Fig. 42.1

A dual-probe handheld ultrasound unit is used in the linear, nonvascular setting to visualize a young woman’s thyroid in a primary care clinic. GE V-Scan used with permission of GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA

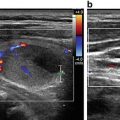

Fig. 42.2

A basic point-of-care ultrasound machine is used by an Emergency Medicine resident to practice thyroid ultrasound during ultrasound rounds. (a) SonoSite M-turbo; (b) X-porte; and (c) EDGE. Used with permission of SonoSite, Bothell, WA, USA

Point-of-care ultrasound of the thyroid is typically utilized to answer a specific set of questions at the bedside. Most practitioners who are performing POCUS of the thyroid have imposed time constraints that prohibit the acquisition and interpretation of a comprehensive thyroid ultrasound that is typically obtained in radiology or thyroid centers. When focused, point-of-care thyroid ultrasounds are being performed at the bedside, the clinician is usually interested in answering the following questions:

- 1.

Does the patient have an enlarged thyroid gland?

- 2.

Does the patient have a focal or discrete thyroid mass?

- 3.

Does the patient’s ultrasound demonstrate findings suggestive of thyroiditis?

- 4.

Does the patient have a goiter?

Clinicians who are performing these point-of-care ultrasound examinations of the thyroid have been trained to obtain useful sonographic information at the bedside that can be used to help tailor future treatment, management, and follow-up options for the patient.

42.4 Technique

As with other point-of-care ultrasound examinations, clinicians in the primary care and acute care settings are performing focused, goal-directed imaging of the target structures. During a point-of-care ultrasound of the thyroid, the patient is placed in a supine position with the neck in slight hyperextension. Using a high-frequency linear transducer, the clinician will typically start by obtaining an image of the trachea in the midline and note the right and left thyroid lobes adjacent to the thyroid. An image of the thyroid isthmus is typically recorded in this transverse plane. It is important to confirm that the orientation is in the conventional position: for transverse views (the patient’s right side is displayed on the left of the monitor as physician faces monitor); for longitudinal views, the superior thyroid pole is on monitor left. This is easiest to do with finger pressing one edge of the probe’s flat footprint to detect where the motion displays on the monitor; alternately the marker facing the patient’s right side can be helpful but this varies with machines and can change when machine settings are changed. The clinician will then scan through each thyroid lobe and the isthmus in both the longitudinal and transverse planes. During the scan, the clinician will sweep entirely through both glands and adjust the depth to ensure adequate imaging of posterior and far field structures.

Some clinicians practice a basic “eyeball” or global evaluation of the thyroid echotexture and size and will recommend referral for comprehensive imaging if any obvious abnormalities are noted. Others will perform a more comprehensive and detailed ultrasound evaluation of the thyroid gland at the bedside. Clinicians performing point-of-care ultrasound evaluations of the thyroid as a regular part of their practice will often seek to obtain transverse images of the superior, mid, and inferior portions of the right and left thyroid lobes. In addition, images will be recorded of the medial, mid, and lateral portions of both lobes in a longitudinal fashion. The size of each thyroid lobe is generally recorded in three dimensions: anteroposterior, transverse, and longitudinal, and color or power Doppler examination can also be used to supplement grayscale evaluation of any focal or diffuse abnormalities noted. It is often useful to extend the scan to include the soft tissue above the isthmus (e.g., to evaluate a possible pyramidal lobe congenital abnormalities such as a thyroglossal duct cyst, or if any superior palpable abnormality is noted.)

It is important to obtain both still images and to record short video clips for archiving, documentation and billing purposes. These still images and video clips should include standardized images of the entire thyroid gland in both longitudinal and transverse planes, and also recordings of any abnormalities noted in the gland and surrounding structures. Current research is underway to delineate which abnormal sonographic findings are likely non-pathologic (i.e., nodules <1 cm with no findings associated with malignancy), in comparison to those that require urgent or expedited follow up with comprehensive thyroid imaging with dedicated specialists.

42.5 Thyroid Ultrasound in the Non-acute Care Setting

The thyroid examination is a classic component of the complete physical examination, and despite profound technological advancements and innumerable changes in medicine, it is still deemed important enough to be listed as #1 on the Stanford Medicine 25 [7]. However, when compared with postmortem thyroid weight and sonographically determined thyroid volume, palpation has been shown to be highly inaccurate for estimating thyroid size [8]. In surveys of medical students, interns, residents, and attending internists detecting a thyroid nodule had one of the lowest self-confidence scores of 15 key physical examination skills, along with one of the highest perceived utility scores [9].

Below are some cases encountered in the clinical setting where a portable thyroid ultrasound can be useful in the patient’s assessment and management .

42.5.1 Case 1: Why Is Her Heart Racing?

While on a medical service trip in extremely rural Haiti a 32-year-old woman presents with a chief complaint of heart racing. The only available diagnostic tools are your stethoscope and your portable ultrasound.

On examination her heart rate is about 110 beats per minute, she has an enlarged, smooth thyroid, and a very soft bruit. The rest of her exam is unremarkable. With handheld ultrasound you confirm thyromegaly (Fig. 42.3, Video 42.1). To further assess her tachycardia you perform focused cardiac ultrasound to rule out congenital or acquired heart disease, and assessed volume status via inferior vena cava ultrasound. These studies are unremarkable.

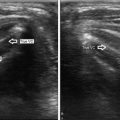

Fig. 42.3

An enlarged right lobe of the thyroid as captured on a handheld ultrasound unit. This measures 2.6 cm in depth as demonstrated by the yellow annotation

Your clinical diagnosis is Graves’ disease ; however, with no other diagnostic or treatment capabilities you are only able to advise travel to the nearest clinic which is 2h away, and some money, as they only perform basic testing and will likely have to refer her onward via ferry to Port-au-Prince, which you know she cannot afford.

Thyroid ultrasonography for goiter prevalence assessment in developing countries has been shown to be feasible [10], and has been used to assess iodine deficiency via World Health Organization recommended surveillance methods in rural/mountain areas as well [11]. This case demonstrates the utility of point-of-care ultrasound in resource-limited settings for detecting thyroid pathology in addition to simple screening/prevalence assessment purposes.

42.5.2 Case 2: Does She Have a Thyroid Nodule ?

A healthy 24-year-old medical student presents to your primary care clinic after learning the thyroid examination in her Endocrine clinical skills lab. She has been more anxious lately, always “runs hot,” and has self-diagnosed Irritable Bowel Syndrome, but thinks her bowel movements have been more loose lately. She is concerned she found a thyroid nodule on herself, though her clinical skills teacher on further examination did not appreciate this. However, she asserts that she does have some symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and worries she could have a “hot” nodule that her clinical skills teacher could not palpate.

You are up to date on clinical recommendations and well aware that the American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends formal thyroid sonography for all patients with known or suspected nodules, while at the same time acknowledging that high-resolution thyroid ultrasound is able to detect thyroid nodule in 19–67 % of individuals [12]. You recall your own erroneous self-diagnosis of hypothyroidism in the setting of fatigue from studying long hours and being persistently cold (while in Boston for the winter!). You ask yourself “Am I really going to order a formal ultrasound for a suspected thyroid nodule that the most respected clinician at the university could not palpate?” Thankfully, the answer is no, as you have been attending ultrasound training sessions for years and incorporated point-of-care ultrasound in your practice for reasons just like this, along with a plethora of other clinical indications. You are actually one of the proponents for point of care ultrasound incorporation into the medical school curriculum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree