Chapter 2 Ultrasound of Peripheral Nerves

Ultrasonography is a safe and commonly applied imaging technique for the study of soft tissues in the human body. Real-time feedback on anatomic images is the main strength of ultrasound imaging. Physically, ultrasound refers to mechanical vibrations in media with frequencies beyond the upper limit of normal human hearing (20 kHz). During ultrasonography ultrasonic waves with frequencies ranging from 1 to 20 MHz are applied to the skin by a probe that contains an electromechanical transducer. This transducer consists of piezoelectric crystals that characteristically operate both as a transmitter and a receiver. The transducer converts electrical signals into mechanical vibrations (ultrasonic waves) that are transmitted into the underlying tissues. A part of the ultrasonic wave is reflected at the boundaries of different tissues and subsequently received by the transducer again. As the average velocity of sound through various soft tissues is relatively constant (1540 m/s), further signal analysis can be based on the time interval between transmitting and receiving the signal by the transducer. Although many physicians still think that sonographic pictures are difficult to interpret, the image quality has improved considerably over the past decade. For neuromuscular ultrasound, technologic advances have even made it possible to depict small parts like peripheral nerves with excellent resolution, commonly referred to as high-resolution ultrasonography. There is a growing interest in high-resolution ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for diseases of the peripheral nervous system, probably because of these new technologies. Over the past 15 years, the number of publications on this topic has rapidly increased. Until now, electrophysiologic studies have been the diagnostic mainstay in neuropathies. However, electrophysiologic studies may be falsely negative, equivocal, unreliable, painful, or technically difficult. Instead of testing function by means of electrodiagnostic studies (nerve conduction studies and electromyography), imaging studies provide different information on pathologic changes of the peripheral nervous system. Combining imaging and electrophysiologic studies could improve the diagnostic process and ultimately lead to the right treatment decisions. In this respect one could draw an analogy with imaging studies of the brain versus electroencephalography. Imaging studies may reveal pathologic changes of nerves and structural abnormalities that cause neuropathy (e.g., cysts, tumors, hematomas), and make it possible to study surrounding tissues (e.g., presence of synovitis in carpal tunnel syndrome).

Principles of Neuromuscular Ultrasonography

Physics

Ultrasonic waves in soft tissues are longitudinal waves that have several physical parameters: frequency (f, in Hz), wavelength (λ, in m), amplitude (u0, in m), and velocity (c, in m/s).1 The relationship between velocity, wavelength, and frequency is expressed by the formula: c = λf. Although the velocity of ultrasound is relatively constant in various soft tissues, it is principally dependent on the density (ρ, in kg/m3), stiffness (K, in kg m–1 s–2), and temperature of that particular tissue. Another important concept is the (acoustic) impedance (Z, in rayls or kg m–2 s–1), which is related to velocity and density as follows: Z = ρc.

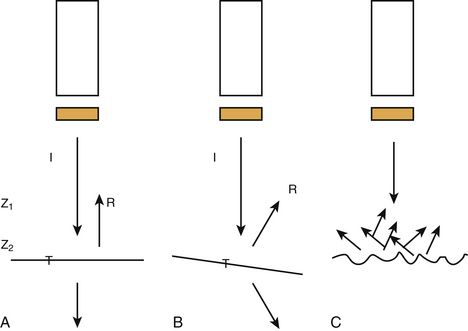

At the boundaries of two types of tissue (or media) a part of the ultrasound is transmitted and another part creates echoes by reflection (Fig. 2.1). These boundaries are called interfaces. The degree of reflection (or intensity reflection coefficient, R) at the interface depends on the impedances of the two media involved. When the ultrasound beam is perpendicular to a smooth interface, R = (Z2 – Z1)2 / (Z1 + Z2)2, where Z1 is the impedance of medium 1 and Z2 the impedance of medium 2 (see Fig. 2.1A). Therefore, the greater the difference in impedance between two media, the more reflection (or echo) occurs. When the ultrasound beam is not perpendicular to the interface, R and the intensity of the transmitted (refracted) beam are also dependent on the angle of insonation (see Fig. 2.1B). The angle of insonation is measured perpendicular to the interface. The energy is reflected in different directions (scattering) when the ultrasound beam hits a rough surface or small particles (see Fig. 2.1C). During its passage through the various tissues, part of the ultrasound energy is transformed into heat, a process called absorption. As a result of reflection, refraction, scattering, and absorption, the energy of the ultrasound beam is attenuated. Both scattering and absorption are dependent on the type of tissue and the insonation frequency: the higher the frequency the more scattering and absorption. High-frequency ultrasound is therefore less capable of penetrating more deeply located tissues. Reflections from deeper tissues are weaker than those of more superficial structures, and therefore these are usually amplified by time gain compensation.

Transducers

Dependent on the application, one may choose different types of transducers. So-called linear array transducers are used for nerve imaging. These transducers are composed of a row of many single transducers (piezoelectric chemical or crystal elements). The vertical picture lines on the monitor are formed by successive activation of these crystals (the ultrasound beam runs along the array). In modern transducers, a group of neighboring crystals create a single beam that runs along the array by repeatedly moving the group, one element at the time. Transducers produce ultrasound in pulses. These pulses are waveforms with a certain length and can be anatomized into several sinusoidal waves of different frequencies (Fourier analysis). The spectrum of frequencies of these sinusoidal waves is called bandwidth. As the pulse length decreases, the bandwidth increases. Bandwidth and central frequency are both used when referring to the frequency of a transducer. The rate at which the vertical scan lines are activated again is dependent on the pulse repetition frequency (PRF) and the number of scan lines as follows: scan or frame rate equals PRF divided by the number of scan lines. The shape of the ultrasound beam produced by the transducer is like that of an hourglass. The neck represents the focal zone, and there the intensity of the beam is at its maximum. This narrowing of the ultrasound beam is achieved by focusing.

Resolution

The ultimate image quality is dependent on spatial and contrast resolution. Contrast or tissue resolution is defined as the ability to distinguish between different normal tissues and normal from abnormal tissues, whereas spatial resolution refers to the ability to depict and distinguish small objects that are in close proximity.2 Spatial resolution can be further divided into axial and lateral resolution. Axial resolution is defined as the ability to separate two objects lying in tandem along the axis of the ultrasound beam. The axial resolution is improved when the pulse length decreases (bandwidth increases) and the insonation frequency increases. The lateral resolution is improved by using a smaller beam width at the focus zone, or by reduction of the frame rate, but also by the technique of successive grouping of crystals as described above. Resolution can be further increased by using multiple rows of crystals.

Artifacts

As a result of the properties of ultrasound, there are several possible artifacts.1,3–5 One should recognize such artifacts because they are potentially misleading. Several artifacts may also degrade the image quality.

Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques

Image quality has been significantly improved by the increase in computational power, allowing the use of more sophisticated automated analysis algorithms that are essential in working toward the reproducibility necessary for functional imaging. One of the biggest advances in image quality over the past 15 years has been the advent of tissue harmonic imaging, where the imaging of the second harmonic returned from tissue helps remove much of the clutter from ultrasound images. Increased computer power has also allowed the implementation of real-time image enhancement features such as spatial compounding (SonoCT Philips, Andover, Massachusetts), which significantly reduces the speckle inherent in ultrasound imaging, and postprocessing algorithms, which help to clearly delineate the features in an image (XRES Philips, Andover, Massachusetts).6

Harmonic Imaging

By generating the image from the second harmonic frequencies returning to the probe instead of the original insonating frequency, the quality of the image improves. Because the harmonic frequencies are generated at a deeper level than the surface, clutter, caused by tissue inhomogeneities, is reduced.7

Compound Imaging

In real-time spatial compound imaging the ultrasound is created by repeated, overlapping sequences of frames of different predetermined view angles. This technique improves image quality because scanning from different angles reduces acoustic artifacts (e.g., speckle and clutter). The artifacts are suppressed because these patterns are random (not correlated to each other) and averaged during the repeated sequences of scanning. Multiangle scanning is of benefit during musculoskeletal ultrasonography because anisotropy is reduced and small abnormalities can be better visualized.7,8 A disadvantage of increasing the frame rate is the greater risk of blurring when the transducer is moved too swiftly. Lin and associates systematically examined the image quality of real-time spatial compound ultrasonography as compared with conventional ultrasonography by means of a blinded review of 118 musculoskeletal images by three experienced ultrasonographers using a five-point rating scale. These investigators found that real-time spatial compound ultrasonography significantly improved the image quality (better definition of soft-tissue planes, reduced speckle and other noise, and improved image detail).9

XRES

XRES is an image-processing technique that performs real-time analysis of patterns at the pixel level. It looks at the predominated patterns within groups of pixels and brings them into order. It thereby reduces artifacts and brings margins and borders into greater definition.10

Extended Field-of-View Ultrasound

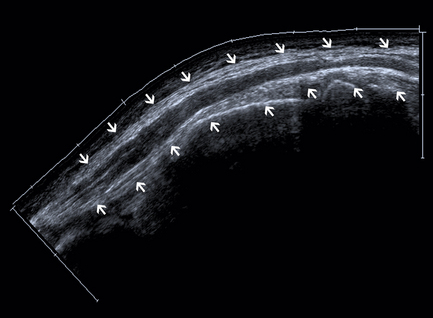

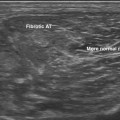

A drawback of using high-insonation frequencies and small (transducer) footprints is the small field of view. A small field of view often makes it difficult or impossible to identify and incorporate landmarks in an image, which are necessary for the orientation of the ultrasound. However, correlating scan frames while moving the transducer will extend the field of view. This technique makes it possible to line up a few consecutive single frames to create a panoramic picture (Fig. 2.2). There are two possible artifacts with the extended field-of-view technique: (1) scanning moving structures may result in distortion, and (2) when the area of interest includes an echo-free area, a skyward deviation of the image may occur because there are no echoes to correlate with when the transducer is moved.11

Three-Dimensional Imaging

Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasonography is rapidly gaining popularity as it moves out of the research environment and into the clinical setting, mainly in imaging of breast and abdominal lesions. This modality offers several distinct advantages over conventional ultrasound, including 3D image reconstruction with a single pass of the ultrasound beam; virtually unlimited viewing perspectives; accurate assessment of long-term effects of treatment; and more accurate, repeatable evaluation of anatomic structures and disease entities. However, experience in 3D ultrasonography of peripheral nerves is limited at this time.12

High-Resolution Ultrasound of Peripheral Nerves

Why Is Ultrasonography Suitable for Imaging of Peripheral Nerves?

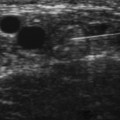

As a result of the new developments, as described earlier, the resolution of ultrasonography has considerably improved and is even better than that of standard MRI. As many peripheral nerves run a superficial course, they are easily accessible to ultrasonography. Even very small nerves and the fascicular pattern can be studied. The most important artifact during ultrasonography of the peripheral nervous system is anisotropy, which implies that the ultrasonographer must constantly guide the probe to obtain optimum visualization of the nerve. Because of the previously mentioned physical aspects, deeper-lying nerves are more difficult to study. The oblique course of peripheral nerves poses no problems to ultrasonography because the transducer can be moved along the course of the nerve, and extended field-of-view techniques may help create images of peripheral nerves in a longitudinal section over a long segment. This task is hard to accomplish with MRI. Although hyperintensity of nerves on short tau inversion recovery or fat-saturated T2-weighted fast-spin-echo images may indicate disease, this feature is of questionable value because it may also occur as an artifact caused by the magic angle effect.13 The echogenicity of a nerve may also be assessed as a marker for disease (e.g., hypoechogenicity may indicate increased water content).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree