Upper Airway Obstruction

Ramesh S. Iyer, MD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Distinguish the normal “shouldering” of the subglottic airway on an anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph from the tapered narrowing (“steeple sign”) seen in croup.

2. Recognize radiographic signs of epiglottitis, including the “thumb sign” and thickening of the aryepiglottic folds.

3. Identify pathologic prevertebral thickening on a lateral neck radiograph.

4. Recognize “pseudothickening” of prevertebral soft tissues on radiography.

5. Identify enlarged adenoids on lateral neck radiographs.

INTRODUCTION

Upper airway obstruction in children may be divided into acute and chronic etiologies. With acute obstruction, primary considerations include infection and foreign body aspiration. Chronic obstruction is typically associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Upper airway obstruction may also be divided by its location with respect to the vocal folds into supraglottic (epiglottitis), glottic, and subglottic (croup, retropharyngeal abscess) pathology.

Upper airway obstruction often causes inspiratory stridor, with expiratory stridor an ominous sign for worsening or severe obstruction. By contrast, expiratory wheezing is attributed to lower airway obstruction.1

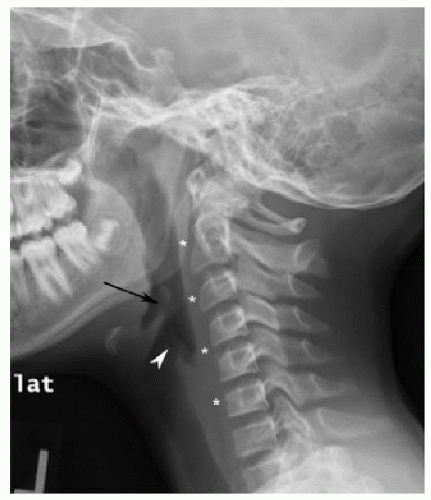

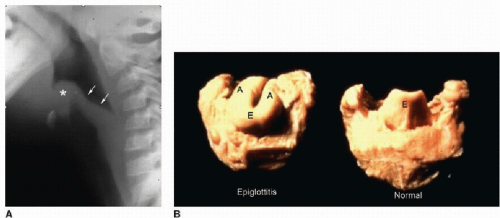

Imaging evaluation for both acute and chronic obstruction begins with AP and lateral neck and chest radiographs. Fluoroscopy and CT are useful adjunct modalities for disease characterization. On a well-positioned lateral neck radiograph, the epiglottis is a thin finger-like projection directed superiorly and posteriorly (Fig. 1.1). The aryepiglottic mucosal folds extend from the epiglottis anterosuperiorly to the arytenoid cartilage posteroinferiorly. These folds are normally thin and convex inferiorly. In general, prevertebral soft tissues should be less thick than the adjacent vertebral body below C3. From C3 and higher, soft tissues are normally less than half as thick as the vertebral body. Numerically, allowing for variations in patient age, prevertebral soft tissues should measure less than 8 mm at C2 and 14 mm at C6.2 The difference in thickness is attributable to the upper esophagus contributing to soft tissue thickness anterior to the mid and lower cervical spine.

CROUP

Croup, or acute viral laryngotracheobronchitis, is the most common cause of acute upper airway obstruction in children aged 6 months through 4 years, with a peak age of 1 to 2 years. The most frequent pathogen is parainfluenza type 1, with other viral agents including parainfluenza types 2 and 3, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, adenovirus, and rhinovirus. Incidence of croup is highest in the early fall and winter, but cases may occur sporadically throughout the year. These children present with stridor, a barking or seal-like cough, and hoarseness.3,4

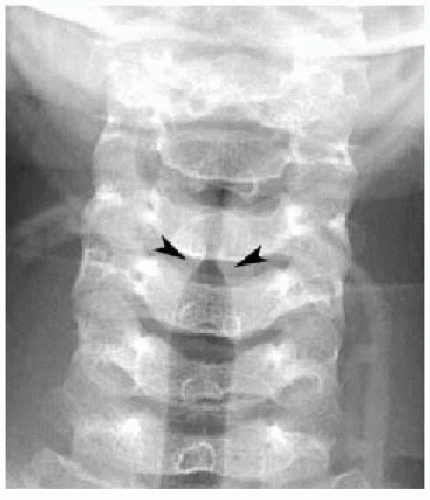

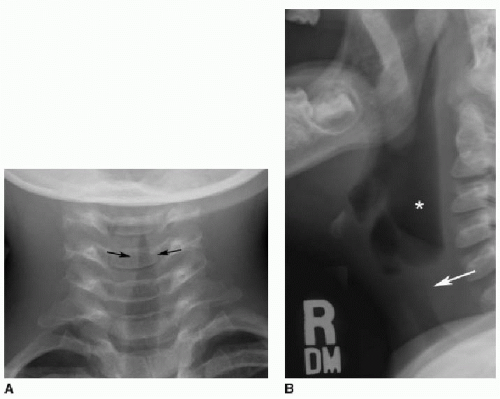

While the diagnosis of croup is most often a clinical one, frontal and lateral radiographs are often obtained to exclude more serious pathology. On a normal AP radiograph of the airway, the lateral walls of the subglottic larynx are convex outward, or “shouldered” (Fig. 1.2). In the setting of croup, mucosal edema causes tapered, symmetric narrowing of the airway at this level with loss of normal shouldering (Figs. 1.3A and 1.4). This appearance has been likened to a steeple, pencil tip, or inverted V. This narrowing may extend 5 to 10 mm below the vocal cords. This “steeple sign” is variably present in croup and is less commonly seen in epiglottitis. On a lateral radiograph, the subglottic airway appears indistinct or hazy, and the hypopharynx may be overdistended (Fig. 1.3B).3, 4, 5 and 6

Croup is typically self-limited and requires supportive care only. Nebulized epinephrine is effective in reducing subglottic edema through vasoconstriction.4,7,8 Corticosteroid use has long been debated, but recent studies have shown treatment benefits.3,9 Less than 10% of these children require hospitalization.4,10,11

EPIGLOTTITIS

Bacterial epiglottitis is a rare but potentially life-threatening cause of upper airway obstruction. The condition is characterized by acute inflammatory edema of the supraglottic airway including both the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds. In the past, most cases of epiglottitis were caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB). Since the widespread introduction of the HIB vaccine in 1990, the incidence has dropped substantially. The condition is now more common overall in adults than children, with other causative agents including Streptococcus, Staphylococcus,

Pseudomonas, and viruses. While it was previously most common in children aged 3 to 6 years, the mean age in children has shifted to about 15 years.3,12, 13 and 14 Characteristic clinical features include high fever, sore throat, hoarseness, drooling, and dysphagia.3,15

Pseudomonas, and viruses. While it was previously most common in children aged 3 to 6 years, the mean age in children has shifted to about 15 years.3,12, 13 and 14 Characteristic clinical features include high fever, sore throat, hoarseness, drooling, and dysphagia.3,15

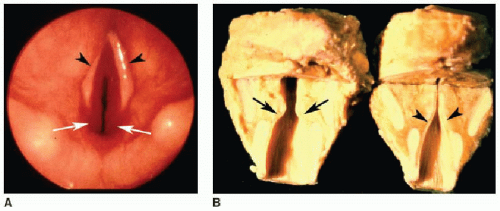

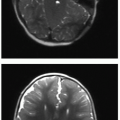

Radiography is performed for initial diagnosis, followed by direct laryngoscopy for confirmation. On a lateral neck radiograph, the epiglottitis is irregularly enlarged secondary to edema, described as the “thumb sign” (Fig. 1.5). The aryepiglottic folds are also enlarged and bowed superiorly. Confluent engorgement of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds obstructs the airway in epiglottitis. Associated findings include ballooning of the hypopharynx, loss of normal cervical lordosis, and occasionally narrowing of the subglottic trachea as noted in croup.16, 17, 18 and 19

One potential pitfall of diagnosing epiglottitis on lateral radiography is the reported “omega sign.” This sign describes the appearance of the normal epiglottis if imaged obliquely: curved prominent lateral folds project next to each other, producing an “omega” configuration and mimicking edema (Fig. 1.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree