Students who successfully complete this chapter will be able to do the following: • Name the three types of memory and describe how each is used. • Name the three types of learning and describe how each is used. • Discuss the recommended methods of taking notes while reading or listening to tapes or lectures. • Discuss the competencies commonly evaluated in clinical education. • Discuss the various types of educational and training options available to sonographers. Educating sonographers should be no different. Old habits die hard, however, and some students begin their sonography education expecting to be handed a master list of facts to memorize. Such students are doomed to frustration until they realize that working in the field of diagnostic medicine is a problem-solving activity, comparable to working on a complex jigsaw puzzle. Simply taking an inventory of all the puzzle pieces does not provide the answers. The key to a solution lies in observing how the shapes of individual pieces may interconnect with other pieces in various areas of the puzzle. Only through trial and error and by blending experience (memory) and logic (reasoning) can difficult puzzles be solved correctly. (The topic of critical thinking is discussed in further detail in Chapter 3.) Students who want to learn must increase their reading rate and listening skills. People rarely listen with maximum efficiency, and they consciously pay attention to only a fraction of what they hear. The average speaking rate has been measured at approximately 125 words per minute, whereas the average listening and thinking rate is 400 words per minute.1 Such a large time lag encourages the mind to wander. Successful students must develop methods to increase their attention span by becoming effective listeners. Hearing and listening are not the same thing; listening is a cognitive act that requires you to pay attention and mentally process what you hear. Immediate memory is extremely limited. People can respond to only one thing at a time, and information retention is limited to only two to four items.2 Another problem with immediate memory is that it requires singular attention to determine which items require prompt response and which items require transfer from the immediate memory before they decay and are lost forever. Long-term memory is used for information that must be stored for long periods (days, months, years) before use. Retrieving information from the long-term memory collection requires a search. If the long-term memory is unorganized, a big load is placed on the short-term memory. For this reason, processing incoming information correctly is important; otherwise, it will be irretrievable. The major advantages of the long-term memory system are (1) its limitless capacity to store information and (2) the number of items it can retain. Long-term memory facilitates learning and the memorization of new material. It is believed that the more information stored in long-term memory, the easier it is to enter new information.3 Storing information in long-term memory requires attention, organization, and association (Figure 2-1). Attention is focusing on desired material and blocking out any disturbing stimuli. The primary purpose of attention is to determine what is important enough to remember. Organization is the art of putting memory in order. The human mind is like an expanding library ofall previously acquired knowledge, stored by appropriate categories. Every time new knowledge is acquired, it is added to any associated facts that were stored previously, always available to be checked out. If a particular category of facts is used or added to only infrequently, it is treated as inactive and displaced to make room for new or additional facts. This process is unfortunate because inactive information sometimes is difficult to locate or may even become lost. Although complete elimination of inaccurate remembering is impossible, certain strategies can facilitate an accurate memory. The key lies in remembering well and correctly. Students can take notes to ensure the information they want to recall is remembered accurately. Understanding a subject clearly from the start makes errors in thinking much less likely. It has been proven that memories improve also if the body is prepared for the task.4 Rest, sufficient sleep, and healthy eating habits (particularly eating breakfast) improve the brain’s ability to function. Visual or verbal associations bridge memory gaps and enhance remembering. Figure 2-2 shows some examples of association. The most successful associations are tied to prior knowledge. For instance, someone may choose to remember the number of white and black keys on a piano (52 white keys and 36 black keys) by associating them with the 52 weeks in a year and 36 inches in a yard. Sometimes, the similarities in spelling two different words can cause memory difficulties. For example, with the words stationery and stationary, it may be helpful to remember that the “e” in stationery stands for letters, whereas the “a” relates to movement. The use of acronyms, initials, and acrostics can make material meaningful by gathering information into mnemonic clusters to reduce the amount of information to remember. For example, the names of the Great Lakes form the acronym HOMES, which stands for Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior. Acronyms and initials are used widely to represent associations, organizations, government agencies, and military titles and terms (Box 2-1). The obvious value of memory aids is that they make people organize, associate, and visualize meaningful information, forcing them to concentrate and pay attention. The painful truth is that the things people understand do not require memorization; people only memorize the things they do not understand. Box 2-2 suggests steps to enhance your memory. • Problem solving: Students construct knowledge as they recognize problems, formulate solutions, and arrive at conclusions. • Communication: Learning to express ideas and understand the ideas of others requires communication. • Collaboration: Learning is a social process that requires students to value and work with others. • Connections: Knowledge does not exist in isolation. Students must learn that all of the content areas of ultrasound are connected. They must understand and practice this skill to form a comprehensive understanding of the physical principles and scientific aspects of diagnostic ultrasound. All students take in and process information in different ways, so it is important to determine what your learning style is based on how you learn best. No matter what learning styles other students have, your learning style is your strength. The three most frequently identified learning styles are visual learning, auditory learning, and active, or tactile, learning.5,6

The Sonographer as Student

Learning dynamics

Critical Thinking and Action

Effective Listening

Memory

Immediate Memory

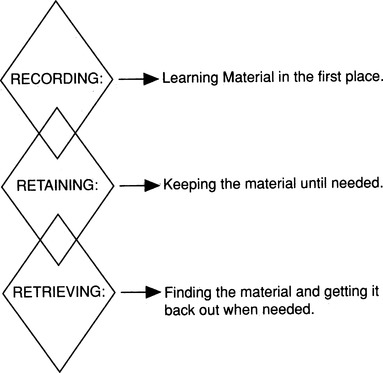

Long-Term Memory

Inaccurate Memory

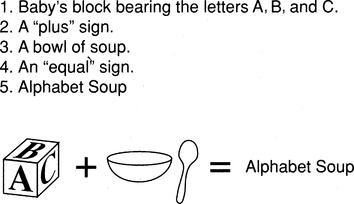

Memory Techniques

Learning styles

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine