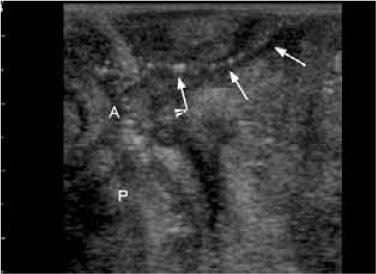

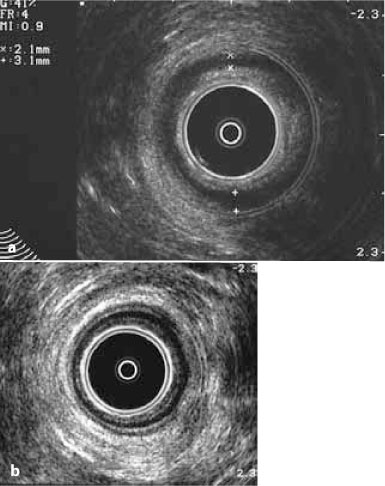

Fig. 13.1

Perianal fistula in a 39-year-old man with ulcerative colitis. Note the hypoechoic area and disruption of the normal wall structure at the site of the internal opening

The fistulas in UC may be difficult to assess, especially in patients with IPAA, in whom the diagnosis and classification of these lesions are hampered by deformation of the pouch-anal anastomosis, defects of the anal sphincters, and the presence of sinuses and folds that may simulate the presence of incomplete perianal fistulas. However, to date, no study has assessed the accuracy of transanal ultrasound in detecting fistulas and abscesses in patients with IPAA.

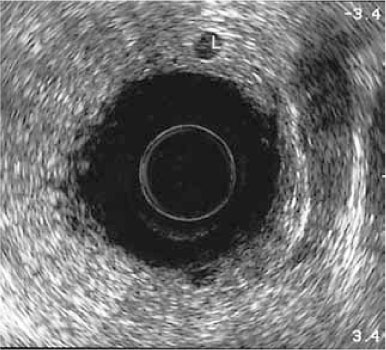

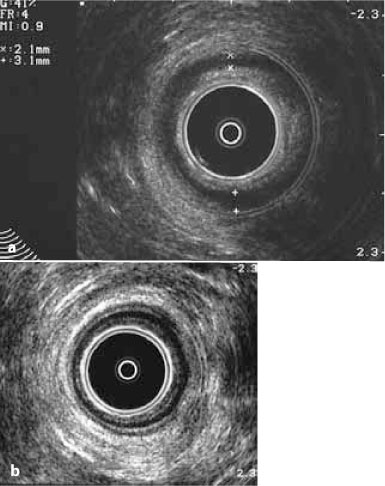

Transanal ultrasound may reveal defects in the anal sphincters and assess wall and peri-pouch changes. A study that quantified the anatomical changes of the anal sphincters after IPAA correlated these findings with anal manometry and fecal incontinence in 23 patients [9]. The results showed that IPAA leads to a reduction in the thickness of the internal anal sphincter (mean 1.16 mm), with tapering or gaps probably caused by direct trauma to the sphincter because of mucosectomy and/or denervation (Fig. 13.2); however, the reduction in the internal anal sphincter thickness did not correlate with continence. In patients with pouchitis, transanal ultrasound may show a variably increased wall thickening, hypertrophy of the peri-pouch fat, and enlarged lymphnodes (Fig. 13.3).

Fig. 13.2

Transanal ultrasound in a 42-year-old man with IPAA for ulcerative colitis. a Note the reduced thickness of the internal and external sphincters compared with b that of the normal anal canal in an age-comparable male patient with ulcerative colitis

Fig. 13.3

A 34-year-old man with pouchitis. Transanal ultrasound shows increased wall thickening, hypertrophy of the peripouch fat, and enlarged lymph-nodes

With the high resolution of transanal ultrasound in imaging the rectal walls and assessing the depth of intestinal inflammation, this technique has been proposed to differentiate UC from CD and infectious colitis, to assess disease activity, and to predict the response to medical treatment and the need for surgery, both in patients with active UC and in those with IPAA.

Preliminary results showed that in UC, rectal wall thickness as assessed by intraluminal sonography using transanal or miniaturized probes in combination with endoscopy correlates with disease activity and may predict both the response to medical therapy and the occurrence of relapse [10,11].

Furthermore, since CD tends to be transmural while UC is a superficial mucosal inflammatory process, hopes were raised that trans-rectal ultrasound would be effective in discriminating cases of otherwise indeterminate colitis. However, such efforts have been largely disappointing [12], although a recent pilot study showed that transrectal ultrasound elastography may be a promising diagnostic tool to differentiate UC from CD. Specifically, the stiffness of the bowel wall, as assessed according to the strain ratio, was shown to better differentiate inflammatory bowel disease than a simple measurement of rectal wall thickness [13], while in a small study the detection of perirectal lymph nodes in patients with nonspecific or suspected infectious colitis was shown to suggest a diagnosis of associated UC or to predict the development of a chronic colitis [14].

13.3 Trans-perineal Ultrasound

Perineal ultrasound can be used to assess the wall of the distal rectum and anorectal junction in the setting of an assessment of a perianal fistula and the function of the pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with IPAA in whom obstructed defecation and fecal incontinence have developed.

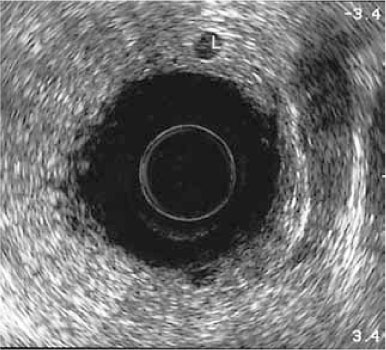

Perineal ultrasound, performed using high-frequency curved microconvex and linear-array probes, assesses fistulous and sinus tracts as well as abscesses and collections, documenting their relationship with the anal canal, the scrotum in men, and the labia and vagina in women. In particular, perineal ultrasound is useful to detect perianal fistulas and inflammatory tissue or masses located outside the field of view of transanal ultrasound, or when the latter exam cannot be performed in a patient with severe anal pain or stricture (Figs. 13.4 and 13.5). Perineal ultrasound can also be employed to differentiate superficial lesions that simulate perianal fistula, such as pilonidal sinus. The latter originates subcutaneously, most likely from a chronic infection of a hair follicle.

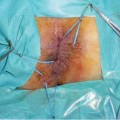

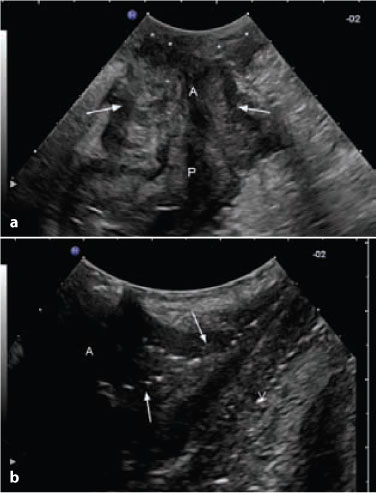

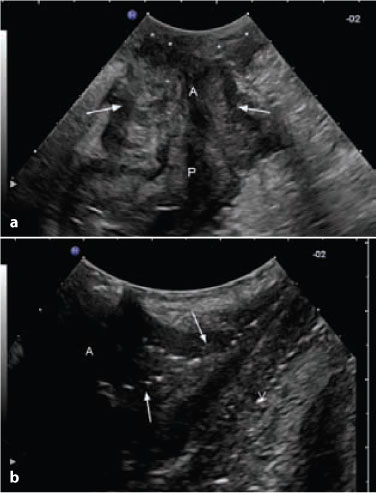

Fig. 13.4

A 25-year-old woman with peripouch inflammatory tissue and pouch fistulas. a Longitudinal perianal ultrasound section, showing peripouch superficial (asterisks) and deep (arrows) inflammatory hypoechoic tissue. b Coronal perianal ultrasound section in the same patients, showing fistulous tracts (arrows) and inflammatory tissue extended to vagina (V). P pouch, A pouch-anal anastomosis