Chapter Outline

Intestinal Complications of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Extraintestinal Complications of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Differential Diagnosis of Colitis

The term inflammatory bowel disease encompasses two forms of chronic, idiopathic intestinal inflammation, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Although many other inflammatory diseases affect the gut, most are distinguished by a specific identifiable causative agent or process or by the nature of the inflammatory activity. The cause of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is unknown, so these disorders are empirically defined by their typical pathologic, radiologic, clinical, endoscopic, and laboratory features. This chapter summarizes the features that usually permit an operational distinction to be made between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The fundamental validity of this classification is uncertain and will remain so until the cause and pathogenesis of these disorders are better understood.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a diffuse inflammatory disease of unknown origin that primarily involves the colorectal mucosa but later extends to other layers of the bowel wall. The disease characteristically begins in the rectum and extends proximally to involve part or all of the colon. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of clinical symptoms and the presence of inflamed mucosa on sigmoidoscopy and confirmed by the findings on barium enema and mucosal biopsy.

Historical Perspective

Although Hippocrates was aware that diarrhea was not a single disease, it required more than 2 millennia before ulcerative colitis was distinguished from the very common infectious enteritides. In 1859, Wilks described the case of Mrs. Isabella Banks, who had “inflammation of the large intestine” and was “affected by discharge of mucus and blood, where, after death, the whole internal surface of the colon presented a highly vascular soft, red surface covered with tenacious mucus, adherent lymph.” By 1900, ulcerative colitis was fully characterized in terms of its clinical and pathologic criteria.

Epidemiology

Epidemiologic data have yielded some important clues concerning the cause of ulcerative colitis. The salient epidemiologic features of ulcerative colitis are listed in Box 57-1 and will be discussed in more detail.

Worldwide prevalence: 35-100 cases/100,000 population

Annual incidence: 2-10 cases/100,000 population

Bimodal age distribution—peak, 15-25 yr; smaller peak, 50-80 yr

Risk factors

White (2-5× risk)

Jewish (2-4× risk)

Live in developed country

Urban dweller

Family history (30-100× risk)

Sibling with disease (8.8% incidence)

Single

Nonsmoker

Ulcerative colitis is more common than Crohn’s disease, with an annual incidence of 2 to 10 cases/100,000 population. The worldwide prevalence ranges from 35 to 100 cases/100,000 population. This wide range is probably the result of true differences in disease distribution as well as differences in reporting, diagnostic criteria, and availability of medical care. The incidence of ulcerative colitis has remained steady. This is in sharp contrast to Crohn’s disease, which has shown a sixfold increase in incidence over the past 3 decades.

Ulcerative colitis is most prevalent in the developed countries of northern Europe, Scandinavia, British Isles, United States, and Israel. The incidence of ulcerative colitis in high-prevalence areas has leveled off, whereas the incidence of Crohn’s disease has been increasing. In low-prevalence geographic areas, the incidence of ulcerative colitis has been increasing. Ulcerative colitis is four times more common in whites than in nonwhites, and there is a slight female preponderance.

There is a twofold to fourfold increase of ulcerative colitis among Jews. The incidence of ulcerative colitis is much lower among Israeli than among American and European Jews. Furthermore, the incidence of disease is lower in Sephardic than in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. These disparate rates suggest that a hereditary predisposition may be altered by environmental factors.

The peak age at onset of ulcerative colitis is between 15 and 25 years of age, with a smaller peak at ages 55 to 65 years. Ulcerative colitis is more common than Crohn’s disease in children younger than 10 years. Ulcerative colitis is more common in urban than in rural populations.

The incidence of ulcerative colitis among first-degree relatives is 30 to 100 times greater than that of the general population. Of patients with ulcerative colitis, 10% to 20% have a similarly affected first-degree relative. The lifetime risk of developing ulcerative colitis among first-degree relatives is 8.9% for offspring, 8.8% for siblings, and 3.5% for parents. The child develops the disease at a much younger age than the affected parent—a phenomenon known as genetic anticipation. Familial ulcerative colitis seems to follow a polygenic inheritance pattern.

The risk of developing ulcerative colitis for current smokers compared with lifetime nonsmokers is 59% less, but the risk is elevated by 64% for former smokers. However, smoking is not therapeutic, and there is no strong evidence of a beneficial effect of smoking on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis. Patients who quit smoking before the onset of disease have more frequent hospitalizations and colectomies. This fact raises the possibility that smoking cessation may lead to more severe illness.

The mortality rate of ulcerative colitis has significantly improved, which can be attributed to improvements in diagnosis and management. In the past, ulcerative colitis was responsible for 90% of deaths attributable to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). More recently, the proportion of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease deaths is about equal—1/100,000 for those 20 to 29 years and 3 to 4/100,000 for those 50 to 59 years of age. Approximately 78% of ulcerative colitis patients die of causes unrelated to bowel disease. Colorectal cancer caused 14% of deaths in ulcerative colitis patients in one study.

Pathogenesis and Causative Factors

Despite exhaustive work by many investigators, the cause of ulcerative colitis is still unknown. Although the participation of genetic, environmental, neural, hormonal, infectious, immunologic, and psychological factors in the pathogenesis of this disease is well established, none of the mechanisms has proved to be the primary causative agent. In addition, it now appears that distal ulcerative proctitis may have a cause different from that of pancolitis.

As noted, familial aggregation of ulcerative colitis is well recognized. The postulated mode of inheritance of susceptibility to ulcerative colitis is through polygenes. The disease occurs with greatest frequency in monozygotic twins. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) phenotypes B5, Bw52, and DR2 also have a significant association with ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis is often associated with the autoimmune disorders, sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, enteropathic oligoarthritis, and anterior uveitis, which are associated with HLA-B27 antigen. Possibly, genes related to ulcerative colitis may encode products that contribute to functional or structural abnormalities in the colon, which render it more susceptible to attack by infection, toxins, and autoimmune actions.

Patients with ulcerative colitis have abnormal mucin production, which may permit various intraluminal bacterial products and toxins to attack the mucosa. It is uncertain whether this defect is a cause or effect of the disease. An infectious cause for IBD with a direct cause and effect relationship between a single microorganism and inflammation still remains plausible. Chlamydia , mycobacteria, gut anaerobes, cytomegalovirus, Yersinia , and bacterial cell wall components have all been implicated as a cause of ulcerative colitis. It is also possible that bacteria that normally constitute normal flora may be pathogenic in a susceptible host.

In ulcerative colitis, the enteric nervous system and nerves containing substance P and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) become straight, thick, and highly immunoreactive. Substance P and VIP are powerful mediators in neurogenically induced inflammation and cause vasodilation, plasma extravasation, and watery diarrhea. All these factors may have a role in the pathophysiology of IBD.

The immune system provides an important contribution to the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis because of failure to clear a microbial or toxic agent or because of an inappropriate response to it. The immune system probably mediates the tissue injury as well, regardless of the trigger, and this is the basis of therapy with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents. The colonic inflammation of ulcerative colitis may merely be an exaggerated physiologic response that is always present within the lamina propria of the colon. There is an alteration of the relative representation of macrophages and T-cell and B-cell populations and an increase in the numbers of immunoglobulin G–bearing cells. The disease is also characterized by a fundamental alteration in antigen-presenting activity associated with a reduction of intestinal suppressor T cells and elevated levels of cytotoxic Leu-7–positive cells. Increased levels of specific antibodies to antigens in the gut lumen are also found. These immunologic disturbances offer great potential for therapy with new immunosuppressive and biologic agents (see later).

Ulcerative colitis is a complex disease. It consists of interactions among initiating organisms or antigens, the host’s immune response, and immunologic, environmental, and hereditary influences.

Findings

Clinical Findings

Ulcerative colitis is highly variable in clinical course, severity, and prognosis. Disease activity waxes and wanes and is characterized by acute exacerbations of bloody diarrhea that resolve spontaneously or after therapy. The most common clinical findings are diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, weight loss, and tenesmus; vomiting, fever, constipation, and arthralgias occur less commonly.

Ulcerative colitis usually behaves as a chronic low-grade illness in most patients. In 15% of patients, this disease has an acute and fulminating course, with explosive diarrhea, hematochezia, and hypotension. Most patients (60%-75%) have intermittent attacks with complete symptomatic remission between attacks, 4% to 10% have one attack and no subsequent symptoms, and 5% to 15% are troubled by continuous symptoms without remission.

Patients with ulcerative proctitis have disease of mild severity, and the disease usually remains distal. There is extension to the proximal colon in 15% of patients over a 10-year period and extension to the hepatic flexure in 7%. At presentation, 30% of patients have disease limited to the rectum, 40% have disease extending above the rectum but not beyond the hepatic flexure, and the remaining 30% have pancolitis. Extraintestinal manifestations, such as arthralgias, mild arthritis, eye inflammation, and rash, are present in fewer than 10% of patients at initial presentation.

Physical examination discloses fever, prostration, dehydration, and postural hypotension in the most severe cases. The abdomen may be protuberant because of colonic atony and distention. Abdominal tenderness over the colon and absent bowel sounds are ominous signs suggesting toxic megacolon or early perforation. Patients with milder involvement present with pallor, low-grade fever, weight loss, and mild abdominal tenderness.

Endoscopic Findings

Sigmoidoscopy is helpful in establishing the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis because the distal colon and rectum are involved in 90% to 95% of cases. Early on, the mucosa is edematous and friable, with loss of the normal vascular pattern and bleeding when touched by the endoscope or rubbed with a cotton swab. With disease progression, granular, spontaneously hemorrhagic mucosa is found, associated with a mucopurulent exudate. The haustra are thick and blunted, the lumen seems narrowed and straightened, and the normal thin (<2 mm) mucosal folds are lost. In severe disease, the mucosa is diffusely hemorrhagic, and frank ulceration with loss of mucosal irregularity is seen.

Radiologic Findings

Plain Abdominal Radiographs.

Considerable information can be gained by carefully scrutinizing the abdominal radiographs of patients with ulcerative colitis. Although attention should be focused on the colon, other abnormalities, such as renal calculi, sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and avascular necrosis of the femoral heads, must also be excluded.

Although the extent of ulcerative colitis is generally determined by barium enema and colonoscopy, these procedures carry a higher risk in severely ill patients. The following radiographic features can be used to assess the severity and extent of the colitis: (1) the extent of formed fecal residue; (2) the appearance of the mucosal edge; (3) alterations of the haustra; (4) colonic width; and (5) mural thickness.

Colonic Fecal Residue.

The distal extent of formed fecal residue provides a good indication, although not absolute, of the proximal extent of the colitis ( Fig. 57-1 ). This approach sometimes overestimates but does not underestimate the extent of disease. The following conclusions can be drawn from the extent of residue :

- 1.

If no residue is visible, the patient probably has active pancolitis.

- 2.

If the residue extends down into the sigmoid colon, proctitis is present (this may be indistinguishable from normal).

- 3.

If residue is present only in the proximal colon, the colitis most likely extends to this level but could be more distal.

- 1.

Mucosa.

The colonic mucosal edge is normally smooth. In active colitis, the line is granular, indistinct, and somewhat fuzzy. With frank ulceration, the mucosal line is disrupted, which causes an irregular edge. With extensive ulceration, only edematous mucosal islands remain. Intramural, mottled-appearing gas shadows may be present in fulminating colitis with necrosis of the bowel wall. Linear pneumatosis suggests extremely deep ulceration or extraperitoneal perforation with gas trapped adjacent to the bowel wall.

Haustration.

Normal haustral clefts run in parallel, about 2 to 4 mm apart, across one third of the diameter of the colon. Widening of the haustral clefts with loss of the parallel lines is an early manifestation of ulcerative colitis and is more obvious on radiographs than the mucosal granularity that it accompanies. The haustra may be completely absent as well. Blunting can be confused with underdistention, so it should not be diagnosed if only a small amount of gas is present within the colon.

Colon Diameter.

The upper limit of normal for the diameter of the transverse colon is 5.5 cm. In chronic, “burned out” ulcerative colitis, the colon becomes tubular and narrowed and is considerably less than 5 cm in diameter. In these patients, if the colon is more than 5 cm in diameter, the inflammation has become transmural, which indicates a fulminant colitis at risk for perforation or toxic megacolon.

Mural Thickness.

In the normal colon, the distance between the line of pericolic fat and gas-filled lumen is less than 3 mm. In chronic ulcerative colitis, it increases to more than 3 mm in thickness. In a study assessing these findings, a combination of four features was pathognomonic for disease proximal to the hepatic flexure: irregularity of the mucosal edge, loss of haustral clefts, increased thickness of the colon wall, and an empty right colon.

Barium Enema

The barium enema has the following roles in patients with ulcerative colitis: (1) to confirm the clinical diagnosis; (2) to assess the extent and severity of disease; (3) to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease and other colitides; (4) to follow the course of disease; and (5) to detect complications. The role of barium enema has largely been supplanted by colonoscopy, multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with ulcerative colitis. The major radiographic findings on the barium enema examination in ulcerative colitis are presented in Box 57-2 ; their anatomic and pathologic origin ( Fig. 57-2 ) and significance are discussed subsequently.

Acute Changes

Mucosal granularity

Mucosal stippling

Collar button ulcers

Haustral thickening or loss

Inflammatory polyps

Confluent, contiguous, circumferential disease

Chronic Changes

Haustral loss

Luminal narrowing

Loss of rectal valves

Widened presacral space

Backwash ileitis

Postinflammatory pseudopolyps

Granular Pattern.

The earliest pathologic changes of ulcerative colitis are hyperemia and the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the mucosa. These changes are manifested by a loss of normal mucosal translucency and obscuration of the submucosal pattern on endoscopy. Subtle thickening of the mucosa or haustral edema may be present radiographically, but these findings are often appreciated only in retrospect. With progressive edema and hyperemia, the mucosa develops a granular pattern ( Fig. 57-3A ). The smooth, sharp, and distinct appearance of the colonic margin seen on normal double-contrast studies is replaced by an amorphous, thickened, and indistinct mucosal line. There is a gradual transition between the normal and abnormal mucosa that extends for several centimeters. This granularity should be distinguished from the granular appearance of chronic ulcerative colitis (see Fig. 57-3B ). In chronic ulcerative colitis, the mucosal surface pattern is coarser, and there are significant changes in colonic contour.

The granular pattern develops as a result of abnormalities in the quality and quantity of mucus produced by the involved mucosa. On histologic examination, there is a reduction in the number of goblet cells, which contain less than the normal complement of mucin. Normal mucus is essential to normal barium coating of the gut. Any process, whether benign or malignant, infectious or inflammatory, that alters mucin production affects mucosal coating and visualization.

Mucosal Stippling.

During the granular phase of ulcerative colitis, inflammatory cells accumulate at the base of the mucosal crypts. Cellular debris tends to block the crypts of Lieberkühn, which leads to the formation of microabscesses, better known as crypt abscesses ( Fig. 57-4A ). These crypt abscesses eventually erode into the lumen. The ulcers deepen, and barium flecks become adherent to them, producing mucosal stippling (see Fig. 57-4B ). This stippling resembles white paint applied by dabbing a surface with the end of a fairly dry paintbrush.

“Collar Button” Ulcers.

With disease progression, the ulcers of the crypt abscess breach the lamina propria and muscularis mucosae and cause undermining of the less resistant areolar tissue of the submucosa. The involved submucosa becomes necrotic, and the ulcers extend laterally, causing further undermining. This undermining is contained by the muscularis propria on the serosal side and by the muscularis mucosae on the luminal side of the colon. The ulcers are frequently related to the taeniae. The mucosal defect is small relative to the degree of undermining and produces a flasklike, so-called collar button ulcer ( Fig. 57-5 ). As these ulcers enlarge and interconnect, the collar button ulcer configuration is lost; a network of residual islands of mucosa and inflammatory pseudopolyps is produced.

Polyps.

A variety of different mucosal protrusions may be seen on barium studies in patients with IBD. Their appearance and significance depend on the stage of disease and pathologic origin.

Inflammatory Pseudopolyps.

In patients with severe ulcerative colitis, there is extensive mucosal and submucosal ulceration in which only small islands of mucosa and submucosa may survive. The inflamed edematous mucosa protrudes above the surrounding areas of ulceration, which gives a polypoid appearance ( Fig. 57-6 ). Because these represent merely the remnants of preexisting mucosa and submucosa rather than new growths, they are termed pseudopolyps. Inflammatory pseudopolyps are the natural progression of collar button ulcers: the ulcers extend and interconnect so that the pseudopolyp rather than the ulcers becomes the major radiographic finding. Inflammatory pseudopolyps usually occur in ulcerative colitis but may also be seen in Crohn’s disease. The cobblestoning pattern seen in Crohn’s disease is another type of pseudopolyp, in which larger islands of preserved mucosa are surrounded by linear and transverse ulcerations.

Postinflammatory Pseudopolyps.

When IBD goes into remission, the denuded mucosa heals and is covered by granulation tissue that has a granular appearance similar to that observed in the early stages of ulcerative colitis. In some patients, the regenerated mucosa has a tendency to overgrow ( Fig. 57-7 ). This overgrowth often results in polypoid lesions that may be small and rounded, long and filiform, or proliferate into a bushlike structure simulating a villous adenoma. Because the regenerating mucosa is cytologically normal, it is not a true neoplasm but a pseudopolyp. Because this occurs during mucosal healing, it is termed a postinflammatory pseudopolyp . These polyps represent the aftermath of a severe attack of colitis and may be the only sign of previous disease. Mucosal bridges are also postinflammatory pseudopolyps, in which a bridge of mucosa survives between islands of mucosa surrounded by ulceration. With remission, the underside of the mucosal bridge and underlying ulcer re-epithelialize.

Postinflammatory pseudopolyps can also be seen after ischemia, after severe infection, and in Crohn’s disease. Filiform polyps have also been described in the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Backwash Ileitis.

In 10% to 40% of patients with chronic ulcerative pancolitis, the distal 5 to 25 cm of ileum is inflamed ( Fig. 57-8 ). This ileitis occurs only in the presence of pancolitis and usually resolves 1 to 2 weeks after colectomy. Although small ulcerations may be present, this is not a primary inflammation of the ileum. The distal ileum can be used to form an ileostomy or pouch. The pathogenesis of this disorder is uncertain but may relate to the reflux of colonic contents into the small bowel, hence the term reflux or backwash ileitis.

Barium studies reveal a chronic pancolitis associated with a patulous and fixed ileocecal valve that easily refluxes and persistent dilation of the terminal ileum. The normal fold pattern is absent, and the mucosa is granular.

Blunting and Lost Haustra.

In the course of ulcerative colitis, the haustral folds undergo two major changes ( Fig. 57-9 ; see also Fig. 57-8 ): (1) early in the disease, they are edematous and thickened; (2) with chronic disease, they become blunted or may be completely lost. This evolution of haustral changes can be understood by a brief review of haustral formation.

At birth, colonic haustra are usually absent, which explains why it is difficult to differentiate colonic from small bowel gas in neonates. As the colon grows, the circular muscle of the muscularis propria outgrows the longitudinal muscle, the taeniae coli. This differential growth rate causes the taeniae to shorten the colon in an accordion-like fashion, with production of saccular haustra that usually are first seen by the age of 3 years.

Haustra are fixed anatomic landmarks in the proximal colon because the circular muscle is fused to the taeniae. In the distal colon, haustra are created by active contraction of the taeniae. Consequently, the colon can normally be devoid of haustra distal to the midtransverse colon; loss of haustra in the proximal colon is always abnormal.

In early ulcerative colitis, the haustra are deformed and thickened because of edema and may produce a corrugate outline to the colon, which has been called the indenture sign. In chronic ulcerative colitis, the haustra are often lost for two reasons, alterations in the muscle tone of the taeniae and the fact that the colon is shortened. In this disease, the taeniae coli become relaxed for some unknown reason. This relaxation is associated with abolition of the haustral pattern. With healing, the haustra may reappear as they gain tone. A second major factor is also at work in chronic ulcerative colitis—massive hypertrophy and fixed contraction of the muscularis mucosae ( Fig. 57-10 ), which causes foreshortening of the colon. Thus, the normal accordion-like array of colon on the relatively shorter taeniae is lost.

Widened Presacral Space.

When the rectum is distended, the retrorectal space as projected on true lateral films obtained during barium enema is usually 7.5 mm or less. A distance of 1 to 1.5 cm is considered a moderate increase of this space, and a distance greater than 1.5 cm is abnormal. These values are obtained by measuring the shortest distance between the posterior edge of the barium column and the anterior edge of the second sacral segment. The presacral space is frequently widened in chronic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease but may also be seen in obese patients and patients with pelvic lipomatosis, pelvic carcinomatosis, radiation fibrosis, inferior vena cava thrombosis, sacral and rectal tumors, chlamydial infection, and other infectious proctitides.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, two processes account for the abnormal presacral space (see Fig. 57-10 ): (1) narrowing of the rectal lumen and its associated mural thickening; and (2) proliferation, inflammation, and infiltration of perirectal fat. These changes are well demonstrated by CT and correlate with the edematous adipose tissue and enlarged perirectal lymph nodes that are commonly observed at the time of abdominoperineal resection in patients with ulcerative colitis. In patients with Crohn’s disease, perirectal abscesses may also contribute to this widening.

Rectal Valve Abnormalities.

At least one rectal valve should be visible on lateral rectal views of double-contrast enemas. The fold is usually seen at the level of S3 and S4 and should be less than 5 mm thick. The rectal valves are an important indicator of proctitis and should be interpreted with the size of the presacral space. Two situations are indicative of proctitis:

- 1.

The presacral space is more than 1.5 cm, with the valve thicker than 6.5 mm or absent.

- 2.

The presacral space is normal, but the valve thickness is more than 6.5 mm.

Strictures.

Benign strictures are local sequelae of ulcerative colitis that occur in approximately 10% of patients. They are usually localized and smoothly tapering and are only rarely sufficiently narrow to cause obstruction. They are sometimes reversible and are usually found in the distal colon. Strictures that are not reversible and are located more proximally in the colon should be viewed with suspicion for a neoplasm. The strictures have been attributed to the changes of the muscularis mucosae described earlier and are almost invariably associated with mural thickening on cross-sectional imaging.

Distribution.

Ulcerative colitis originates in the rectum and extends proximally in a continuous fashion. There is often a fairly sharply defined margin between diseased and normal bowel. The affected mucosa is diffusely, contiguously, confluently, circumferentially, and symmetrically involved, without normal intervening mucosa. The rectum is almost invariably involved but may be spared in patients treated with corticosteroid enemas.

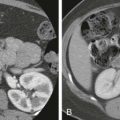

Computed Tomography

The subtle mucosal abnormalities that characterize the early stages of ulcerative colitis are beneath the spatial resolution of CT. With progressive disease, severe mucosal ulceration can denude certain portions of the colonic wall, leading to inflammatory pseudopolyps ( Fig. 57-11 ). When sufficiently large, these pseudopolyps can be visualized on CT. Mural thinning, unsuspected perforations, and pneumatosis can be detected on CT in patients with toxic megacolon. In this regard, CT can be quite helpful in determining the urgency of surgery in patients with stable abdominal radiographs but a deteriorating clinical course. Postinflammatory pseudopolyps can also be seen on CT.

Mural thickening and luminal narrowing are common CT features of subacute and chronic ulcerative colitis ( Fig. 57-12 ; Box 57-3 ). The mucosa becomes thickened because of hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosae in chronic ulcerative colitis. Also, the lamina propria is thickened because of round cell infiltration in acute and chronic ulcerative colitis. The submucosa becomes thickened because of the deposition of fat or, in acute and subacute cases, edema. Submucosal thickening further contributes to luminal narrowing.

Ulcerative Colitis

Mural thickening <1.5 cm

Target appearance of wall—submucosal edema (acute)

Target appearance of wall—submucosal fat (chronic)

Increased perirectal and presacral fat

Crohn’s Disease

Mural thickening >2 cm

Target appearance of wall—submucosal edema (acute)

Target appearance of wall—submucosal fat (chronic)

Homogeneous CT density of wall

Mural thickening of small bowel

Abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts

Mesenteric changes (abscess, phlegmon, fibrofatty proliferation)

Perianal disease

Common Findings

Mural thickening

Narrowed lumen

Increased lymph node size and number

On CT, these mural changes produce a target or halo appearance when axially imaged. The lumen is surrounded by a ring of soft tissue density (mucosa, lamina propria, hypertrophied muscularis mucosae), surrounded by a low-density ring (edema or fatty infiltration of the submucosa), which in turn is surrounded by a ring of soft tissue density (muscularis propria). This mural stratification is not specific and can also be seen in patients with Crohn’s disease, infectious enterocolitis, pseudomembranous colitis, ischemic and radiation enterocolitis, mesenteric venous thrombosis, bowel edema, and graft-versus-host disease.

Rectal narrowing and widening of the presacral space are radiologic hallmarks of chronic ulcerative colitis. MDCT depicts the anatomic alterations that underlie these rather dramatic morphologic changes (see Fig. 57-10 ). The rectal lumen is narrowed because of the mural thickening that attends chronic ulcerative colitis (see earlier). As a result, the rectum has a target appearance on axial scans, which should not be mistaken for the external anal sphincter, mucosal prolapse, or levator ani muscles. The increase in the presacral space is caused by proliferation of the perirectal fat.

Ultrasonography

IBD alters the thickness and echogenicity of the gut wall or individual layers, integrity of mural stratification, appearance of surrounding tissues, and bowel motility and compressibility ( Box 57-4 ). Edema is a prominent feature of acute intestinal inflammation. Edema results in thickening of the colon wall and preservation of wall stratification ( Fig. 57-13 ). On transverse section, alternate hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers give rise to a target appearance. In ulcerative colitis, the mucosa becomes thickened and hypoechoic as a result of edema. The submucosa also thickens, but colonic motility is maintained. With progressive disease, haustral septations are lost. In patients with well-established disease, bowel wall thickness is approximately 0.6 ± 0.2 cm. In one series, these changes were seen in all patients with pancolitis, in 94% of those with left-sided colitis, but in only 50% of patients with rectosigmoiditis. If there is extensive pseudopolyposis, the thickness of the wall may increase to 1.5 cm, which is often accompanied by loss of wall stratification.

Ulcerative Colitis

Moderately thick, hypoechoic wall

Typical wall stratification maintained

Loss of haustration

Absent peristaltic motion

Crohn’s Colitis

Clearly thickened, hypoechoic wall

Loss of typical wall stratification

Loss of haustration

Diminished compressibility

Absent peristaltic motion

Increased blood flow of superior mesenteric artery with decreased resistive index

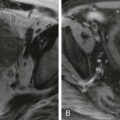

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging is capable of identifying the mural stratification present in ulcerative colitis ( Figs. 57-14 and 57-15 ). MRI demonstrates thickening and abnormal hypointensity of the mucosal and submucosal layers on T1- and T2-weighted images. The T1 shortening probably relates to the severe hemorrhagic phenomena that frequently appear in these layers. The degree of mural enhancement correlates well with the severity of disease activity on fat-suppressed gradient-echo images after the intravenous (IV) administration of gadolinium.

Scintigraphy

Although the diagnosis and assessment of disease activity of ulcerative colitis are made primarily by radiographic and endoscopic techniques, both gallium 67 ( Ga) citrate and indium 111 ( In)–labeled leukocyte scans have proved helpful for patients with IBD. Scintigraphic techniques are useful when there is danger of bowel perforation and the extent and degree of disease activity must be assessed. Positron emission tomography (PET) using F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) can also be used to assess disease activity. FDG uptake ( Fig. 57-16 ) is increased in areas of active inflammation resulting from hyperemia and increased metabolic activity.

Therapy

Medical Management

The treatment of ulcerative colitis depends on the severity, extent, and distribution of disease. Sulfasalazine, a congener of 5-aminosalicylic acid and sulfapyridine, is effective in the treatment of acute ulcerative colitis and in reducing the frequency and severity of recurrent attacks. Sulfasalazine attenuates the bowel inflammation by a number of actions: (1) reduces production of prostaglandins; (2) diminishes leukotriene production, which activates neutrophils and other constituents of the inflammatory response; (3) blocks the chemotactic activity of formulated bacterial peptides that help recruit neutrophils to the bowel; and (4) acts as a scavenger of oxygen free radicals. Many patients develop hypersensitivity or less specific forms of intolerance; efforts are now being made to deliver the active component, 5-aminosalicylic acid, without the sulfapyridine moiety, which apparently causes the hypersensitivity.

Corticosteroids are effective in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. They do not affect the rate or timing of disease recurrence in patients in remission. Topical hydrocortisone in the form of a foam enema is the mainstay of therapy for distal proctocolitis.

Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil), methotrexate, and cyclosporine are alternative therapies in patients with refractory disease. Bowel rest and nutritional therapy also have beneficial effects on this disease.

Increased concentrations of leukotrienes in the inflamed mucosa in ulcerative colitis have suggested the use of inhibitors of leukotriene B 4 (LTB 4 ) for therapy because this is a highly potent mediator of inflammation. LTB 4 receptor antagonists are under investigation as are inhibitors of platelet-activating factor and mast cell stabilizers.

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as Remicade and Humira suppress part of the inflammatory response of IBD. Although used more commonly in patients with Crohn’s disease, these agents have been found useful for patients with ulcerative colitis.

Surgery

Although proctocolectomy is always curative for ulcerative colitis, this procedure carries an operative risk, and not all patients are willing to accept an ileostomy. Consequently, colectomy is not indicated for patients who are easily managed medically. There are several major indications for surgery in ulcerative colitis: (1) massive, unremitting colonic hemorrhage; (2) toxic megacolon with impending or frank perforation; (3) fulminant colitis that is unresponsive to antibiotic, supportive immunosuppressive therapy; (4) obstruction from a stricture; and (5) suspicion or demonstration of colon cancer. Less immediate and definite indications for colectomy are (1) intractable chronic disease that becomes a physical and social burden to the patient and is unresponsive to appropriate therapy, (2) failure of children to mature at an acceptable rate, and (3) high-grade dysplasia in a patient with pancolitis. Fulminant acute disease accounts for 13% to 25% of colectomies in patients with ulcerative colitis. Many of the extraintestinal complications of ulcerative colitis, such as uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum, are also eliminated by colectomy. However, the course of hepatobiliary disease and ankylosing spondylitis is usually not altered by surgery. Since the 1980s, tremendous advances have been made in the surgical approach to ulcerative colitis that offer the patient and surgeon a variety of options.

Proctocolectomy with a Brooke Ileostomy.

After a proctocolectomy is performed, the end of the ileum is passed through an opening in the middle aspect of the right rectus muscle at a point beneath the umbilicus that allows convenient placement of the forepiece of an ileostomy bag. This procedure is curative and requires one operation, but the patient must constantly wear an external ileostomy appliance that needs to be emptied four to eight times per day. Perineal wound problems, stoma revision, and small bowel obstruction occur in 10% to 25% of patients. This is the fastest and safest operation, but it dramatically alters body image in many patients, particularly younger ones.

Proctocolectomy with Continent Ileostomy (Kock Pouch).

A continent ileostomy is made by creating a pouch out of terminal ileum to hold the intestinal contents, an ileal conduit that leads from the pouch to the stoma, and an intervening intestinal valve. Patients empty the pouch by passing a tube through the valve via the stoma. The ileostomy is continent, so an external appliance is not needed. The nipple valve is created by intussuscepting the terminal ileum in a retrograde manner into the pouch for 3 to 4 cm. Anatomic complications requiring reoperation develop in 40% to 50% of these patients.

Total Colectomy with Ileorectal Anastomosis.

Total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is no longer popular because of a fairly high complication rate and unpredictable functional result.

Total Proctocolectomy, Rectal Mucosal Stripping, and Ileal Pouch Formation with Anastomosis to the Sphincter.

This is the preferred operation in most patients. An abdominal colectomy and mucosal proctectomy are performed. A J pouch or W-shaped pouch is fashioned out of ileum. This reservoir is then anastomosed to the anus ( Fig. 57-17 ). The endorectal ileal pouch and anal anastomosis are given 8 weeks to heal by diverting the gut through a conventional ileostomy. The advantages of this procedure are that no stoma is required and that fecal continence is usually maintained, albeit with bowel movements four to eight times per day.

This procedure is technically demanding and requires two operations. Complications include postoperative abscess, pouch fistulas, stenosis, small bowel obstruction, and pouchitis. Approximately 15% of patients require reoperation, and some ultimately require a conventional ileostomy. Pouchitis is an inflammatory process that can cause tenesmus, bloody diarrhea, and constitutional symptoms similar to those of ulcerative colitis.

Prognosis

The prognosis in ulcerative colitis has improved dramatically. Most patients have mild to moderate disease, and only 15% to 25% require a colectomy. Mortality associated with ulcerative colitis occurs in the first 2 years of disease, primarily in patients older than 40 years—one third attributable to the colonic disease itself, one third caused by complications of the disease (colorectal cancer, sclerosing cholangitis, thromboembolic disease, medical and surgical therapy), and the remaining third attributable to unrelated causes. Excess mortality of 2.1% for men and 1.5% for women has been reported, but only for the first 2 years of disease. Most patients with ulcerative colitis can cope with their disease and achieve what is subjectively interpreted as a relatively acceptable lifestyle.

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, cicatrizing disorder of the alimentary tract characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the mucosa, bowel wall, and surrounding mesentery. Any portion of the alimentary tract may be involved, but the terminal ileum and proximal colon are most frequently diseased.

Historical Perspective

It is difficult to decide who described the first case of “regional ileitis” or “ileocolitis.” In 1806, Combe and Saunders described “a singular case of stricture and thickening of the ileum.” Although similar cases were reported in the 19th century and early years of the 20th century, the first series of satisfactorily documented cases of regional enteritis was described by Crohn, Ginzburg, and Oppenheimer in 1932 at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Crohn’s disease was originally called terminal ileitis because these cases were located mainly in the distal ileum in young persons. The outstanding complaints of the patients were diarrhea and weight loss, with progressive anemia and fever. Pathologic examination showed a thickened intestinal wall with subacute or chronic necrotizing inflammation and a greatly enlarged mesentery. Small linear ulcerations with distorted and broken mucosal folds and a cobblestone appearance were noted. The ulceration of the mucosa was accompanied by a disproportionate connective tissue reaction in the bowel wall, leading to stenosis and multiple fistulas. The lumen was “irregularly encroached” with dilation of proximal areas of the bowel. Many years later, it was realized that Crohn’s disease might be confined to the colon without affecting the ileum; it is now recognized that Crohn’s disease can involve every portion of the gut, from the mouth to the anus.

Pathogenesis and Causative Factors

The cause of Crohn’s disease remains unknown. Although the participation of genetic, environmental, infectious, immunologic, and psychologic factors in the pathogenesis is well established, none of these mechanisms has proved to be the primary causative agent. Genetic vulnerability is likely to facilitate the occurrence of the disease, whereas the other factors may play a supportive and superimposed role. A further complicating factor in establishing a cause is the fact that in practice, Crohn’s disease does not behave as a single disorder.

More recently, interest has centered on immunologic mechanisms, in particular the role of platelet-activating factor. Platelet-activating factor is a form of phosphatidylcholine that causes inflammation that is detectable in colonic mucosa in IBD but is not present in normal colonic mucosa. Production of platelet-activating factor is stimulated by a number of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin and leukotrienes. In vitro studies have demonstrated that levels of several forms of prostaglandin are significantly elevated in the mucosa in Crohn’s colitis and ulcerative colitis. Local release of LTB 4 by the rectal mucosa is considerably increased in ulcerative colitis but is elevated in Crohn’s colitis only when frank ulceration is present. Consequently, safe inhibitors of platelet-activating factor are now being sought, which could prove to be a powerful new form of therapy.

Other immunologic evidence suggests that there is a failure of suppressor cell generation coupled with a hyperactive state of helper T cells in patients with IBD. The activated T cells may then lead to an overactive immune response that is not turned off. This response results in increased macrophage activation, enhanced cytokine production, and augmented antibody secretion. Although immunologic factors are important, no specific antibody-producing antigen has been identified in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBD. Also, there is still no convincing demonstration of any fundamental underlying immune defect. Further evidence against immunodeficiency as the cause of Crohn’s disease comes from the report of a patient who had a prolonged remission coincidental with acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Similarly, exhaustive efforts to relate mycobacterial infection to Crohn’s disease have been unsuccessful. A defect in mucosal permeability that permits absorption of macromolecules and complex sugars may be another important factor in the pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease. Apparently healthy relatives of patients with Crohn’s disease show the same intestinal permeability defect. This finding suggests that this defect may antedate intestinal inflammation and may also play a causative role.

Epidemiology

Although understanding of the epidemiology of Crohn’s disease is unclear, investigators hope that more precise information will yield important clues about cause. Salient epidemiologic features are listed in Box 57-5 .