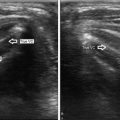

Fig. 23.1

Ultrasound of a midline suprahyoid lobulated cyst, measuring 2 cm, consistent with a thyroglossal duct cyst

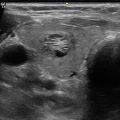

Fig. 23.2

A young man presented with recurrent episodes of infection in this complicated right paramidline infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst with internal debris, measuring 2.4 cm

23.2.2 Dermoid and Epidermoid Cysts and Teratomas

Dermoid and epidermoid cysts and teratomas are classified as dysontogenetic cysts. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts are found in the floor of mouth region and are thought to develop from trapped tissue in embryonic fusion planes. Dermoid cysts are typically found in the second and third decade of life and are midline in nature. The less common epidermoid cysts tend to be found during infancy, but are also found in the suprahyoid midline [1].

Ultrasound can be useful for evaluating these lesions if they are superficial in nature. Deeper cysts are better evaluated with a contrasted CT scan [1]. Superficial dermoid cysts that are evaluable with ultrasound will typically be hypoechoic and thin walled, but can have a heterogeneous appearance due to hair, sebum, or fluid within the lesion [2, 4, 6, 7]. Coalescent fat and calcifications within a dermoid cyst give rise to what is known as a “pseudosolid ” or “sac-of-marbles” appearance, and this is nearly pathognomonic for this lesion [1, 7]. Epidermoid cysts tend to be more homogeneous in appearance due to the lack of dermal appendages [1]. Calcification with visible blood flow is characteristics of a teratoma [2, 8].

23.2.3 Branchial Cleft Abnormalities

Branchial cleft abnormalities include cysts, which are most common, fistulas, and sinuses [2]. The vast majority of branchial cleft abnormalities are from the second branchial arch and are found near the carotid bifurcation [Fig. 23.3]. Those found in the parotid region are more likely from the first arch [1, 2]. Third-arch lesions are most commonly found in the posterior cervical space, while fourth-arch abnormalities are typically adjacent to the left lobe of the thyroid [1]. It is important to perform a careful evaluation for a sinus tract, as this can aide in the operative management of these lesions [2].

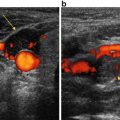

Fig. 23.3

Ultrasound of a large, well-defined avascular mass, suggestive of a branchial cleft cyst type II

Regardless of location, these lesions are hypoechoic or anechoic, thin walled, and compressible [Fig. 23.4]. One can occasionally see sedimentation levels within the fluid, thick cyst walls, or septations, but this is not typical [1, 2, 7, 9]. More frequently these lesions show fine echogenic regions that are secondary to cholesterol crystals or debris [2]. Infected branchial cleft lesions can have thickened cyst walls, internal echogenic foci, and associated reactive lymphadenopathy [Video 23.2] [1, 2].

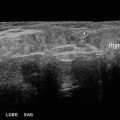

Fig. 23.4

The ultrasound appearance of a fluid-filled cyst with posterior enhancement

23.3 Neoplastic Lesions

Neoplastic lesions in the head and neck are more commonly seen in an adult population. Ultrasound can provide immediate information to the clinician about exact location and can narrow the differential diagnosis.

23.3.1 Benign Neoplastic Lesions

23.3.1.1 Lipoma

Lipomas in the head and neck are relatively common lesions and are typically easily diagnosed by clinical history and physical examination alone. Occasionally these can be located deeper within the neck, and ultrasound may be a useful adjunct in these cases. Lipomas are typically located superficially in the subcutaneous tissues, and their appearance can vary based on the amounts of fat and fibrous tissue that are present. Lipomas are well-circumscribed lesions that are ovoid and have a characteristic striated appearance [Fig. 23.5]. Some describe a hypoechoic appearance to lipomas , but they are more frequently isoechoic or hyperechoic [2, 10]. There is no to minimal internal blood flow seen, and liposarcoma should be considered lesions that appear to be lipomas with internal blood flow [10].

Fig. 23.5

A young man presented with a palpable soft right supraclavicular mass. Ultrasound demonstrated a 4.8 cm ovoid isoechoic heterogeneous mass with no vascularity, consistent with a lipoma

23.3.1.2 Paraganglioma

Paragangliomas in the head and neck are more typically evaluated with other imaging modalities, but ultrasound can be useful in establishing this as a diagnosis in a new patient with a neck mass. Ultrasound can also be used to monitor for recurrence of carotid body tumors. Paragangliomas are solid, hypoechoic masses that are highly vascular on Doppler imaging. Carotid body paragangliomas splay the internal and external carotid arteries. Due to overlying bony anatomy, glomus jugulare tumors cannot usually be evaluated with ultrasound [2, 10].

23.3.1.3 Schwannoma and Neurofibroma

Neurogenic tumors, including schwannomas and neurofibromas, are hypoechoic, often vascular masses that can sometimes be seen in continuity with a peripheral nerve on ultrasound exam [Figs. 23.6 and 23.7]. In those that can be visualized relative to their nerve of origin, the surgeon can see schwannomas based more marginally relative to the nerve [Video 23.3]. Neurofibromas, on the other hand, originate more centrally. These lesions are most often located in the posterior triangle of the neck and are fusiform with smooth margins [2, 10].

Fig. 23.6

This level III neck mass along the carotid sheath was proven to be a schwannoma along the vagus nerve

Fig. 23.7

In a patient with history of neurofibromatosis type 2, ultrasound demonstrated a large, lobulated, hypoechoic, vascular mass with a dumbbell appearance. The deep component is located within an enlarged vertebral foramen, consistent with a neurofibroma

23.3.1.4 Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are vascular lesions that are usually diagnosed early in life [Video 23.4]. Not surprisingly, they demonstrate vascularity on Doppler imaging [Fig. 23.8]. In lower-flow lesions, the power Doppler setting may be useful. When the vascular spaces are small, these lesions can be hyperechoic. Larger spaces are hypoechoic. The compressibility of the lesion as well as the vascularity can help distinguish this from other lesions, and sometimes a feeding vessel can be identified as well [2, 10]. Calcifications may also be present.

Fig. 23.8

Ultrasound imaging using color Doppler of a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome demonstrating flow within the lesion. Speckled calcification can also be visualized

23.3.1.5 Lymphangioma

Like hemangiomas, lymphangiomas are diagnosed early in life in most cases. Lymphangiomas will have a complex and multiloculated appearance and are compressible on ultrasound [Fig. 23.9]. Hyperechoic areas may also be seen and these are due to clustered lymphatic channels. The lack of vascularity on Doppler imaging helps to distinguish the lymphangioma from a hemangioma [2, 7, 10].

Fig. 23.9

Ultrasound of a soft, multiseptated, avascular, complex cystic lesion with internal debris next to the submandibular gland, in keeping with a lymphangioma

23.3.2 Malignant Neoplastic Lesions

23.3.2.1 Lymphoma

Lymphomatous lymph nodes can be difficult to distinguish sonographically from reactive lymph nodes and nodes in inflammatory diseases like sarcoidosis . They are hypoechoic in nature, rounded or oval in shape, and have smooth margins [Fig. 23.10]. Necrosis and extranodal extension are uncommon. Doppler imaging can show hilar vascularity, similar to reactive nodes, or a mix of hilar and peripheral vascularity [2, 11].

Fig. 23.10

A patient with a history of B-cell lymphoma in remission presented with a palpable right neck mass. Ultrasound shows an enlarged, homogeneous, hypoechoic adenopathy with loss of the fatty hilum in level III. Biopsy revealed lymphoma recurrence

23.3.2.2 Non-thyroid Metastatic Lesions

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common metastatic lesion found in the neck, but other metastatic lesions can be seen, especially in the supraclavicular region [2]. As with other entities mentioned above, ultrasound may not be the imaging modality of choice in staging and initial treatment due to its inability to image areas like the retropharyngeal lymph node basin. It does, however, offer a useful adjunct both in the initial diagnostic setting and for follow-up.

As in thyroid lymph node metastases, non-thyroid metastases have a rounded appearance with a loss of the fatty hilum. There is often a heterogeneous internal appearance due to necrosis. The border of involved nodes can be indistinct, and there can be evidence of invasion of adjacent structures. Doppler assessment can show a disorganized vascular pattern [2, 12, 13].

23.4 Reactive Lymph Nodes

The differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy is quite extensive. The ultrasonographer must be able to distinguish reactive or benign lymph nodes from those that are pathologic so the patient may avoid unnecessary invasive testing and distress. Fortunately, there are characteristic ultrasound features of benign and pathologic lymph nodes that can assist in making the diagnosis.

Reactive and normal lymph nodes, both benign, share many of the same ultrasound features. Pathologic lymph nodes tend to appear rounded, and reactive nodes are oval in shape [14]. The oval shape for reactive nodes is defined as a short axis/long axis ratio of <0.5 [15]. Benign lymph nodes are typically anechoic or hypoechoic. The most characteristic finding of benign or reactive lymph nodes is a bright fatty hilum containing a vascular strip. This finding has a 90 % accuracy in diagnosing a benign lymph node [16]. Benign lymph nodes typically maintain a sharp border, while malignant or otherwise pathologic nodes may infiltrate into surrounding structures [15].

The vascular flow pattern may also assist in determining the nature of the node. Peripheral vascularity is generally suggestive of a pathologic process [17]. With color flow Doppler, the hilum of a reactive or normal node demonstrates a vascular pattern, with the surrounding nodal structure relatively avascular [14, 17]. Reactive nodes will also lack many of the features characteristic of certain malignancies: heterogeneous echogenicity, calcifications , cystic spaces, or intranodal necrosis [16].

23.5 Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease process whose etiology is not definitively known. A systemic inflammatory response, perhaps a reaction to an as-of-yet unknown antigen, results in the formation of noncaseating granulomas, usually involving the hilar mediastinal lymph nodes. The diagnosis must be made by histopathologic analysis of tissue specimens. Most patients present with pulmonary symptoms; however, the head and neck soft tissues are affected in 10–15 % of cases, with approximately 50 % of these patients displaying cervical lymphadenopathy [18].

Sonographic features of sarcoidosis within the cervical nodes and salivary glands are relatively nonspecific, and definitive diagnosis is made with tissue analysis. Lymph nodes involved with sarcoidosis are hypoechoic and lose the vascular hilum. They are frequently large and palpable. The lateral, supraclavicular, and posterior neck compartments are typically involved, and findings may be bilateral and asymmetric. Cervical nodes in sarcoidosis usually occur in a cluster and display a rounded shape, rather than the typical ovoid shape of benign reactive lymph nodes [Fig. 23.11] [19]. These nodes do not display extracapsular extension or infiltrate into surrounding tissues. Large nodes are hypoechoic/anechoic and may display a “punctate echo structure” with small hyperechoic areas within the node [20].

Fig. 23.11

A patient with history of sarcoidosis presented with bilateral enlarged, asymmetric cervical/supraclavicular suspicious lymph nodes, which were hypoechoic with a loss of the fatty hilum. Biopsy was consistent with sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis also may involve the salivary glands. Ultrasound of these areas in sarcoidosis patients may demonstrate intraparotid nodal enlargement, as well as variable echogenicity and mixed involvement of the gland [21, 22]. The parenchyma of the gland may appear heterogeneous and may display multiple septae. Small hypoechoic nodules may be present throughout the parenchyma. Upon color flow Doppler imaging of these hypoechoic areas, they may appear hypervascular [21].

Heerfordt syndrome , the classic presentation of parotitis, facial nerve paralysis, and uveitis caused by sarcoidosis, is a rare entity, occurring in 6 % or less of patients with the disease [23]. With this syndrome, ultrasound may reveal diffuse enlargement of the parotid glands with multiple hypoechogenic nodules. These hypoechoic areas correlate clinically with granuloma formation within the glands [20]. Duplex ultrasound of the involved parotid demonstrates hypervascularity [24].

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of mediastinal nodes in sarcoidosis has been described as a useful method of diagnosis, with a diagnostic yield >93 % [25, 26]. Tissue specimens display the characteristic noncaseating epithelioid cell granuloma. Within the neck, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy has been reported for sarcoidosis involving supraclavicular nodes [27], but there is limited evidence of its use within the neck for the indication of sarcoidosis .

23.6 Ranula

Ranula is a mucocele formed by the obstruction of the sublingual ducts and a subsequent collection of salivary fluid. Physical exam of the patient may reveal a soft fullness in the floor of mouth or a neck mass. Many individuals presenting with a ranula are young adults or pediatric patients, and consequently radiation-free ultrasound is an ideal method for initial assessment and diagnosis. Treatment is surgical and involves removal of the ranula with removal of the offending sublingual gland and/or marsupialization.

Ultrasound findings of the ranula are characteristic. Findings include a homogeneous, hypoechoic, compressible, unilocular cyst with well-defined borders and a thin cyst wall [28, 29]. The sublingual gland and mylohyoid muscle are visualized adjacent to the lesion. Occasionally there may be protinaceous intralesional debris. A “plunging ranula” is defined by the cystic lesion descending beyond the posterior aspect of the mylohyoid muscle and into the neck into the submandibular space, resulting in the presence of a soft, nontender, neck mass. The mylohyoid defect through which the ranula descends may be visualized with high-resolution ultrasound [29]. Ultrasound has been advocated for monitoring these patients for recurrence postoperatively as a noninvasive, low-cost, and radiation-free imaging modality [28].

23.7 Laryngocele

Laryngoceles are rare air-filled laryngeal lesions that form as an acquired dilation of the laryngeal ventricle and communicate with the lumen. These dilations typically form from increased glottic pressure and may be bilateral. Laryngeal tumors potentially causing supraglottic obstruction should be ruled out. Laryngoceles may be internal or external (also called a combined laryngocele), as defined by whether or not they herniate through the thyrohyoid membrane. External laryngoceles may present as a soft, compressible neck mass. Mucous or serous material may fill the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree