17

Thoracic Outlet and Upper Extremities

Indications for Arteriography and Venography of the Thoracic Outlet and Upper Extremities

Indications for Arteriography and Venography of the Thoracic Outlet and Upper Extremities

Indications for arteriography of the thoracic outlet and upper extremities include the evaluation of upper extremity ischemia, trauma, aneurysms, vasculitides, and arteriovenous malformations. Venography of the thoracic outlet and upper extremities are used routinely in the evaluation of thoracic outlet obstruction, superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, and hemodialysis access shunts.

Techniques of upper-extremity arteriography

Vascular access for upper-extremity arteriography can be achieved by using a 4 or 5 Fr diagnostic catheter using the Seldinger technique via a transfemoral approach. Additionally, access can be achieved either from an axillary or from a brachial artery approach if the transfemoral approach is not technically feasible. The axillary approach has fallen out of favor because of the potential for brachial plexus injury caused by an access site hematoma. The reported frequency of brachial plexus injury has been between 0.4 and 9.5%. The axillary approach has been replaced by the brachial artery approach.1 A Headhunter-type catheter may be used to catheterize the brachiocephalic vessels in younger patients, but catheterization may be accomplished more easily by using a Simmons-type catheter in older patients who have tortuous vessels.

The examination should begin with thoracic arch aortography. A complete arteriographic examination of the upper extremities necessitates evaluation of the entire vasculature from the origins of the brachiocephalic and left subclavian arteries to the level of the digital arteries. It is imperative that the arteries of the entire extremity be evaluated thoroughly because abnormalities of the inflow arteries may result in distal clinical symptoms. Furthermore, as many as 15% of patients have an aberrantly high origin of the radial artery arising from the axillary artery, a finding that may be overlooked if evaluation of the more proximal vessels is neglected (Fig. 17-1). Less frequently, the ulnar artery has an aberrantly high origin arising from the brachial artery.2

Arterial spasm may be encountered during arteriography of the upper extremity but usually subsides spontaneously or after the intraarterial injection of medications such as tolazoline, phentolamine, or nitroglycerin. These vasodilators also enhance blood flow to the distal extremity, improving digital artery visualization.3 The temperature of the upper extremity is a critical factor influencing vascular tone and blood flow to the hand and digits. Decreased skin temperature may result in spastic narrowing of blood vessels, whereas temperature elevation improves blood flow. It is well known that artificial temperature elevation with the use of heating pads or warm water improves visualization of distal arteries of the upper extremity and hand.4 Older techniques of promoting vasodilatation, such as general anesthesia, stellate ganglion blockade, and oral alcohol, have fallen into disuse.5

Attention must be given to secondary signs that indicate the presence of vascular disease such as opacification of collateral vessels or retrograde filling of the vertebral artery as a result of a proximal subclavian artery or brachiocephalic artery stenosis. These secondary findings are important because less complete views of the upper extremities may fail to uncover significant underlying disease.

FIGURE 17-1. High origin of the left radial artery (arrow) from the brachial artery.

Upper-extremity arterial contrast injections can be quite painful; however, the degree of discomfort has been decreased since the introduction of digital subtraction angiography (DSA), which allows for the use of more dilute and lower volumes of contrast media compared with cut-film angiography. Newer, low-osmolar contrast agents tend to be better tolerated than the standard high-osmolar agents.6

Disease entities

Conditions resulting in upper-extremity arterial insufficiency may be attributable to abnormalities extending from the inominate or subclavian arteries to the digital arteries. The etiologies of critical ischemia of the upper extremity are quite variable, involving both small- and large-vessel arteridites, trauma, atherosclerosis, and vascular complications secondary to thoracic outlet obstruction.7

Atherosclerosis

Manifestations of atherosclerosis of the upper extremities vary widely and usually involve proximal rather than distal arteries.1 Symptoms include claudication, ulcers, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. The left upper extremity is more commonly the symptomatic extremity. This is attributed to the perpendicular origin of the left subclavian artery from the aortic arch.8

In upper-extremity claudication, multiple segmental occlusions may be identified (Fig. 17-2). Less frequently, embolization may occur, resulting in distal ischemia of the upper extremity.9 Most emboli arise from a cardiac source, such as emboli resulting from atrial fibrillation or endocarditis.3,10–12 Emboli may be secondary to atherosclerosis, frequently within the subclavian artery, or as the result of arterial injury secondary to trauma (Fig. 17-3). In up to one third of cases, digital ischemia may be due to embolic occlusion and may mimic primary distal disease of the upper extremities. Therefore, evaluation of the proximal vessels during angiography is imperative.3

The goal of arteriography in the setting of embolic occlusion is to demonstrate arterial reconstitution distal to the site of occlusion so that proper management may be planned, such as surgical embolectomy, surgical bypass, or transcatheter thrombolysis. Catheter-directed thrombolysis is frequently the initial treatment of choice.13

Trauma

Indications for arteriography for the evaluation of trauma include diminished or absent distal pulses, the presence of a bruit, pulsatile or expanding hematoma, hemothorax, electrical trauma. Trauma to the vessels of the thoracic outlet and upper extremities is classified by the mechanism of injury as penetrating or nonpenetrating. Both types of injuries are potentially limb threatening.

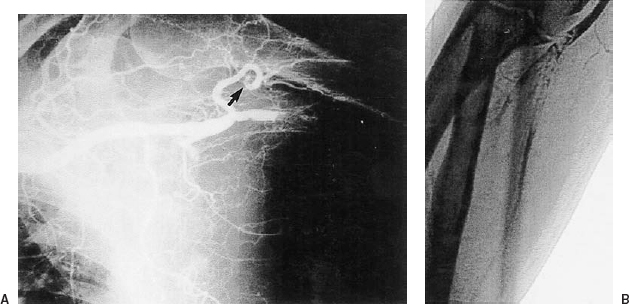

Penetrating trauma from either gunshot or knife wounds is frequently encountered in the emergency setting. Penetrating trauma may lead to direct intimal injury, vessel transection with or without extravasation of blood and formation of pseudoaneurysms (Fig. 17-4), dissection, occlusion, spasm, arteriovenous fistula formation (Fig. 17-5), and arterial displacement by hematoma. Slow antegrade flow of blood may be identified angiographically and is often due to spasm induced by the trauma itself or to compartment syndrome.14

FIGURE 17-2. Atherosclerosis in long-standing diabetes; extensive stenotic and occlusive disease of the medium and small vessels of the forearm and wrist.

FIGURE 17-3. A: High brachial artery embolic occlusion in a patient with atrial fibrillation and acute onset of ischemic left upper extremity pain. Note the smaller filling defect in the humeral circumflex branch (arrow). B: Distal emboli in the proximal right radial and ulnar arteries evident by “tram track” filling defects. Patency was reestablished after transcatheter thrombolysis.

Repetitive blunt trauma may result in pathologic changes in the vessel, including intimal tears or pseudoaneurysms with mural thrombus formation. In turn, this thrombus may result in distal embolization and consequent ischemia. Therefore, prompt diagnosis is critical to minimize morbidity.15 This type of injury is seen in athletes in whom repetitive motion is the underlying cause of injury. These patients may develop signs and symptoms of acute ischemia of the hand and digits. Some may progress to tissue breakdown evident by skin ulceration and gangrene.8 The angiographic appearance may be similar to that seen in atherosclerosis with multiple segmental arterial occlusions.12

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Raynaud’s phenomenon is an idiopathic vasospastic condition of the small vessels of the extremities characterized by episodic digital ischemia provoked by cold, emotion, and other sympathetic stimuli.16 Patients with this condition, most frequently women, develop trophic changes as a result of microcirculatory damage and prolonged local ischemia.17 It is more often symptomatic in the upper extremities than in the lower.1 Raynaud-type symptoms are common in the general population, and in a minority of these patients, it may be attributable to an underlying, often reversible cause (primary Raynaud’s phenomenon or Raynaud’s disease), or it may be attributable to a known underlying systemic illness (secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon) such as systemic lupus erythematosis, scleroderma, or rheumatoid arthritis. Other associated conditions include drug or chemical injury, occupational injury, occlusive arterial disease, and hyperviscosity diseases.16,18

FIGURE 17-4. Stab wound to the axilla with transection and pseudoaneurysm of the proximal right brachial artery but with continued distal flow.

FIGURE 17-5. Traumatic arteriovenous fistula involving the right sublavian artery and brachiocephalic vein following a gunshot wound. Note the bullet fragments.

Symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon include pain, paresthesias, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor. Small digital ulceration and or fissuring over the pads of the digits can be seen in severe or recurrent attacks. Gangrene only rarely occurs.17,18

Primary Raynaud’s phenomenon typically presents during the teenaged years in women who are otherwise healthy, but symptoms may develop as late as the fourth decade. It has been suggested that persons with this condition have a higher incidence of other vascular complications, such as migraine headache, hypertension, and atypical angina.18

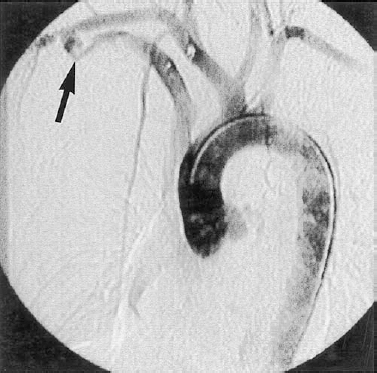

Although angiography is not particularly useful in the diagnosis or distinction of the various causes of Raynaud’s phenomenon, it does, however, have a role in the evaluation of patients presenting with unilateral symptoms. Patients with unilateral symptoms frequently have identifiable underlying upper-extremity pathology of either the major or smaller vessels. An arteriographic finding is stenosis of the subclavian artery. This is usually a result of an extraluminal abnormality. Stenosis can lead to poststenotic aneurysmal dilatation, which may in turn lead to the development of mural thrombus and subsequent embolization with distal ischemic changes.19

The typical angiographic findings of Raynaud’s phenomenon are those of spasm with slow antegrade flow (Fig. 17-6) and poor opacification of the distal small vessels. Angiography following the injection of vasodilators can lead to dramatic improvements in visualization of small distal arteries.1

Vasculitides

All the several categories of vasculitides are relatively rare and affect the upper extremities. These conditions may affect the arteries primarily or relate to a systemic disease process; however, they all share the characteristic of arterial wall inflammation and often necrosis. Differentiation of these vasculitides is best accomplished by a thorough review of the clinical history, with particular attention to the distribution of vessel involvement as well as the rapidity of onset. The pathogenesis and etiologies of these vasculitides are poorly understood, but most investigators agree that a relationship to immune complex and cell-mediated mechanisms exists.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree