Key Points

- ▪

The chest radiograph is useful to prompt consideration of aortic pathologies but is not able to reliably offer a final diagnosis for most, which is reserved for more advanced imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and aortography.

- ▪

The silhouettes of the aorta should be understood in detail, as should the imaging features on radiography, and by other modalities, of specific acquired, congenital, and repaired aortic pathologies.

Issues Concerning Chest Radiographic Imaging of the Thoracic Aorta

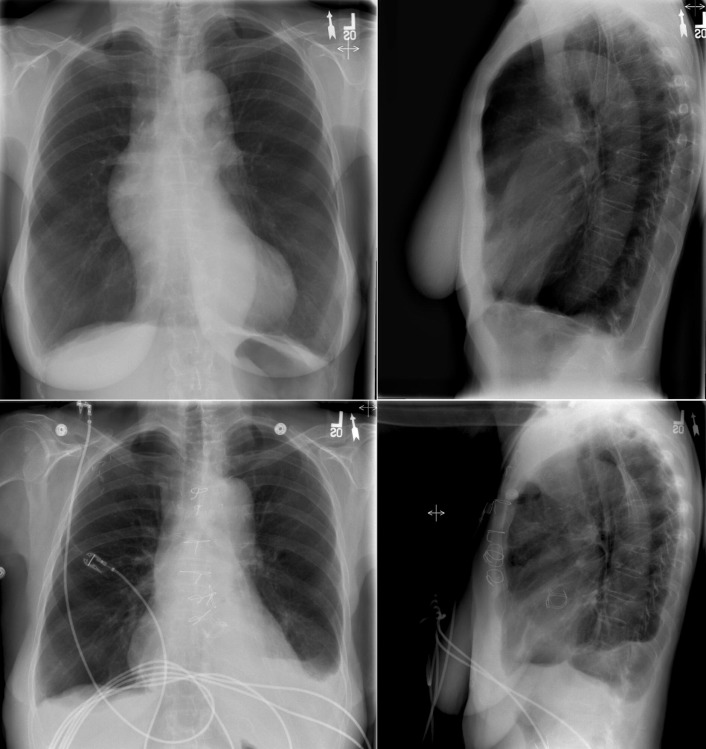

It is important to remember that (1) the chest radiograph does not image the aorta comprehensively and (2) abnormalities of the aorta evident on the chest radiograph represent substantial pathology that is often clinically important and sometimes life-threatening. Therefore, to not overlook major aortic pathology when reading a chest radiograph, it is imperative to scrutinize aortic contours and appearance ( Fig. 7-1 ). The aorta is evident on the chest radiograph wherever the air-filled lung is in contact with it and there is a silhouette to evaluate.

It is critical to recall that major aortic pathologies, such as dissection, may occur with a normal or near-normal chest radiograph. A final diagnosis for aortic pathology requires a more advanced and comprehensive test such as CT, MRI, TEE, or aortography.

Review of Silhouettes of the Aorta

The aortic root begins behind the pulmonary artery at the level of the aortic valve and lies within the pericardium. The root is surrounded by soft tissue (the pulmonary artery in front, the left atrium inferiorly, the pericardium, and pericardial and mediastinal fat) and the aortic valve is usually not evident unless it is either heavily calcified or prosthetic; therefore, the aortic root cannot be localized accurately on the chest radiograph on either the frontal or lateral radiographs. Marked dilation ( Graphic 7-1 ) of the root, which usually occurs concurrently with dilation of at least the ascending aorta, is evident on the chest radiograph. The ascending aorta, the continuation of the aorta after the root, is better depicted on the lateral chest radiograph, and when enlarged, the ascending aorta may also be seen on the frontal chest radiograph. The aortic arch is fairly well depicted on the lateral radiograph, but the images are foreshortened and the orientation of the arch in the chest renders considerable variability in its appearance. The superior and lateral aspects of the distal portion of the arch are generally well depicted on the frontal radiograph in the region egregiously referred to as the “knuckle.” The lateral aspect of the proximal descending thoracic aorta is again well depicted as it abuts (normally) air-filled lung, but the medial portion lies against the thoracic vertebrae; therefore, the medial border of the proximal descending aorta is very difficult to identify on the chest radiograph. The middle and lower portions of the thoracic aorta, which run downward with the lateral portion abutted by lung, are well visualized. The medial portion, which lies generally against the vertebral column, is poorly seen. The middle and lower portions of the thoracic aorta are frequently rendered tortuous by disease, especially aneurysmal and hypertensive disease. The cardiopericardial silhouette (CPS) may obscure the middle and lower thoracic aorta on the frontal radiograph.

Acquired Pathologies of the Aorta

Atherosclerosis

Advanced atherosclerosis of the aorta is radiographically evident as associated intimal calcification ( Fig. 7-2 ). Aortic calcification is usually caused by atherosclerosis, although syphilitic and noninfectious aortitis may result in calcification. Calcification due to atherosclerosis is best appreciated on the frontal chest radiograph and is seen in the distal aortic arch/proximal descending aorta. Perhaps the most commonly calcified site of the thoracic aorta is the floor and lateral wall of the distal arch, which happens to project edge-on and quite cleanly and clearly on the frontal projection.

Calcification due to atherosclerosis resides in intimal plaques and therefore serves as a marker of the inner surface of the aorta such that aortic wall thickness can be estimated when the diagnosis of aortic dissection is sought. Aortic intimal calcification is most visible on the lateral wall of the aortic “knuckle.” Calcification of the ascending aorta is most commonly due to atherosclerosis but may also be caused by syphilis or aortic vasculitis. Gross calcification of the ascending aorta visible on the chest radiograph is worrisome to the cardiovascular surgeon because it engenders difficulty in cross-clamping the aorta and increased stroke risk with bypass. Other consequences of atherosclerosis that may be evident on the chest radiograph are elongation and tortuosity of the aorta, which result in greater prominence of the aorta and a higher aorta in the chest ( Fig. 7-3 ).

Arterial Hypertension

Long-standing hypertension results in elongation, tortuosity, and atherosclerosis of the aorta, as well as occasionally mild dilation, dissection, or aneurysmal formation of the aorta. As with atherosclerosis, the aorta is more evident in patients with hypertension because of its unfolding.

Aneurysms and False Aneurysms of the Aorta

Aneurysmal disease of the aorta may occur without antecedent disease (hypertension, aortitis, or associated aortic valvulopathy), particularly when the aortic syndrome is heritable/familial. Most aneurysms of the thoracic aorta are apparent on the PA chest radiograph, although aneurysms at the root and ascending level, and also ones posterior to the heart, may be difficult to appreciate with any confidence ( Figs. 7-4 to 7-9 ) unless they are very large ( Fig. 7-10 ). The impossibility of having both sides of the aorta silhouetted against air makes it impossible to establish maximal transverse diameter of an aneurysm accurately, except for a few arch-only aneurysms. Furthermore, there are insufficient signs available in the chest radiograph to ascertain the development of a dissection of an aneurysm. The lateral radiograph contributes to the perception of thoracic aneurysms, and as well, the lateral chest radiograph may inadvertently capture the finding of a calcified anterior wall of an abdominal aortic aneurysm—if the field of view and penetration are optimal. (See Figures 7-11 to 7-24 ; see also Graphic 7-1 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree