Thorax: The Lungs

Diffuse Lung Disease

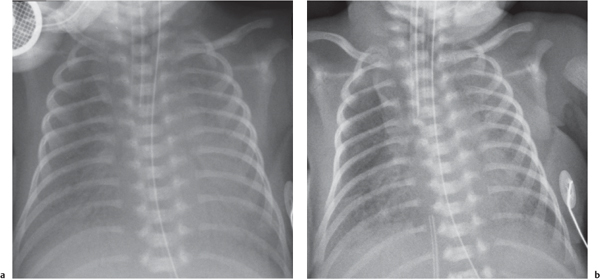

Lung Disease in the Neonate

The differential diagnosis for diffuse lung disease in the neonatal period is relatively narrow. The final diagnosis is reached by a combination of clinical and radiologic findings. Knowing the gestational age of the neonate is essential to constructing a sensible list of possibilities.

Diffuse Lung Disease Beyond the Neonatal Period

Characterizing diffuse lung disease requires a determination of the characteristics of the opacification, as discussed subsequently.

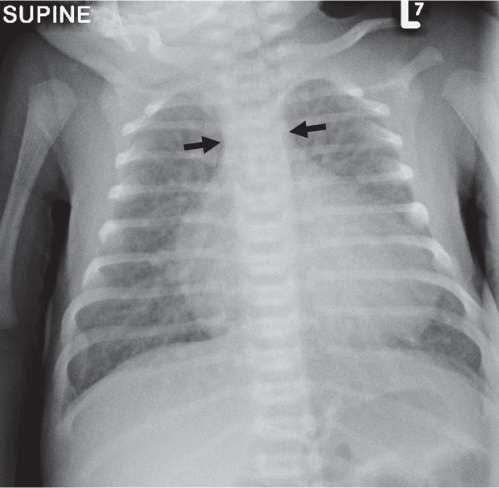

Bilateral Homogeneous Opacification: Bilateral Lung “White Out”

Increased vascular opacities

Diffuse airspace opacification

Diffuse peribronchial opacification

Reticulonodular opacification

Cystic lung disease

Nodular opacification: miliary pattern

Generalized patchy opacification

Diffuse hypertransradiancy/lung overinflation

Clearly, there is overlap between these groups.

Increased Vascular Opacities

Distinction between pulmonary venous and arterial dilatation is not always straightforward, and the two may coexist. In venous dilatation, the enlarged vessels are less well defined than in arterial dilatation and have a vertical course in the upper zones with a horizontal course in the lower zones. In pulmonary arterial dilatation (pulmonary plethora), dilated arteries radiate from the hilum: the central pulmonary arteries and pulmonary outflow tract may also be dilated.

Diffuse Airspace Opacification

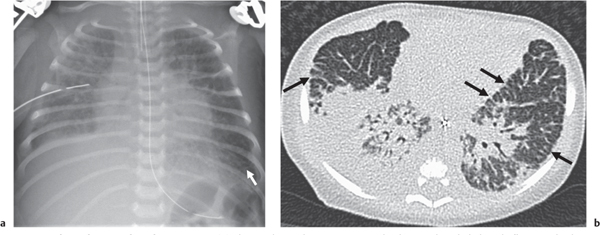

Diffuse Peribronchial Opacification

Peribronchial opacification is a common finding in pediatric chest radiology, particularly in younger children. There appears to be a greater propensity for respiratory infections to involve small- and medium-sized airways in younger children. Smaller airway luminal size means peribronchial thickening often results in airway obstruction, usually manifest as air trapping.

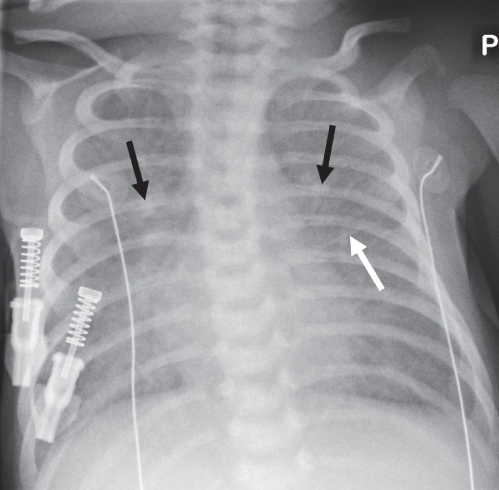

Reticulonodular Opacification

A reticulonodular pattern (i.e., one consisting of discrete nodular and linear opacities) is typically due to disease of the pulmonary interstitium. The exact pattern depends on the distribution of changes. Thickening of the peribronchovascular interstitium results in peribronchial thickening centrally, but peripherally results in branching nodular opacities. Thickening of the interlobular septa results in septal lines: these may appear as vertically oriented lines in the upper zones, horizontally oriented lines in the lung periphery, or diffuse spidery lines throughout the lungs. Lung reticulation on a radiograph may also result from cystic change due to overlapping cyst walls, as in diffuse cystic lung diseases, from end-stage fibrotic changes (“honeycombing”), and from overlapping bronchial walls in severe bronchiectasis.

Cystic Lung Disease

This category covers the radiographic appearance of diffuse rounded lucencies in the lungs: these may represent cysts or features that merely simulate a cystic appearance (“pseudocystic”; see also the section on focal lung lucencies).

Nodular Opacification: Miliary Pattern

A miliary pattern refers to diffuse small nodules that are 1 to 2 mm in size, named as such because they resemble millet seeds.

Generalized Patchy Opacification

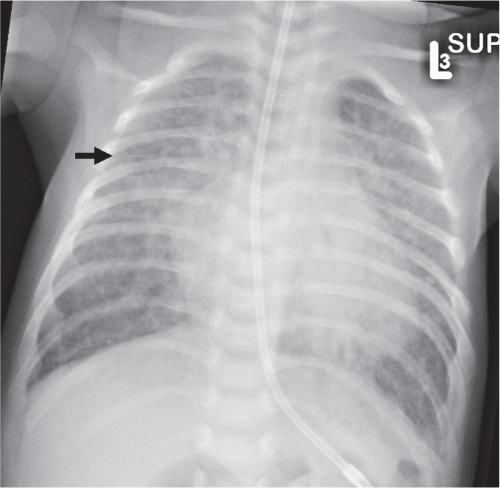

Diffuse Hypertransradiancy

This is a relatively common pattern in children and generally implies diffuse air trapping due to valvelike obstruction of medium and small airways.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree