planned areas of inquiry may extend outside the expertise of the radiologist. Radiologists should indicate what issues they are comfortable with and which ones fall outside their knowledge and experience. In general, they should exercise caution in straying beyond those areas that do not relate to diagnostic imaging.

During this meeting, the date of trial testimony can be tentatively arranged. Most attorneys are willing to accommodate a physician’s schedule when testimony is required. In care and protection cases, in which hearings frequently last less than a day, the lawyers are often able to arrange for an appearance date that is convenient for the radiologist. In criminal proceedings, in which a trial may last days or weeks, the attorney will often arrange for an appearance on a day that fits the radiologist’s schedule. Unfortunately, unexpected delays and schedule changes do occur, particularly in criminal cases, and they may entail a long wait outside the courtroom. It is often advantageous to be scheduled as the first witness of the day; in the event of a change in the schedule, the radiologist can be notified the day or evening before the trial. When the site of the trial is near the physician’s institution, it may be possible to put the radiologist “on-call” and to advise proceeding to the courthouse upon notification. In general, judges attempt to accommodate medical witnesses, particularly when the latter have had direct involvement with the case.

Preparation for testimony

This subject has been covered in depth in Chapter 26. The radiologist should have copies of all the imaging reports, and, at a minimum, should have a general outline of the clinical aspects of the case. If the radiologist has reviewed documents and clinical records pertaining to the case, these may be the subject of intense inquiry under oath. Child abuse cases are often complex and the medical records voluminous. It is the author’s practice to review those records that provide a reasonable basis for assessment of the radiologic aspects of the case. In general, the courts are interested in the radiologist’s opinion with respect specifically to those medical issues bearing upon the imaging studies. The exception may be the expert who is “used” by an attorney because he or she is willing to stray well beyond their areas of radiologic training and expertise, delving into issues that are more appropriately addressed by other medical specialists.

Courtroom testimony

As with all physicians, radiologists must adhere to the highest standards of professional conduct when engaged as witnesses in a court proceeding. Many professional societies have policies/standards that define these responsibilities, often focusing on testimony in malpractice cases. Other authors have addressed the issues of physician professional conduct when giving court testimony (5, 6, 14–21). Although cases of alleged child maltreatment have unique medical elements, the general principles defined in these documents apply to testimony in cases of child abuse. Other authorities have addressed the specific issues of irresponsible medical testimony in this context (3, 10, 21–31).

Care and protection cases

When called to testify in family court in a care and protection case entailing alleged abuse, the radiologist can generally expect a less formal proceeding than in a criminal case. The goal is to arrive at a decision in the best interest of the child, rather than to determine the guilt or innocence of a specific party. In most instances, the burden of proof is to demonstrate that it is more likely than not that the child has suffered abuse. The radiologist’s role in these proceedings may be as much an educator as a witness. Judges are generally anxious to have the radiologist explain the scientific basis for their opinion, and often give the expert wide latitude in providing background information on which an understanding of the child’s injuries can be based.

Although there is an adversarial element to the civil court proceeding, radiologists should be comforted that their customary role of physician is generally similar to that of the presiding judge – to protect the well-being of the child in question. The Honorable Mr. Justice Wall has summarized this issue with clarity, indicating that “the issue and the litigation is not whether one party or the other succeeds in achieving their ends; its objective is to achieve the result which is for the optimal benefit or least detriment for the child” (9). In my experience, care and protection proceedings have become somewhat more contentious and adversarial in recent years, and on occasion the proceedings may resemble or even be more charged than some criminal trials.

Criminal cases

In contrast to civil proceedings, criminal trials are conducted with greater formality and strict adherence to legal procedure and decorum. For a variety of reasons, cases may be highly publicized and the legal proceedings televised. Even experienced radiologists may suffer considerable anxiety in advance of their court appearance. Because the imaging findings may form the basis of a determination of physical abuse, the radiologist’s testimony may be heralded with considerable interest by all parties to the case. This anticipatory climate may be palpable as the radiologist takes the stand and can in fact influence their composure and demeanor. I recall the first occasion that I had to give testimony in a murder trial. After being called to the witness stand, I walked by several people seated in the gallery, and as I passed by one of the defendant’s family, I noticed that half his face was covered with tattoos. Needless to say, this observation did little to allay the apprehension that had evolved over the preceding sleepless night. Some anxiety should be expected when a radiologist has to offer testimony that may contribute to a verdict that means either incarceration or freedom for the defendant. I have often thought that if I am ever entirely comfortable with the role of expert witness in a criminal proceeding, it may be time to reassess my professional priorities.

Points to keep in mind

What the radiologist can expect in court has been discussed in detail in Chapter 26. A number of points should be emphasized and are summarized below.

Courtroom strategy

Physicians with extensive experience in the courtroom may readily offer courtroom strategies to their colleagues that focus on how to deal with an aggressive cross-examination. Courtroom strategy, in the customary sense, should be left to lawyers. If physicians are concerned that their testimony may be damaged or their credibility undermined in the courtroom, they need to look harder at the imaging data and the conclusions they have reached. If the radiologist is uncertain that his or her conclusions are justified, this uncertainty should be shared with the court. When the radiologist is confident about a particular point of testimony, this should be stated with certainty. A thorough familiarity with the imaging findings and the pertinent literature that support the radiologist’s opinion is far more important than any courtroom strategy the witness might employ. In general, increased experience will bring greater comfort and effectiveness in giving testimony. A preoccupation with legal technique may divert the radiologist from the fundamental role of providing fact and opinion that may bear on case outcome.

Use of charts and diagrams

Anatomic diagrams depicting the sites of injury are valuable tools in the courtroom. When multiple fractures are present, the use of a diagram to delineate and tabulate the fractures is generally well received by the jury. Although demonstration of fractures and other abnormalities using the actual imaging studies is of value, the injuries may not be adequately displayed in the courtroom setting. In such instances, a diagram displaying all lesions may give the judge/jury a better overview of the extent of inflicted injuries. Once the specific injuries have been presented, the jury can be taken one step further in understanding the nature of the assaults by being shown a diagram depicting the presumed mechanism of injury. This is particularly useful with respect to posterior rib fractures where a mechanism of thoracic compression in the anteroposterior plane is generally accepted (see Chapter 5). Most textbooks on the subject of trauma include diagrams designed to facilitate an understanding of accidental injuries, and similar illustrative material should be accorded the jury in child abuse cases.

Avoid bias

There may be a tendency to view the case through the eyes of the parties who have requested the radiologist to appear in court. The radiologist must make every effort to provide facts and opinions that would be essentially the same regardless of which side calls the witness to testify. One recent study suggests that this may not be the case (30). Bias is a fact of life, but the radiologist-witness has a responsibility to reach conclusions that are formed primarily on the basis of the imaging findings.

Respect the jury

When radiologists are permitted to give background information to the court regarding physical injury to children, most jurors are able to understand the critical elements of the medical testimony. The radiologist should speak slowly and clearly, using lay terminology whenever possible, and when technical terms must be used, they should be defined for the jury. This will ensure that the testimony is understood, and the jury may well accord the radiologist greater credibility because of the respect they have been shown by the witness.

Conclusion

In recent years, the legal community has gained increased sophistication regarding the features of child abuse and its imitators. The critical legal arguments relating to the radiologic testimony are likely to deal more with whether or not abuse has occurred, rather than with who is responsible for the injuries. A “battle of experts” may ensue and a verdict may rest on which expert’s testimony is believed. Whether radiologists testify for the prosecution or the defense, their opinions will be accepted in some cases and rejected in others. It is understandable that an expert may hope that a case is decided in a particular way, and disappointment may follow the “wrong” verdict delivered by the jury. If radiologists are to contribute to the judicial process, they must understand and attempt to respect the legal system. Rather than focusing on the outcome of the case, their goal should be to provide facts and opinions in a clear and concise manner that the judge and jury can carefully weigh in light of all other testimony. The radiologist with an interest in child abuse is a valuable resource for the courts, and the focus should be on the provision of reliable and informed court testimony rather than on a particular legal outcome.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree