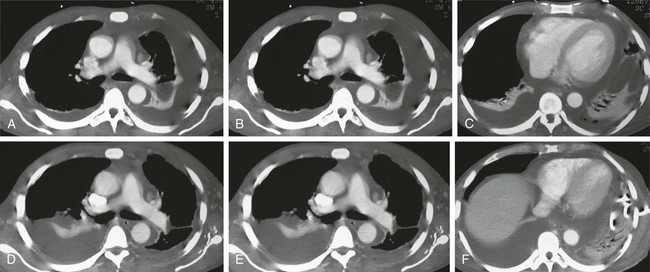

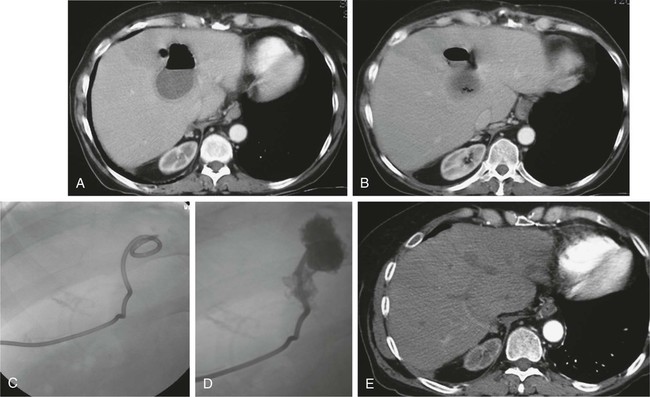

Robert J. Lewandowski, Sudhen B. Desai and Albert A. Nemcek, Jr. Percutaneous management of thoracic and abdominal fluid collections, including pleural effusions and abscesses, has become standard of care in many clinical scenarios.1 This shift from operative management has been facilitated by advances in quality and rapidity of cross-sectional imaging and interventional radiology technology. Percutaneous management of effusions and abscesses is cost-effective and decreases both morbidity and mortality compared with alternative treatments.2–8 To be truly effective, the interventional radiologist must participate in the clinical care of the patient and coordinate care with referring medical and surgical colleagues. To allow percutaneous therapy, the abnormal fluid collection must be clearly visualized on imaging, and there must be an acceptable path from a skin entry site to the abnormality. Although it is often necessary and acceptable to place a needle or catheter through normal organ parenchyma when managing an intraparenchymal abscess, it is often unacceptable to traverse an uninvolved organ or normal bowel. However, some have argued for the benefits of transgastric drainage, and normal hepatic parenchyma may be transgressed if it is the only route to the fluid collection.9 It is sometimes possible to create a more direct and safer access route to the target fluid by injecting saline, lidocaine, or CO2 into the intervening tissues.10,11 This may displace potential obstacles out of the way, but it also may make the target less conspicuous on imaging. Manual compression of tissues with the ultrasound probe may help displace intervening bowel loops, and alternative patient positioning may help clear a potential passageway. It should be noted that a referring surgeon may accept traversal of diseased bowel if an operation is impending. All patients being considered for percutaneous intervention should have their coagulation profile evaluated, including platelet counts, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio (INR), and partial thromboplastin time. Although it is difficult to give strict coagulation parameters, the platelet count should be greater than 50,000 and the INR should be 1.5 or lower.12 All abnormalities are best corrected in conjunction with the referring service. Some patients will need platelet transfusion, fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K, protamine, or other strategies to make the procedure safer.13 The medication administration record should also be reviewed. Specifically, drugs such as aspirin, heparin, subcutaneous heparin, and clopidogrel (Plavix) should be sought because they may increase the risk for a hemorrhagic complication without significantly altering the patient’s coagulation profile. Ideally these medications are stopped for a defined period (aspirin and Plavix, 1 week; subcutaneous heparin, 12 hours; intravenous heparin, 2 hours) before percutaneous intervention,14 but each case must be considered individually. Pleural effusions have many causes and can usually be aspirated (thoracentesis) for symptom relief. Malignant pleural effusions tend to recur rapidly, however, and some special strategies are used to deal with these. A reasonable management plan is to place a tunneled drainage catheter (e.g., Denver Pleurx catheter [Denver Biomaterials, Golden, Colo.]) and monitor the patient on an outpatient basis. Autopleurodesis has been shown to occur in 40% to 50% of these patients.15 If pleurodesis does not occur, a sclerosing agent may be used to scar the parietal and visceral pleural layers together. Such agents include talc, bleomycin, and tetracycline/doxycycline.16,17 Infected pleural fluid collections typically result from pneumonia or are posttraumatic in nature (Fig. 153-1). They can often be successfully managed percutaneously with drains. Infusion of thrombolytic agents into these drains has been used to eradicate the fibrinous components of the inflammatory process.18,19 Lung abscesses are typically secondary to aspiration, hematogenous spread of infection, or spread from an adjacent inflammatory process. More than 80% of lung abscesses respond to the traditional therapy of antibiotics and bronchial lavage. In patients who fail such therapy, percutaneous management may be an alternative to thoracotomy.7,20 A risk of placing a percutaneous drain in the lung is creation of a bronchopleural fistula. Minimizing drainage catheter size and avoiding traversal of normal lung help minimize this risk. Interventional radiologists may be asked to drain pericardial fluid. In our experience, this is best approached with ultrasound guidance. Percutaneous creation of a pericardial window with an angioplasty balloon is a safe therapeutic option, particularly in patients with symptomatic malignant effusions.21 Pyogenic hepatic abscesses are most frequently sequelae of previous hepatic or biliary surgery, but they may also result from trauma, an infectious process elsewhere in the abdomen (e.g., diverticulitis), or an existing hepatic malignancy (Fig. 153-2). Percutaneous management of these abscesses is quite effective for both pyogenic and amebic hepatic abscesses.22,23 A subcostal approach is preferred because it is less painful and there is less chance of crossing the pleural space and causing empyema. The intercostal approach is reserved for instances where a subcostal approach is not possible. It should be noted that although drainage of hydatid (echinococcal) hepatic cysts was once considered a contraindication because of the risk of sepsis, the literature now supports percutaneous management. Hypertonic saline can be injected into the cystic cavities as a scolicidal agent.24

Treatment of Effusions and Abscesses

Contraindications

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Thoracic

Pleural Effusions

Empyema

Lung Abscess

Pericardial Effusions

Abdominal

Hepatic