Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of the Joints

Synovial (osteo)chondromatosis (also known as synovial chondromatosis or synovial chondrometaplasia) is an uncommon benign disorder marked by the metaplastic proliferation of multiple cartilaginous nodules in the synovial membrane of the joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths. This condition was discussed in Chapter 3 under the heading of benign cartilage-forming (chondrogenic) lesions. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), also known as diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumor, is a locally destructive fibrohistiocytic proliferation, characterized by many villous and nodular synovial protrusions, which affects the joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths. This condition can be diffuse or localized. When the entire synovium of the joint is affected, the condition is referred to as diffuse PVNS. When a discrete intra-articular mass is present, the condition is called localized PVNS. When the process affects the tendon sheaths, it is called localized giant cell tumor of the tendon sheaths, nodular tenosynovitis, or according to the recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification, tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Synovial hemangioma, a rare benign lesion whose pathogenesis is still unclear (although some investigators suggest it is a form of vascular malformation), commonly affects the knee joint, although the other articulations such as the elbow, wrist, and ankle may also be the site of this disorder. Lipoma arborescens, also known as villous lipomatous proliferation of the synovial membranes, is a rare intra-articular disorder characterized by a nonneoplastic lipomatous proliferation of the synovium. The term “arborescens” describes the characteristic tree-like morphology of the lesion, which resembles a frond-like mass. Synovial sarcoma (also known as synovioma) is an uncommon malignant mesenchymal neoplasm, that despite its name, does not arise from the synovium. It occurs mainly in paraarticular regions close to the joint capsules, bursae, and tendon sheaths. Synovial chondrosarcoma is a rare tumor that originates from the synovial membrane. It may arise as a primary synovial tumor or it may develop as a malignant transformation of synovial (osteo)chondromatosis.

A. BENIGN JOINT LESIONS

Synovial (Osteo)Chondromatosis

This condition marked by the metaplastic proliferation of multiple cartilaginous nodules in the synovial membrane was discussed in Chapter 3.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS, Diffuse-Type Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor)

Definition:

Locally destructive fibrohistiocytic proliferation characterized by multiple villous and nodular synovial protrusions composed of synovial-like mononuclear cells admixed with multinucleated giant cells, foam cells, siderophages, and inflammatory cells.

Epidemiology:

Young and middle-aged individuals are most commonly affected, with peak incidence in the third and fourth decades.

Male-to-female ratio of 1:2.

Sites of Involvement:

Most common site is the knee joint (75%); less frequently affected are the hip (15%), ankle, wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints.

Clinical Findings:

Slowly progressing process that manifests by mild pain, joint swelling, and limitation of movements in the affected joint.

Duration of symptoms may range from 6 months to as long as 25 years.

Imaging:

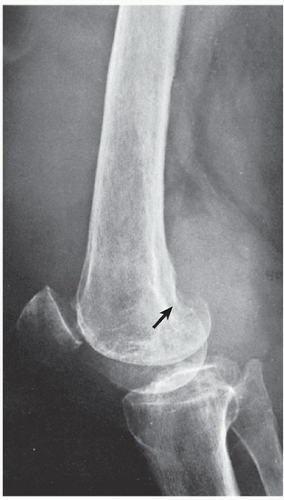

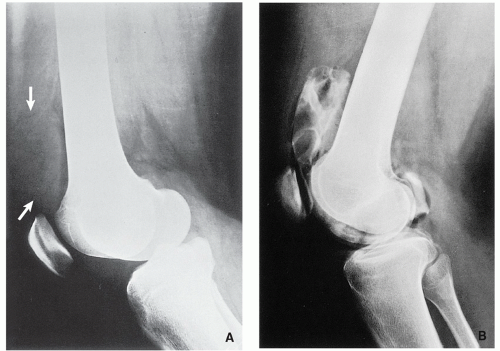

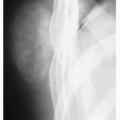

Radiography shows soft-tissue density within the joint greater than expected with joint effusion; occasionally, lobulated soft-tissue mass can be present (Fig. 8.1). Marginal, well-defined erosions of subchondral bone with sclerotic margin on both sides of the joint may be present in about 15% to 50% of cases (see Fig. 8.1). Occasional narrowing of the joint space.

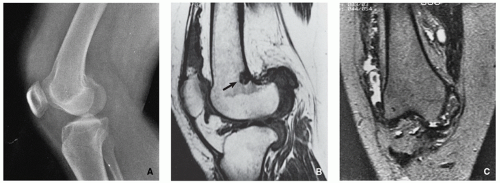

Contrast arthrography demonstrates multiple lobulated masses with villous projections that appear as filling defects in the contrast-filled joint (Fig. 8.2).

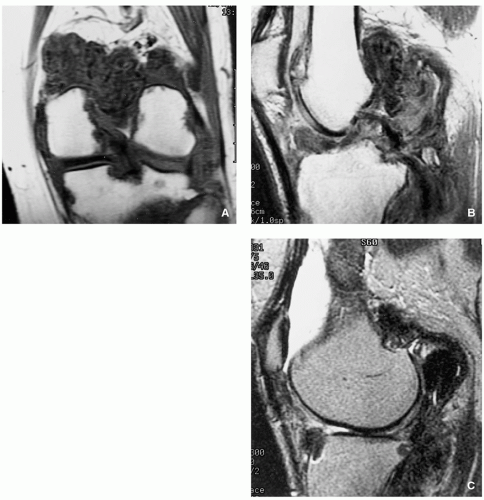

Magnetic resonance imaging features depend on the proportions of hemosiderin, fat, and fibrovascular elements. Generally, high amount of hemosiderin deposition results in low signal intensity of the lesion on both T1- and T2-weighted images. However, most of the intra-articular masses will exhibit a combination of high signal intensity areas representing fluid and congested synovium, interspersed with areas of intermediate-tolow signal intensity secondary to random distribution of hemosiderin in synovium (Figs. 8.3 and 8.4). Low signal intensity on gradient-echo sequences is characteristic. Postcontrast studies show significant enhancement of the lesion.

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

Tan-colored or reddish-brown synovial mass, firm or sponge-like, with hypertrophic villi (Fig. 8.5).

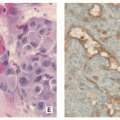

Histopathology:

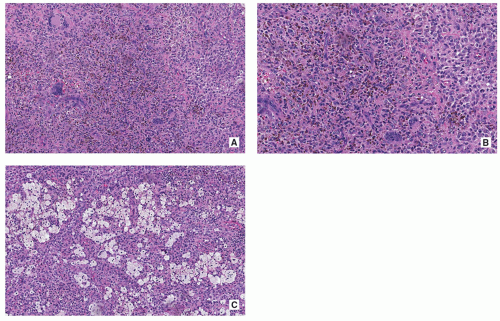

Proliferating collagen-producing polyhedral cells with scattered multinucleated giant cells usually around hemorrhagic foci are commonly present (Fig. 8.6A,B).

Iron deposits and aggregates of foam cells may be present, usually at the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 8.6C).

Dense infiltration of small ovoid or spindle-shaped mononuclear histiocyte-like cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and small ovoid or angulated nuclei commonly displaying longitudinal grooves, accompanied by plasma cells and lymphocytes may be present (Fig. 8.7).

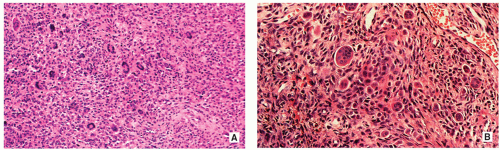

Larger mononuclear cells with kidney-shaped or lobulated nuclei, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with peripheral rim of hemosiderin granules, and occasionally with paranuclear eosinophilic filamentous inclusions (Fig. 8.8).

Mitotic figures are not uncommon.

Variable amount of hemosiderin can be present.

Stroma shows variable degree of fibrosis and hyalinization (Fig. 8.9).

Blood-filled pseudoalveolar spaces may be present.

Extremely rare malignant variant with necrotic areas, significantly increased mitotic rate (more than 20 mitoses/HPF), and spindling of mononuclear cells in myxoid stroma.

Immunohistochemistry:

Positivity for CD68, CD163, CD45, and some cases for CD34.

Genetics:

The translocation t(1;2)(p11;q37) with COL6A3-CSF1 gene fusion.

Rearrangements of the 1p11-13 regions.

Prognosis:

Common recurrence (about 18% to 46%).

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Synovial (osteo)chondromatosis

Radiography usually will show several small uniform in size osteochondral bodies within the joint. MRI will show lack of hemosiderin deposition paramagnetic features.

Histopathology showing the presence of calcified or noncalcified intra-articular chondro-osseous bodies is diagnostic.

▪ Lipoma arborescens

MRI features of fat signal intensity on all sequences are diagnostic.

Histopathology showing features of hyperplasia of subsynovial fat, formation of mature fat cells, and presence of proliferative villous projections is diagnostic.

▪ Synovial hemangioma

Imaging features, and particularly MR images showing intra-articular masses of high signal intensity on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences, with low signal fibrofatty septa, are diagnostic.

Histopathology showing vascular morphology of the lesion, particularly arborizing vascular channels of different sizes is diagnostic.

▪ Hemophilic arthropathy

Imaging studies will show typical changes of joint arthropathy with narrowing of the joint space, articular erosions, epiphyseal overgrowth, and hemarthrosis.

Histopathology showing copious iron deposition and markedly hyperplastic synovium usually limited to the synovial lining cells, together with characteristic clinical features, is diagnostic.

Localized Pigmented Nodular Tenosynovitis (Giant Cell Tumor of the Tendon Sheath, Localized Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor)

Definition:

Well-circumscribed lesion that affects a small area of synovium or the tendon sheath, most commonly occurring in the digits, consisting of mononuclear cells mixed with variable number of multinucleated giant cells, foamy macrophages, and chronic inflammatory cells.

Epidemiology:

May occur at any age but usually between 30 and 50 years.

Slight female predominance.

Sites of Involvement:

Predominantly affecting the digits of the hand (85%).

Less common in the wrist, ankle, foot, or knee.

Clinical Findings:

Painless swelling or mass.

May gradually develop even for several years.

Imaging:

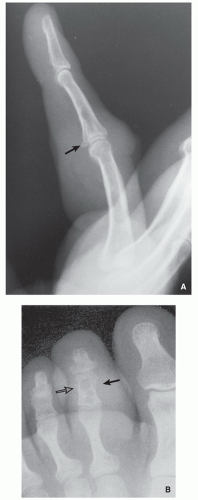

Radiography shows localized well-circumscribed dense soft-tissue mass often associated with osseous erosion (Fig. 8.10).

Magnetic resonance imaging shows in most cases low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences, with strong homogeneous enhancement after administration of gadolinium.

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

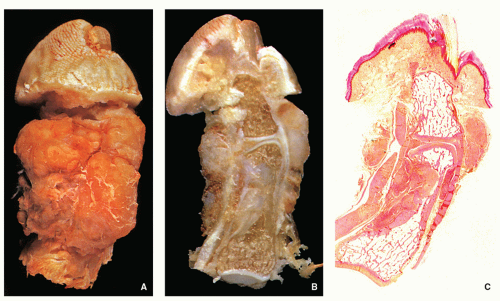

Most lesions are small, up to 4 cm.

Well-circumscribed and lobulated tumor, white-tan to gray in color with yellowish and brown foci, partially encased by a fibrous capsule, may invade the bone or joint (Fig. 8.11).

Histopathology:

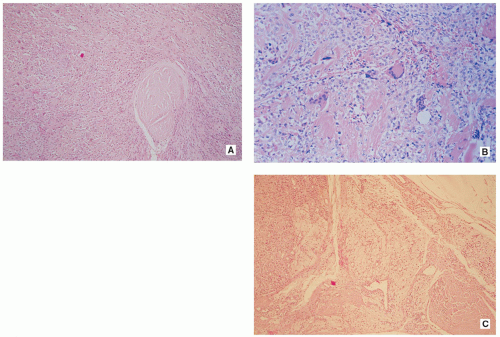

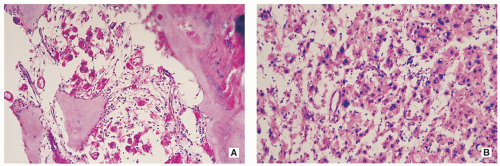

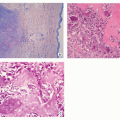

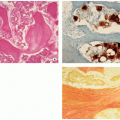

Tissue is composed of different proportions of small, round, or spindle-shaped mononuclear cells with pale cytoplasm and round or kidney-shaped commonly grooved nuclei, osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells, foamy macrophages, and siderophages (Fig. 8.12).

Giant cells contain a variable number of nuclei (from a few to more than 50) and are commonly distributed at the periphery of the tumor (Fig. 8.13).

Larger epithelioid cells with glassy cytoplasm and rounded vesicular nuclei may be present.

Xanthoma cells associated with cholesterol clefts may be seen at the periphery of the tumor.

Hemosiderin deposits are almost always present.

FIGURE 8.11 Gross specimen and histopathology of giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (same patient as presented in Fig. 8.10B). (A) Photograph of the amputated second toe shows a tan tumor encasing the middle phalanx. (B) Sagittal section through the specimen shown in part (A) demonstrates soft-tissue tumor extending around and involving the distal interphalangeal joint. The lesion also invades the medullary cavity of the middle phalanx. (C) Whole-mount sagittal section through the second toe shows the tumor in the soft tissue, bone, and joint space. The pink foci within the tumor tissue represent areas of collagination (phloxine and tartrazine, original magnification ×1). (From Bullough P. Atlas of Orthopedic Pathology with Clinical and Radiologic Correlations. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992, p. 17.25, Figs. 17.70, 17.71, and 17.72).

Stroma may shows variable degree of hyalinization and may occasionally exhibit osteoid-like appearance (Fig. 8.13B).

Mitotic activity usually averages 3 to 5 mitoses per 10 HPF but may reach up to 20/10 HPF.

Immunohistochemistry:

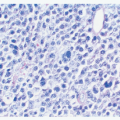

Mononuclear cells expressed positivity for CD68 and CD163.

Multinucleated giant cells are positive for CD68 and CD45.

Genetics:

Same translocation as in diffuse type of tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Prognosis:

Low percentage of local recurrence after surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Enchondroma

Imaging features of radiolucent lesion within the phalanges or metacarpals/metatarsals may occasionally mimic the erosive changes of GCT of the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree