© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017

Mira Milas, Susan J. Mandel and Jill E. Langer (eds.)Advanced Thyroid and Parathyroid Ultrasound10.1007/978-3-319-44100-9_4141. Ultrasound for Radiologists: What I Learned from Lifetime Practice

(1)

Department of Radiology, The Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Keywords

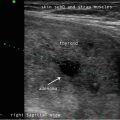

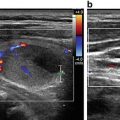

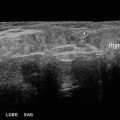

ThyroidCervical nodesRadiologyRadiologistUltrasoundSonographyThe rapid expansion of technology has caused most radiology practices to focus on the so-called “high-tech” diagnostic radiology exams , such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) , computed tomography (CT) , and positron emission tomography (PET) . There is likely a subconscious bias among most radiologists (and perhaps non-radiologists), that these complex and expensive exams with hundreds, and sometimes over a thousand images, displayed from multiple imaging planes with the aid of advanced reconstruction platforms, must always be superior for diagnosis as compared to the low-tech radiology exams. As a subspecialist radiologist in diagnostic and interventional sonography for the last 25 years, I can proclaim with pride that for imaging of the thyroid and cervical nodes , sonography completely outperforms all other exams. The superficial location of the majority of the structures in the neck affords an unhindered view with the ultrasound probe and the spatial resolution of sonography surpasses that of MR and CT, uniquely allowing the detection of subtle and critically important findings such as microcalcifications and infiltrative margins within thyroid nodules and tiny cystic regions in cervical nodes. The real time nature of sonography allows for dynamic assessment which can be useful for diagnosis but more importantly provides the safest and most efficient guidance for biopsies and other interventions in the neck. Sonography is unquestionably the most essential imaging tool for the care of patients with thyroid (and in many cases, parathyroid) disease. I must admit that it is a sort of a moral victory that my dedication to and passion for the practice of sonography is affirmed by the superiority of sonography in this clinical context.

The practice of sonography is incredibly appealing to me because the field ranges broadly across nearly all aspects of health care. This challenges me to be knowledgeable and current about so many different medical and surgical subspecialties in order to provide meaningful interpretation of the images, as well as being skillful in the performance of the exam and biopsy procedures. More importantly, the practice of sonography offers the ability to provide direct patient care. The sonography exam and the performance of an ultrasound-guided procedure are among the most intimate patient care experiences in the practice of radiology both from the patient perspective and (in my practice) from the physician perspective. It is a hands-on encounter with an opportunity for the radiologists to truly care for a patient, by listening to them, examining them and having dialogue about the findings, an experience quite similar to a typical physician office visit.

41.1 The Art of Sonography

Technologic advances in the last several years have allowed for the development of good quality, portable and inexpensive sonographic instruments that can be used in the office setting and in the operating room. This availability has motivated a variety of subspecialties that care for patients with thyroid and parathyroid abnormalities to encourage physicians and other care providers to learn to become adept at examining the neck with ultrasound and incorporate sonography as a routine part of their practice .

It is wonderful to witness the ever expanding role of sonography in the care of patients. The challenge is that, unlike CT and MR, the sonographic exam is not an automated process; it is an exam that needs to be created by the sonologist (noting that term sonologist refers to the person operating the ultrasound equipment without distinction by medical background or training) by using skillful manipulation of the probe and sonographic controls. The sonologist must pay incredible attention to small details while adhering to imaging protocols to be thorough, but must also be prepared appropriately to expand the exam to assure that they have fully investigated the entire neck when abnormalities are noted. Therefore, it remains essential that all sonologists recognize that, in order to provide optimal patient care, the exam needs to be both expertly performed and expertly interpreted. It is incumbent upon the sonologist to maintain a healthy respect for the challenges that the performance of high quality sonography presents and an appreciation that the recognition of incredible subtleties will dramatically alter the diagnosis. In the radiology practice model, the ultrasound lab is responsible for performing a complete and comprehensive diagnostic exam of the neck whereas in the non-radiology practice model it is acceptable to use sonography in a more limited capacity or so-called point-of care sonography. In most radiology practices in the USA, the images are typically acquired by ultrasound technologists (sonographers ), who are highly trained medical professionals who need to be certified and work within an institution accredited to perform sonography. It is the responsibility of the sonographers to take a brief patient history, to perform the real time exam, and capture the required images as stipulated by practice guidelines. The thoroughness with which the neck is interrogated, the number of captured images and the diagnostic quality of the captured images will vary greatly depending on the skill and experience of the sonographer . I have worked with a number of outstanding technologists who are not only extremely skilled at the technical aspect of their craft but who are dedicated and caring professionals. They have strived to become educated about both the imaging findings and the clinical presentations of the disease processes of their patients in an effort to provide optimal patient care. Their diagnostic excellence has indeed been essential in the care of many patients seen in our ultrasound lab and I am incredibly indebted to all of them. There are too many technologists that I would like to publically recognize to list all by name, but I would like to give special recognition to a few. Caren Levine, RDMS, assumed the role as our first lead technologist in our multidisciplinary thyroid clinic. Caren is the consummate perfectionist in her scanning, consistently providing images of the highest quality and often capturing the most subtle abnormalities that I am sure would go undetected under another’s watch. Her expertise and compassionate care have made her the most sought after technologist for our returning patients, many of whom will only schedule their appointment with the knowledge that Caren will be there to perform their scan. Christopher Iyoob, RDMS (our ultrasound supervisor) and Bonnie Brake, RDMS, RVT (our lead technologist for interventional ultrasound) have provided the leadership and mentorship necessary to make sure all of our technologists meet our lab’s high expectations for diagnostic quality .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree