, Stefano Fanti1 and Lucia Zanoni1

(1)

Department of Nuclear Medicine, Universitary Hospital Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF)

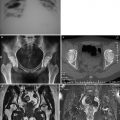

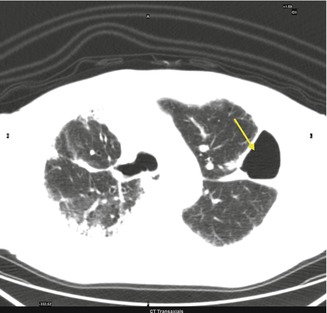

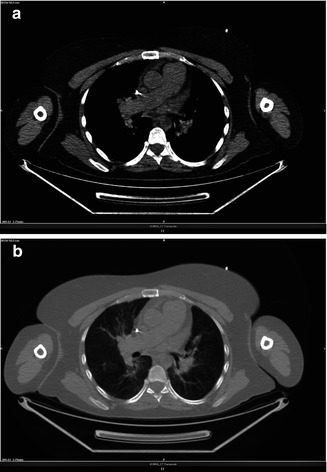

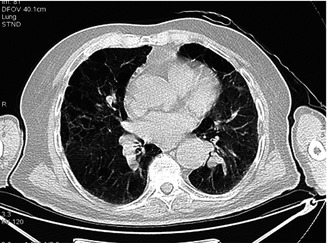

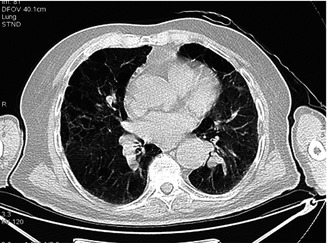

Fig. 3.1

(a–d) Interstitial distortion in both lungs, most evident in the lingula and less evident in lower dorsal lobes

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic progressive pulmonary disease of unknown etiology. It is primarily diagnosed on the basis of clinical, physiologic, and radiologic criteria. In its International Consensus statement, the American Thoracic Society defines IPF as a specific chronic interstitial pneumonia that is limited to the lung and that has the histological appearance of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) on open or thoracoscopic biopsy.

CT manifestations of IPF consist of symmetric bilateral reticulation, architectural distortion, and honeycombing involving mainly the subpleural lung regions and lower lobes. The active stage of the disease, which is characterized by active alveolitis and hazy ground-glass opacifications, is potentially reversible and potentially amenable to treatment, unlike end-stage disease, characterized by honeycombing without ground-glass attenuation in typical distribution, which is irreversible. In 50 % of cases the CT findings may mimic those of other interstitial lung diseases being relatively nonspecific.

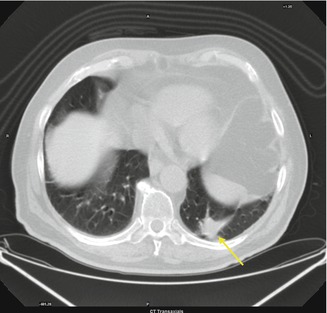

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP)

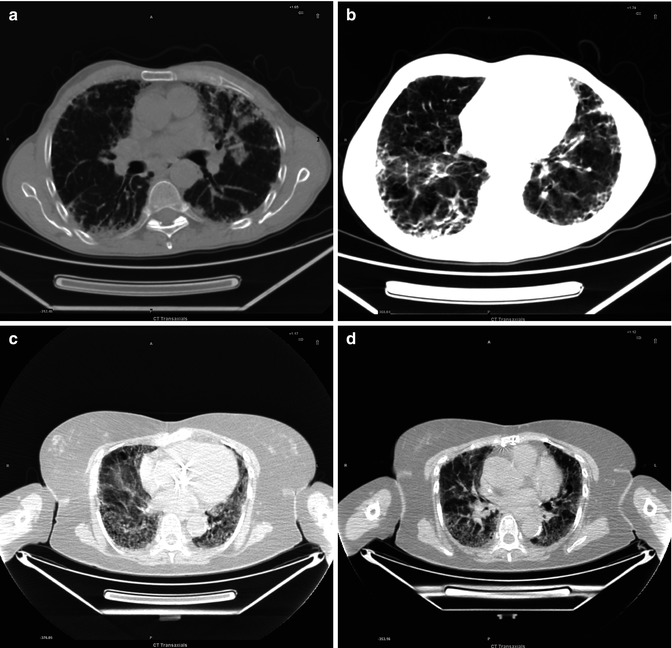

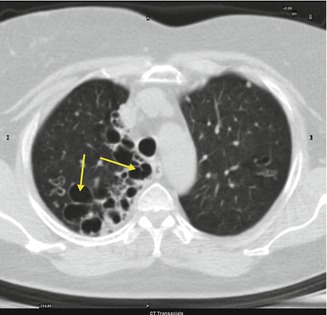

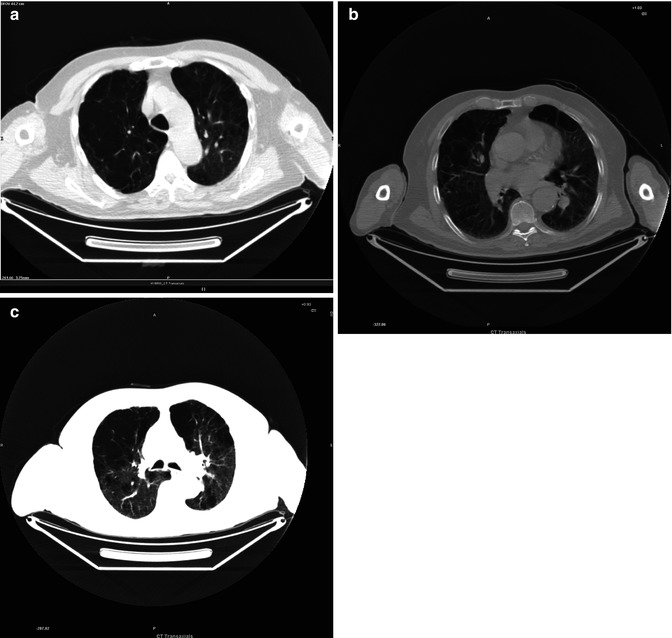

Fig. 3.2

(a–c) Basal (a), middle pulmonary (b) and apical periferal architectural distorsion resulting from fibrosis and producing traction bronchiectasis (arrows)

It is one of the most common interstitial lung diseases. It shows typically an apicobasal gradient with predominantly basal and peripheral reticular pattern with honeycombing and traction bronchiectases (a very good differentiating feature from patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and concurrent emphysema). Architectural distortion, meaning lung fibrosis, is often prominent. In cases of more advanced fibrosis, lobar volume loss is seen. Cross-sectional imaging also reveals heterogeneous, with areas of fibrosis alternating with areas of normal lung, indeed it is often patchy. The term idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is now applied solely to the clinical syndrome associated with the morphologic pattern of UIP.

Right Superior Lobectomy Scarring

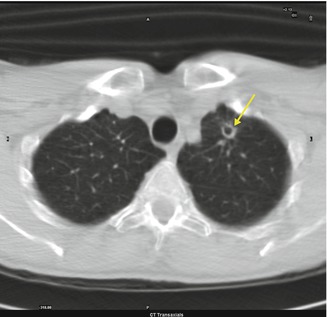

Fig. 3.3

Fibrotic area in the right apical lung connected to the pleura (arrow)

Pulmonary scarring usually occurs after surgery. At CT there are fibrotic areas connected to the pleura and an expansion of the residual lung parenchyma. Surgical clips may appear as small hyperdense dots.

Pneumothorax

Fig. 3.4

Abnormal collection of air or gas in the pleural space that separates the lung from the chest wall

Abnormal collection of air or gas in the pleural space that separates the lung from the chest wall. Complication of medical or surgical intervention. CT shows even the smallest pneumothorax. Air density (blackness) is the same inside and outside the chest. A compressed lung segment can be also noted.

Bronchiectasis

Fig. 3.5

Right pulmonary bronchiectasis (arrows)

Dilated airways (tram lines) with a signet ring appearance with a luminal diameter >1.5 times that of the adjacent vessel in cross section or by grapelike clusters in case of mire severity. Other findings can be thickening of the bronchial walls due to peribronchial fibrosis, obstruction of airways (opacification and air trapping), and consolidation.

On the contrary bulla generally has no definable wall thickness and no accompanying vessels.

Mycotic Lung Infection

Fig. 3.6

Left pulmonary nodular cavitated lesion (arrow)

Fungal infection occurs following the inhalation of spores, after the inhalation of conidia, or by the reactivation of a latent infection. When the process is recovering, a nodular lesion usually surrounded by a ground-glass opacity or halo, and cavitated, can be found. Air crescent sign can be detected in which crescentic air space separates the cavity from the fungus ball.

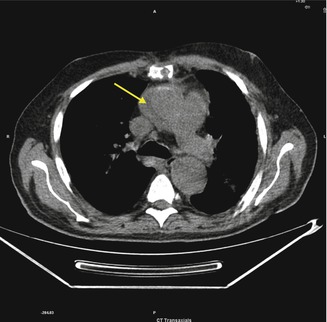

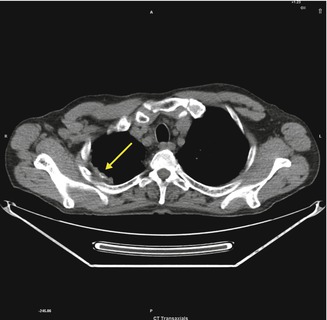

Para-Aortic Arch Abscess

Fig. 3.7

A low-attenuation fluid collection adjacent to the ascending aorta (arrow)

Postsurgical Lung Changes

Lung changes occur after surgery. Fibrotic areas generally connected to the pleura and surgical clips may appear at CT images.

Fig. 3.8

Patient affected by secondary lung lesion from colon cancer underwent left inferior lobe nodulectomy

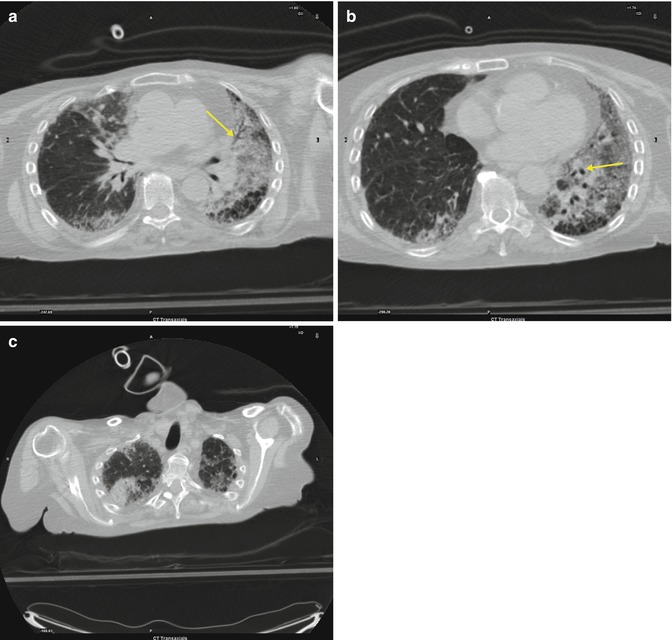

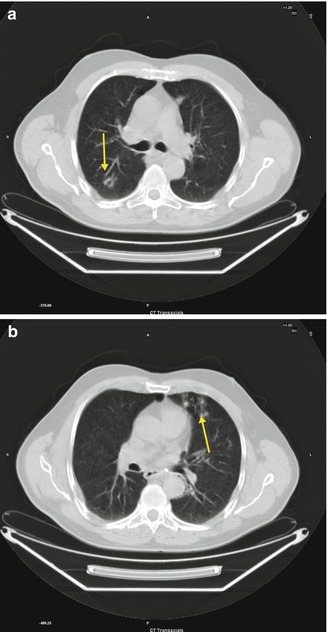

Peribronchial Inflammation

Fig. 3.9

Bronchiolar dilatation (a, arrow), and bronchiolar luminal impaction (b, arrow)

Direct CT signs of bronchiolar disease include bronchiolar wall thickening, bronchiolar dilatation, and bronchiolar luminal impaction. Indirect signs include subsegmental atelectasis and air trapping.

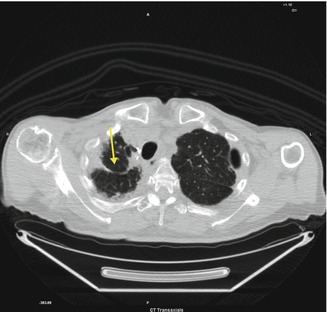

Asbestosis Pleural Plaques

Fig. 3.10

Right apical and calcified pleural plaque caused by asbestos exposure (arrow)

Circumscribed pleural plaques are the most common manifestation of asbestos exposure and comprise discrete areas of white or yellow thickening on the parietal pleura. They are frequently bilateral and symmetric and occur particularly on the posterolateral chest wall between the fifth and eighth ribs, over the mediastinal pleura, and on the dome of the diaphragm. Histological examination reveals plaques to be acellular, with a “basket-weave” pattern of hyalinized collagen strands. They are covered by a single layer of normal mesothelial cells on the pleural surface.

Pleural plaques typically develop 20–30 years after exposure, and their incidence increases with longer duration of exposure. They are found in as many as 50 % of asbestos-exposed workers, but may also occur after low-dose exposures. The total surface area of pleural plaques measured via CT does not appear to be related to cumulative asbestos exposure.

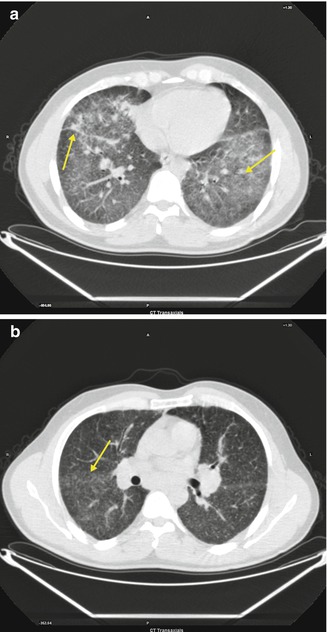

Pulmonary Sarcoidosis

Fig. 3.11

(a, b) Multiple small nodules in a peribronchovascular distribution along with irregular thickening of the interstitium (a, b, arrows)

Systemic disorder of unknown cause that is characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas and the proliferation of epithelioid cells. Pulmonary infiltrates are typically represented by nodules, interstitial thickening, and fibrosis. Multiple small nodules in a peribronchovascular distribution along with irregular thickening of the interstitium are typical CT findings of sarcoidosis.

Klebsiella Pneumonia

Fig. 3.12

History of right superior lobectomy for adenocarcinoma without radiation treatment (FDG avid)

Klebsiella pneumonia is a form of bacterial pneumonia associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae. Common CT findings in patients with acute Klebsiella pneumonia are ground-glass attenuation, consolidation, and intralobular reticular opacity. They can be mainly found in the lung periphery and in both sides of the lungs. Often they are associated with pleural effusion (>50 %).

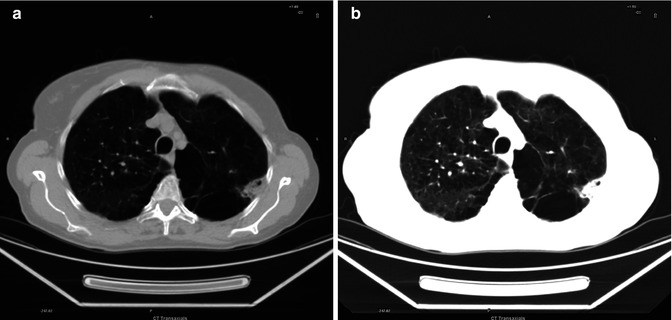

Pulmonary Hypertension

Fig. 3.13

(a, b) Central pulmonary artery dilatation

Pulmonary arterial hypertension may be idiopathic or arise in association with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism (caused by tumor cells, parasitic material, or foreign material), parenchymal lung disease, liver disease, vasculitis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or a left-to-right cardiac shunt. Features of pulmonary arterial hypertension that may be seen at CT are markedly enlarged pulmonary arteries with tiny branching smaller vessels, abrupt narrowing or tapering of peripheral pulmonary vessels, right ventricular hypertrophy, enlarged chambers of the right heart, dilated bronchial arteries, and a mosaic pattern of attenuation due to variable lung perfusion.

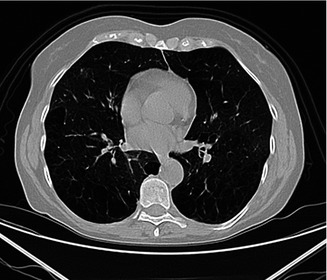

Paraseptal Emphysema

Fig. 3.14

(a–c) Mosaic patterns of attenuation due to variable lung perfusion

Fig. 3.15

(a, b) Mosaic pattern of attenuation (a intermediate mediastinal-lung window; b lung window)

Fig. 3.16

Small air-density areas mainly concentrated adjacent to the pleural surfaces

Paraseptal emphysema affects the peripheral parts of the secondary pulmonary lobule and is usually located adjacent to the pleural surfaces and pleural fissures. The affected lobules are almost always subpleural and demonstrate small focal air-density areas up to 10 mm in size. The emphysematous spaces are not bounded by any visible wall. It is also associated with smoking and can lead to the formation of focal air-density areas larger than 10 mm called as subpleural bullae or blebs and spontaneous pneumothorax.

Fig. 3.17

Another pattern of emphysematous spaces in both lungs

Centrilobular Emphysema

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree