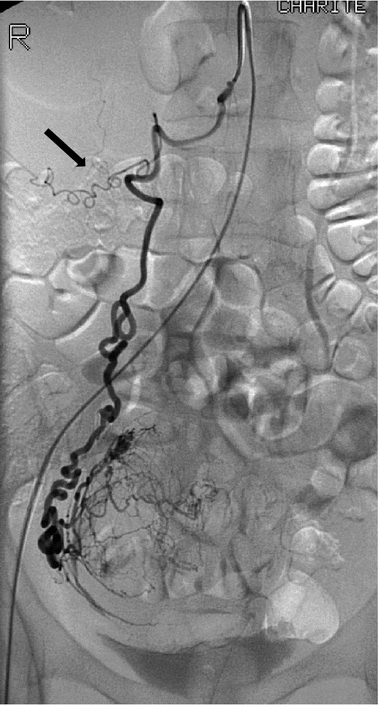

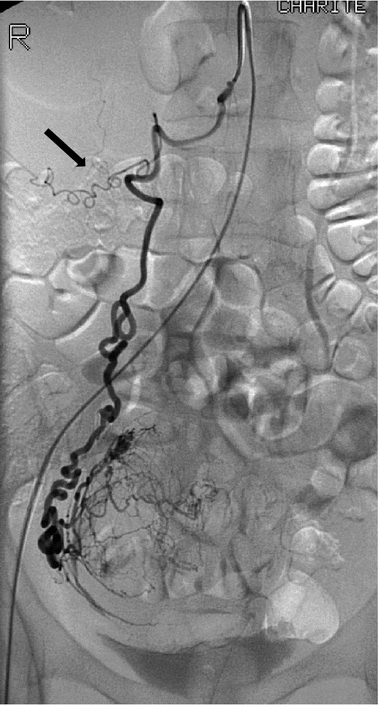

Fig. 1

Flush aortography with a pigtail catheter positioned at the level of the renal arteries shows enlarged ovarian arteries (black arrows) which descend retroperitoneally into the pelvis and show the typical corkscrew appearance distally

They may also arise above or below the renal pedicle from L1 to L4. In cadaveric studies, it is reported that in 6–12 % of cases the ovarian arteries originate directly from the renal arteries, particularly from accessory renal arteries and most commonly from the right (Shoja et al. 2007). In cases where the ovarian artery comes off an accessory renal artery, associated anomalies, such as a common trunk to supply the adrenal gland or replacement of the inferior phrenic artery has been described (Notkovich 1956; Rahman et al. 1993). Seldomly, an ovarian artery may arise in an aberrant fashion from the inferior mesenteric artery (Smoger et al. 2010; Dixon et al. 2012), the common iliac (Kim et al. 2013), external iliac artery (Kwon et al. 2013), or internal iliac artery (Reed and McLucas 2012). The ovarian artery descends retroperitoneally on the psoas muscle, gives branches to the retroperitoneum (Fig. 2) and ureter, which it crosses anteriorly, and can be identified by its characteristical serpentinous (“corkscrew”) distal segment before it enters the pelvis (Frates 1969). The ovarian artery then courses medially in the suspensory ligament of the ovary (Syn.: infundibulo pelvic ligament) toward the uterine cornu and gives of branches to the ovary on its lateral border. The tubal branch of the ovarian artery supplies the fallopian tube and variable anastomoses with the uterine artery (uterine-to-ovarian artery anastomoses), lateral and inferior to the junction of the uterine body, and to the fallopian tube (Sieunarine et al. 2005).

Fig. 2

Selective angiography of the right ovarian artery shows small branches to the retroperioneum (black arrow) and filling of the perifibroid plexus vessels of a leiomyoma

3 Classification of the Uterine-to-Ovarian Artery Anastomoses

Razavi proposed a classification of the ovarian artery-to-uterine artery anastomoses (Syn.: uterine-to-ovarian artery anastomoses, UOA) distinguishing three patterns based on selective angiography (Razavi et al. 2002).

According to this classification, a Type I pattern describes an ovarian artery that connects to the intramural uterine artery before branches supply the fibroid(s). Type I can be further subdivided into a Type Ia and Type Ib. In Type Ia, the ovarian artery is a major source of blood supply to the fibroids by means of anastomosis with the intramural uterine artery. In these cases, the flow is toward the uterus, without evidence of retrograde reflux in the direction of the ovary on selective uterine artery angiograms. In Type Ib, the ovarian artery supplies the fibroids in a similar manner as in type Ia. Flow is toward the uterus; however, reflux into the ovarian artery is seen on the selective uterine artery angiogram. In Type II, the ovarian artery supplies the fibroids directly. Although anastomoses to the intramural uterine artery may exist, the flow to the fibroids is anatomically independent of the uterine artery. In Type III, flow is continuous toward the ovary on selective uterine angiograms and washout of the contrast material does not occur from the direction of the ovary within the anastomosis. Theoretically, clinical failure after UAE is likely in patients with Type II and is possible in patients with Type I utero-ovarian anastomosis, whereas those with Type III may rather bear the risk of inadvertent (nontarget) ovarian embolization with resulting ovarian failure. It has to be kept in mind that the uterine-to-ovarian anastomosis has been directly observed in only 40–50 % of cases undergoing UAE using selective uterine artery angiography, while anastomoses between ovarian branches of the ovarian and uterine arteries have been observed in a constant fashion in cadaveric studies employing injection of contrast media under X-ray (Razavi et al. 2002; Kozik 2000; Kim et al. 2006).

Moreover, this classification does not include the anatomic relationship between uterus, fallopian tube, and ovary with variant supply of the fallopian tube which is part of the uterine artery-to-ovarian anastomosis (Dubreuil-Chambardel 1925). This calls into question if standard angiography is sufficient and reliable to visualize this vascular connection. The frequency of the types and the significance of these patterns, as described by Razavi et al., and the impact on fibroid perfusion as well as ovarian function is still debated. In a large study including 202 patients undergoing UAE for symptomatic fibroids Lanciego et al. did not find an association between clinical outcomes and any of the types of ovarian artery-to-uterine artery anastomoses (Lanciego et al. 2012). Other factors, such as patient age, may be far more important to ovarian function than visibility and type of ovarian artery-to-uterine artery anastomoses identified on an arteriogram during UAE (Hu et al. 2011) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Angiographic classification of Ovarian-to-Uterine Artery Anastomoses according to Razavi et al. based on selective uterine artery angiogram as well as pre- and post-UAE flush aortography

Type I | The ovarian artery is a major source of blood supply to the fibroids by means of anastomosis with the intramural uterine artery |

Type Ia | Flow within the anastomosis is toward the uterus. No evidence of retrograde reflux in the direction of the ovary on selective uterine artery angiograms |

Type Ib | Flow within the anastomosis is toward the uterus but reflux into the ovarian artery is seen on pre-embolization selective uterine artery angiograms |

Type II | The ovarian artery supplies the fibroid(s) directly |

Type III | Flow in the anastomosis is continuously toward the ovary with an ovarian blush on selective uterine artery angiograms. Wash out occurs in the direction of the ovary |

4 Uterine Artery-to-Ovarian Artery Anastomoses, Ovarian Perfusion, and Function in the Setting of UAE

Several articles address the role of the uterine artery-to-ovarian artery anastomoses in the setting of UAE with respect to subsequent ovarian function. Given the fact that embolic particles can reach the ovary via this anastomosis, the type of anastomosis, the flow direction during embolization, and the size of particles may contribute to the extent of nontarget embolization of ovarian stroma and subsequent reduction of ovarian function (Payne et al. 2002). It has been postulated that larger sized particles may prevent nontarget embolization of the ovary but this has not been substantiated in further studies. Coil embolization of prominent uterine artery-to-ovarian artery anastomosis has been proposed as a measure to prevent premature ovarian failure (Marx et al. 2003). This approach is possible only in a minority of cases where the anastomosis can be reached without difficulties and creating spasm.

Ryu et al. assessed the delayed effects of uterine artery embolization on ovarian arterial perfusion by performing ovarian sonography immediately before and after UAE, as well as several months later. They showed that although persistent loss of detectable arterial perfusion after UAE occurs in some women, most patients reestablish arterial perfusion and do not develop symptoms of ovarian failure (Ryu et al. 2003).

Kim et al. reported in a cohort of 124 women (mean age, 43.1 ± 5.7 years) undergoing UAE for symptomatic fibroids patent anastomoses between the uterine and ovarian arteries in 55 patients (44.4 %) detected by angiography (Kim et al. 2006). Changes in basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level obtained on day three of the menstrual cycle before and 6 months after uterine artery embolization (UAE) were more frequent in women with observed patent anastomoses but also highly age dependent. Salazar et al. compared the incidences of symptom recurrence and permanent amenorrhea following uterine artery embolization (UAE) for symptomatic fibroid tumors in patients with Type I and II utero-ovarian anastomoses with versus without supplemented ovarian artery embolization (OAE) and did not find a significant difference regarding permanent amenorrhea rates but higher symptom recurrence rates were observed when OAE was not performed in the setting of UOA (Salazar et al. 2013) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Selective angiography of the left ovarian artery shows collateral perfusion of the uterus. Opacification of vessels supplying the left ovary (black arrow) is also noted

Although a plethora of prospective studies have been undertaken to assess the relation between UAE and ovarian function by using hormonal assays and ultrasound measurements, only three of these were comparative studies comparing UAE to surgical treatments such as myomectomy or Hysterectomy. These studies show no differences in FSH level between the treatment groups (Salazar et al. 2013; Healey et al. 2004; Hovsepian et al. 2006; Tropeano et al. 2010). Two studies including the randomized EMMY trial comparing UAE to hysterectomy showed, however, a decrease in anti-mullerian-hormone (AMH), a marker which is cycle independent and considered more sensitive to test the extent of ovarian reserve (Healey et al. 2004; Hehenkamp et al. 2007). Ovarian reserve is a term used to describe the functional potential of the ovary and reflects the number and quality of oocytes within it. To evaluate the extent of ovarian reserve reduction, day three FSH is of limited value since it is an indirect marker, reflecting the hormonal balance between the ovaries and the hypothalamo-pituitary axis and large intercycle variations in basal FSH occur (Maheshwari et al. 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree