Chapter 14 The sacroiliac joint

This effect can be modelled by holding a pretzel in two hands and twisting it around its long axis in alternating directions. Eventually the pretzel will snap. The same occurs clinically. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum occur in elderly individuals, particularly females, in whom the sacroiliac joint is relatively ankylosed and in whom the sacrum has been weakened by osteoporosis. Under these conditions the torsional stresses, normally buffered by the sacroiliac joint, are transferred to the sacrum, which fails by fracture. Conspicuously and strikingly, these fractures run vertically through the ala of the sacrum parallel to the sacroiliac joint.1–8

Structure

Bones

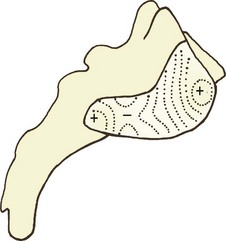

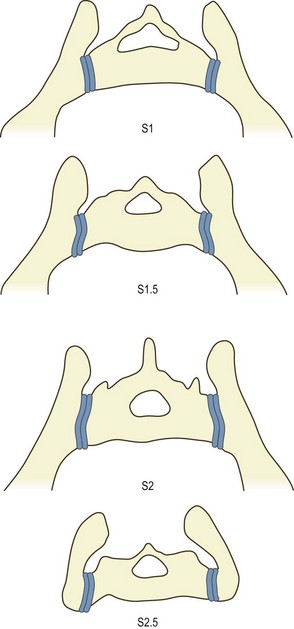

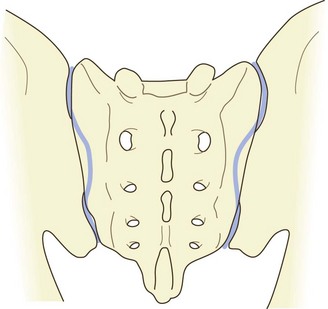

The first design imperative is to lock the sacrum into the pelvis. To this end, the articular surface of the sacrum presents an irregular contour, marked by ridges, prominences, troughs and depressions (Fig. 14.1). These are matched by reciprocal depressions, troughs, prominences and ridges on the ilium, so that the bones can lock into one another. This gives the sacroiliac joint a sinuous appearance in frontal view (Fig. 14.2).9

Figure 14.2 A posterior view of the sacroiliac joints showing the sinuous shape of the joint cavities.

Particularly evident is a major depression on the sacral surface, on the S2 segment, which receives a major prominence from the ilium, the latter being known as Bonnaire’s tubercle.10

A further feature, noted in textbooks of anatomy11 but not verified by modern quantitative studies, pertains to the plane of the joint. The articular surface of the sacrum is twisted from above downwards. Opposite the S1 segment, the dorsal edge of the articular surface projects slightly further laterally than the ventral edge. Conversely, at the S3 segment, the ventral edge projects slightly more laterally than the dorsal edge. Because of this, when viewed in transverse section, the sacrum is wedge shaped but in opposite directions at opposite ends of the sacroiliac joint. At the S1 segment, the posterior width of the sacrum is greater than its anterior width. Conversely, at the S3 segment, the anterior width is greater than its posterior width (Fig. 14.3).

Cartilage

The cartilages differ on the sacrum and ilium. The sacral articular cartilage is normally white and smooth, and has the features of typical hyaline cartilage.12 Its thickness ranges from 1 to 3 mm.13 The iliac cartilage is duller in appearance and is marked by dense bundles of collagen, which give it the appearance of fibrocartilage,12 but histologically and biochemically it is nonetheless hyaline in nature.14 It is usually less than 1 mm thick. Its cell density, however, is greater than that of the sacral cartilage.15 Meanwhile, the subchondral plate of the ilium is some 50% thicker than that of the sacrum.15

The reasons for these differences between the sacral and iliac cartilages has not been established. One contention, however, is that the sacral cartilage is designed for transmitting forces (from the spine to the pelvis) whereas the iliac cartilage is designed to absorb them.15

Articulation

When articulated between the two ilia, the sacrum is held firmly in place by bony locking mechanisms. The interlocking contours of the sacrum and ilium prevent downward gliding of the sacrum under body weight. Indeed, the friction coefficient of the sacroiliac joint is larger than that of the knee and is considerably greater in proportion to the prominence of the ridges and depressions of the articular surface.16