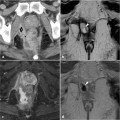

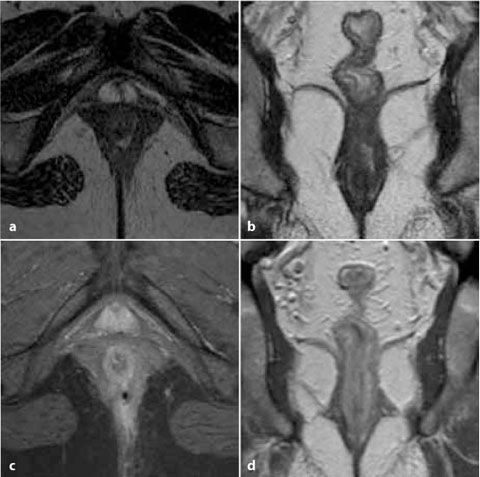

Fig. 23.1

Simple, active intersphincteric fistula in a 34-year-old male with ulcerative colitis without a previous surgical history. Axial T2- weighted (a) image shows a subtle, posteriorly directed, linear T2-hyperintense tract. The corresponding axial fat-suppressed (b) and coronal T1-weighted (c) images reveal linear enhancement after intravenous contrast administration

bidity approaches 70% after 10 years and a non-negligible rate of pouch failure can lead to pouch removal and permanent ileostomy [3–6].

A wide spectrum of pouch-related complications may be encountered, including pouchitis, anastomotic leakages and pelvic abscess collections, perianal or anovaginal fistulas, anal stenosis, and small bowel obstruction [3, 7–9]. Knowledge of surgical procedure details as well as the normal imaging appearance of the ileal pouch reservoir and the possible complications are required for confident interpretation of diagnostic studies in patients treated by IPAA [7].

Based on its wide availability and the very fast acquisition times of current multidetector scanners, CT is the mainstay imaging technique to assess clinically suspected complications during the early postoperative period in patients undergoing IPAA. Intravenous iodinated contrast medium is usually injected, whereas bowel opacification with water-soluble contrast per os or per rectum may prove useful for problem-solving or to rule out anastomotic leakage. At

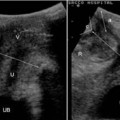

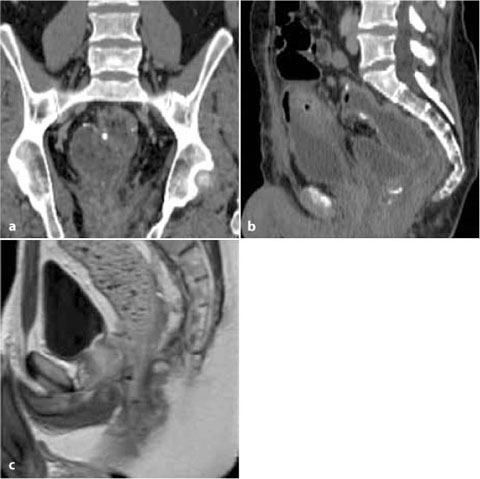

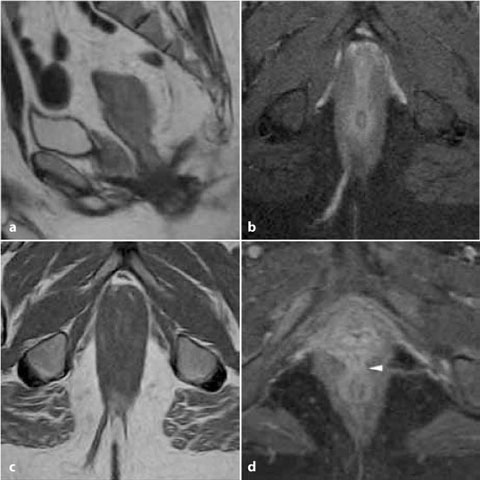

Fig. 23.2

A 40-year-old male with ulcerative colitis undergoing medical treatment. Axial (a) and coronal (b) T2-weighted images reveal an intersphincteric horseshoe-shaped collection. Axial fat- suppressed (c) and coronal (d) T1-weighted imaging after intravenous contrast result in active enhancement of the intersphincteric space and the posterior fistula. Clinical examination confirmed a draining orifice

CT, the ileal pouch reservoir is identified as a fluid-filled structure in the anatomical location of the resected rectum, with metallic surgical staples located 180° to each other. The pouch-anal anastomosis, indicated by the presence of hyperdense clips, should also be identified as its represents a possible source of leakage (Fig. 23.3). CT is reliable in the diagnosis of pouch-related septic complications, suggested by the detection of extraluminal air, fluid, or contrast material [9, 10].

More recently, pelvic MRI has been reported as a very accurate modality for the assessment of postoperative IPAA anatomy and possible complications. MRI is well tolerated even by patients with anal pain or stenosis, as the images

are acquired with external phased-array coils without special patient preparation. The lack of irradiation and limited biologic invasiveness of gadolinium contrast are particularly beneficial in young patients with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, who often need imaging follow-up studies. Other significant advantages of MRI include panoramic and detailed views, a native multiplanar capability, and high contrast resolution [7–9].

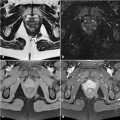

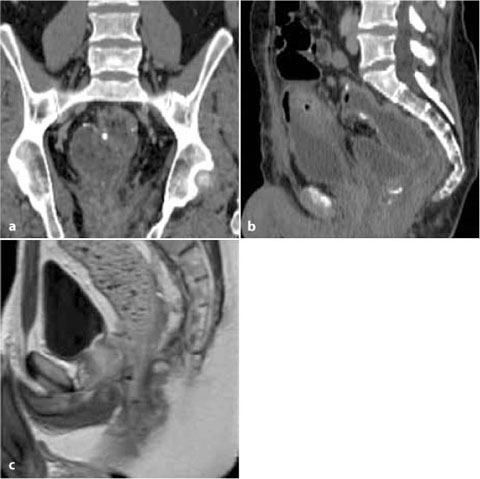

Fig. 23.3

Normal appearances after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Coronal (a) and sagittal (b) CT multiplanar reformations allow identification of the pouch-anal anastomosis and of the normal ileal pouch reservoir as a fluid-filled structure in the rectum; the metallic clips are evident. In another patient, sagittal T2-weighted MRI (c) shows both the distended ileal pouch, with small hypointense foci corresponding to metallic clips in the pouch (cranially), and the ileo-anal anastomosis (caudally)

At MRI, the normal ileal pouch reservoir is identified by the small hypointense ferromagnetic artifacts (signal voids) on all sequences, corresponding to the location of the metallic staples (Fig. 23.3). After IPAA surgery, UC patients may develop perianal fistulizing complications that are indistinguishable from those usually seen in Crohn’s disease (Figs. 23.4, 23.5). Typically, active fistulous tracts appear as fluid-filled hyperintense tubular structures of variable length on high-resolution T2-weighted and STIR images. Abscess collections are easily identified, sometimes with air-fluid levels and mass

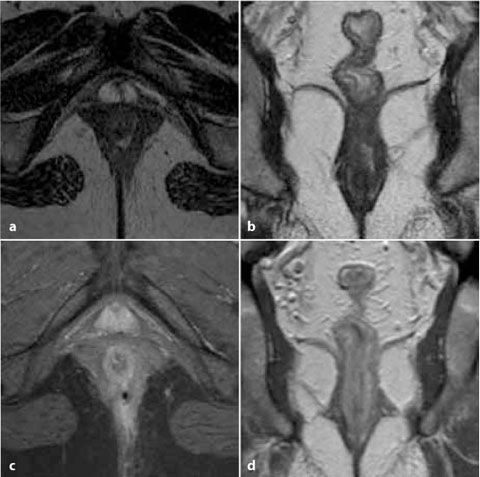

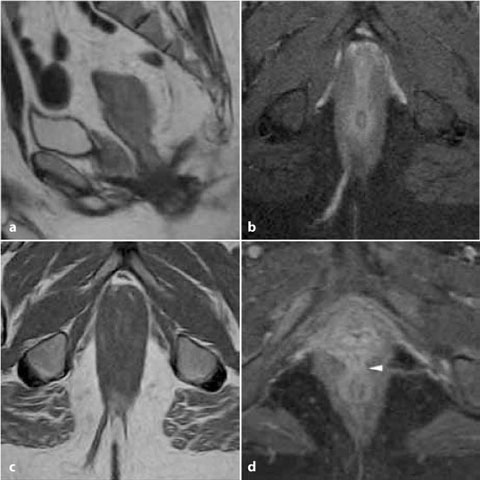

Fig. 23.4

A 47-year-old male patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) treated with IPAA. Sagittal (a) T2-weighted, axial STIR (b) and unenhanced T1-weighted (c) images allow identification of the ileal pouch and of a long, fluid-containing transsphincteric fistula crossing diagonally through the right ischioanal fossa. In another, female patient with UC, the axial contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (d) identifies an anovaginal fistula (arrowhead), clinically suspected due to a complaint of vaginal discharge

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree