CHAPTER 22 Upper gastrointestinal and colorectal stenting

PART 1 UPPER GI TRACT STENTING

Background

Less than 10% of patients with gastro-esophageal cancer survive 5 years (Lee, 2001). Oral intake of nutrition is vital in maintaining quality of life for these patients, particularly when considered by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) to be suitable for palliative treatment only. The development of significant dysphagia to solids and, more particularly, liquids as a result of occlusive neoplastic stricturing requires palliation that is effective and minimally invasive (Box 22.1). In this section, it is intended to review upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract stenting.

History

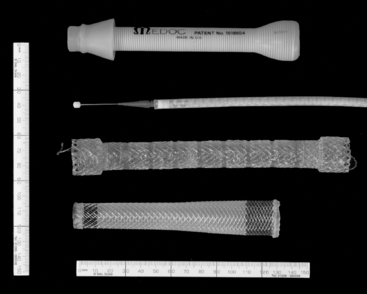

Historically, palliation of dysphagia resulting from occlusive malignancy has required surgical intervention. Celestin (1959) described a traction technique that required endoscopic guidance of an introducer and a mini laparotomy to gain entry high in the stomach; this enabled the tube (Figure 22.1) to be pulled through. Subsequently, the Nottingham introducer precluded the requirement for a laparotomy.

These intubation procedures took less than an hour to perform but required a general anesthetic and hospitalization of between three and ten days (Celestin, 1959; Davis, 1972; Bancewicz, 1979; Unruh and Pagliero, 1985; Kratz et al., 1989; Dunn and Rawlinson, 1992).

Self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) structure

The vast majority of upper GI SEMS insertions are associated with neoplastic occlusion or tracheo-esophageal fistula. SEMS have also been used for benign conditions, such as achalasia, where other management options, such as myotomy, balloon dilatation or the injection of botulinum toxin, have failed. In a number of papers, the use of stents is not recommended for benign strictures (De Palma et al., 2001). Ackroyd (2001) suggests that SEMS should be used for benign strictures with caution as they can make matters worse, potentially making a stricture inoperable. The indications for upper GI SEMS insertion are given in Box 22.2.

Removable SEMS

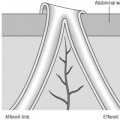

If a temporary stent is being considered, subsequent removal is undertaken endoscopically (Nam et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2008). Removable stents have a lasso woven into their proximal end. Under endoscopic control, forceps are used to grasp the lasso, tension will draw the proximal end of the stent closed and away from the esophageal wall. Maintaining hold of the lasso, the scope and forceps are then drawn out together with the stent.

Approaches to esophageal and gastro-esophageal SEMS insertion

SEMS provide a significant benefit in palliating malignant dysphagia, but there is broad discussion as to the best method to employ for their insertion. The literature suggests a bias towards a joint endoscopic/fluoroscopic approach to SEMS insertion. Ramirez et al. (1997) reported that 83% of those members of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) who responded to a survey used a combined endoscopic/fluoroscopic approach for the deployment of SEMS. Described by Sarper et al. (2003) and others, the joint approach uses endoscopy to pass the guide wire across the stricture, the subsequent stent deployment being undertaken using fluoroscopic guidance. Singhvi et al. (2000) suggest fluoroscopy is not necessary, advocating the use of a thin gastroscope, possibly in conjunction with a dilator such as the Savrey buginage, to assist with tight strictures. The routine use of general anesthetic for endoscopic SEMS insertion has also been reported (Singhvi et al., 2000; Sarper et al., 2003; Sabharwal et al., 2003; Soussan et al., 2005a, 2005b). The literature, however, also supports the use of fluoroscopy alone for deployment (Laasch et al., 2002; Saranovic et al., 2005; Law, 2008). The technical and clinical success rates for the deployment of esophageal SEMS are reported as similar whether using an endoscopic/fluoroscopic technique or fluoroscopic alone (Petruzziello and Costamagna, 2002).

Some units use endoscopy alone for the insertion of SEMS, but the advantages of this approach are limited. It can be used where there is limited access to fluoroscopy (Rathore et al., 2006). Singhvi et al. (2000) report using endoscopy alone as being a quick procedure (15 minutes) and resorting to the use of fluoroscopy is not routinely needed.

Fluoroscopically guided SEMS insertion: technique

Fine bore intubation is a natural skill progression for GI radiographers or radiologic technologists experienced in demonstrating esophageal pathology. (The techniques and benefits of technician performed fine bore intubation are described as a service development in Chapter 11.) In performing complicated fluoroscopically guided naso/orogastric intubation, GI radiographers and radiologic technologists are ideally placed to be involved in a joint approach with a clinician (gastroenterologist, surgeon or radiologist) in performing the first part of SEMS deployment by transgressing the esophageal lumen strictured by tumor (Law, 2008). Suggested protocol inclusions prior to upper GI SEMS insertion are offered in Box 22.3.

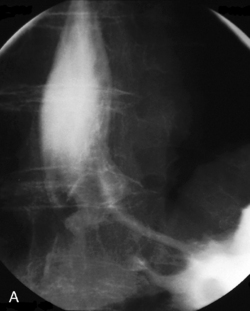

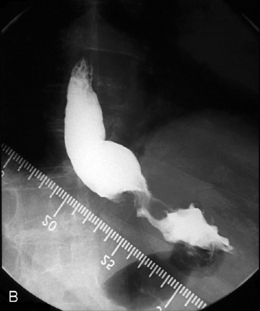

The barium swallow

Intubation across the stricture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree