(1)

Department of X-Ray and MRI, RailWay Clinical Hospital, Yaroslavl, Russia

Abstract

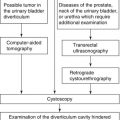

Urethral diverticula (UTHD) may be found in both women and men. Their course and diagnostics depend on anatomic peculiarities of the male and female urethra (Figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

Urethral diverticula (UTHD) may be found in both women and men. Their course and diagnostics depend on anatomic peculiarities of the male and female urethra (Figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

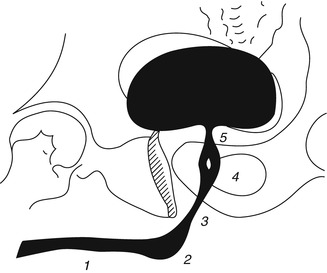

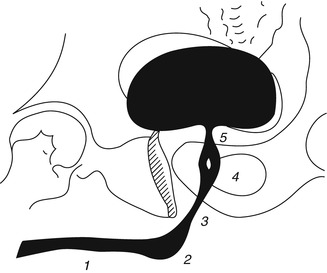

Fig. 4.1

Schematic urethrogram of a male. 1 pars pendula urethrae (cavernosa), 2 pars bulbosa, 3 pars membranacea, 4 pars prostatica (seminal hillock in the center), 5 neck of the urinary bladder (After Pytel and Pytel [1])

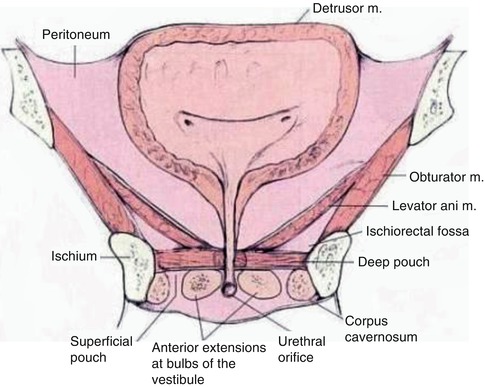

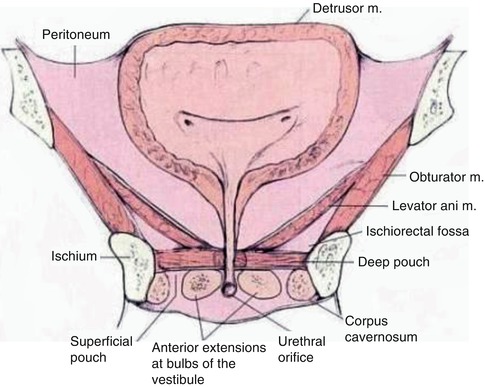

Fig. 4.2

Female urinary bladder and urethra (a schematic drawing). Front view (section). The triangle area between ureteral entrances and the inner urethral orifice is called genitourinary region (trigonum vesicae)

Urethra is part of the female urinary system and male urinary and genital system. The male urethra is 20 cm long and runs through both the pelvis and the penis and opens outward on its head. It has the following anatomical parts: (1) external orifice, (2) navicula, (3) penile part, (4) bulbous part, (5) membranous part, and (6) prostatic (proximal and distal parts).

The male urethra forms two curves: The first one with the curve pointing downward surrounds the pubic symphysis (curvatura subpubica) and the second one with the curve pointing upward is directed toward the root of the penis (curvatura praepubica). When seen in a urethrogram, the urethra has regular and smooth outline and has a shape of a bent strip of uneven diameter. The external sphincter of the urinary bladder divides the male urethra into two parts—the front and the rear part—each of them being divided into two parts in its turn. The front part of the urethra consists of the penile part (which runs through the penis) and bulbous part (expanded to the bulb shape), while the rear part includes the membranous part (perforating membrana urogenitalis) and prostatic part (surrounded by the prostate).

The female urethra is much shorter (3.0–4.0 cm) and a little wider than the male urethra, and in the urethrogram, it looks like a wide and short stripe with a regular outline. The urethra starts at the urinary bladder as an inner orifice for urine discharge, and then it runs through the urogenital diaphragm and opens as an external orifice near the pronaus in the depth of the interlabial space.

4.1 Ray Diagnostics

4.1.1 X-Ray Anatomy of the Urethra

In case of a conventional X-ray examination, images of the front and rear parts of the male urethra can be obtained only if two methods of introducing the contrast medium (XRCM) into the urethra lumen are combined. If the ascending or retrograde injection of XRCM is applied, the front urethra can be seen well in retrograde urethrograms. When the urinary bladder is filled with the contrast medium in the descending direction for excretory urography or when XRCM is injected in a retrograde or antegrade way into the urinary bladder, it is possible to see image of the rear urethra in the descending urethrogram during urination.

In a retrograde urethrogram, a normal front urethra of an adult male starting from the navicula and along the whole cavernous part can be traced as a strip with even parallel edges 1.0–1.5 cm wide. Bulbous urethra expands at the bottom wall and forms a curve pointing downward.

The rear urethra length is 3–4 cm. Its lumen above the external sphincter is tapered. Moderate narrowing around the cone edges is created by bulbocavernous muscles. When these muscles contract, the front and the sidewalls of this part of the urethra are depressed which may be mistaken for a stricture. The top of the tapered end of the front urethra passes into the rear urethra which upon retrograde XRCM introduction expands to a width of several millimeters and has a slight bent with incurvity in the front. The rear urethra forms a right or a little greater angle with the front urethra and extends as far as the bladder bottom.

The seminal hillock at the back wall of the prostatic urethra forms a spindle-shaped bulging. Location of the seminal hillock varies from the middle to the most distal part of the rear urethra. The upper and the lower poles of the seminal hillock pass into the urethral crest which is several millimeters wide and gradually flattens in the distal and proximal directions. The sides of the crest are supracollicularly formed by two shallow grooves which reach the neck of the bladder. Normally there is another shallow groove in the front wall of the urethra which extends from the urinary bladder to the level of the seminal hillock. All these grooves become invisible upon a significant expansion of the urethra lumen which takes place during urination.

If the urethra is unchanged, the prostatic and other paraurethral passages can be seen in retrograde urethrograms only under excessively strong pressure during XRCM introduction or through artificial blockade of the urinary bladder neck.

In case of voiding urethrography, the neck of the urinary bladder expands during urination and takes the form of a funnel. Rugae in the supracollicular part of the rear urethra disappear and its lumen becomes much larger (in an average up to 0.5 cm or more in the lateral projection on the level of the seminal hillock). Further, to the distal side from the external sphincter, the urethral lumen narrows.

During urination the rear urethra lowers due to lowering of the pelvic floor. This lowering is more prominent in the upper and rear parts of the pelvic floor which causes a displacement of the urinary bladder neck and of the upper part of the prostatic urethra downward and backward, and the rear urethra takes a more horizontal position. It must be kept in mind that the degree of the rear urethra repositioning depends also on the degree of the abdominal pressure increase during urination.

The female urethra is 3.0–4.0 cm long; the sphincter part takes two thirds of its length while one third is the intercavernous part. The sphincter part corresponds to the rear male urethra. In place of the male prostate, the female system contains a great number of paraurethral glands which are located mostly in the middle third of the urethra. Similar to the prostate glands, the female paraurethral glands are partly surrounded by nonstriated muscles. The external sphincter surrounds the urethra on the rear side in a horseshoe shape, merges with the retrourethral tissue (median lobe) and partly surrounds the vagina. The mucosa of both female and male urethras has longitudinal rugae which are well seen after moderate feeling of the urethra with a liquid XRCM.

UTHD, as all other diverticula, are divided into congenital and acquired ones.

Congenital UTHD are rare and have the form of saccular outpouchings of the rear wall connected by a narrow duct with the urethra, and like all other true diverticula, they comprise the same layers as the urethra.

Most often UTHD are localized in the front part of the urethra. The congenital UTHD diameter may be from 1 to 5–6 cm. These must be differentiated from the acquired UTHD which often appear after a trauma, including traumas of iatrogenic etiology, due to the development of the urethra stricture and presence of stones and foreign objects in it. In addition to that, the development of an acquired UTHD is related with paraurethral abscesses and festering cysts.

4.2 Female Urethra Diverticula

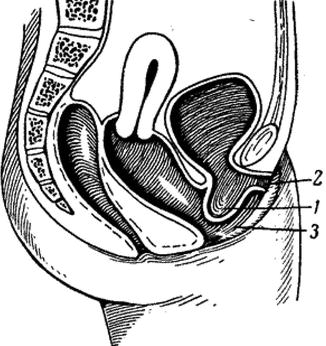

The urethral diverticulum is an outpouching of the rear wall which is connected with the urethral duct by means of a fistulous tract. This opening may vary in size and location; it may be located in any area between the external and internal urethral orifices; however, its most common location is the front part of the urethral duct (Figs. 4.1 and 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

Schematic drawing of the urethral diverticulum: 1 diverticulum, 2 external urethral orifice, 3 vaginal orifice (After Mazhbits [2]

4.2.1 Etiology, Localization, Pathogenesis, and Pathophysiology of UTHD

Based on literature evidence, paraurethral cysts and/or UTHD are found up to 1–6 % [2–6] more often in women at the age of 20 to 60 years. As noted by [7–14], although, based on the literature, UTHD frequency rate is 1–6 %, these data may be significantly lowered. According to Mazhbits [2], lately an increase of number of female patients with this disease is reported which may be related both with a greater number of patients who got inadequate treatment of sexually transmitted infections and with the widespread occurrence of various hygiene preparations based on soap. This causes obstruction of excretory ducts of paraurethral glands, development of inflammation, and, a as a result, development of a paraurethral cyst and/or UTHD.

As noted by [16–18], some authors consider UTHD a rare disease in female patients and classify it as anecdotal evidence. Other authors on the contrary report spreading of this disease and find it in 2–3 % women [19].

In the opinion of Pereverzev [18], UTHD is rarely found in women, and according to some authors, its frequency is 0.6–6 % among adults [1, 2]. Approximately the same statistics has been reported during the recent years, 1–5 % [3]. In accordance with this study which was carried out for 18 years and included investigation of the causes of recurrent infection in 863 women, true diverticula of the female urethra were found in 16 patients (2 %), ureterocele in 27 patients (3 %), and paraurethral cysts in 24 patients (3 %).

Existence of the female urethra diverticulum was described for the first time by W. Hey in 1805 [4]; however that nosologic unit was rarely defined until 1930 year, when occasional reports of this pathology started to appear. The general understanding and diagnostics of the disease have been improving since 1950 when urethrography with positive pressure was suggested. Thus H.J. Davis and K.W. Telinde published data on 121 female patient with UTHD which exceeded the number of such patients discovered for the preceding 60 years [22].

In 1970 an analysis of results of diagnostics and treatment of 120 UTHD in women was published which was carried out already in one clinic [23]. UTHD are found in women mostly at the age of 20–60 years (on average in 40-year-old patients), although it must be noted that they occur more often than they are diagnosed. If a histologic examination reveals unstriated muscles, it means that the UTHD has the congenital nature. However the majority of UTHD are acquired.

Numerous clinical observations confirm that UTHD are found at locations of paraurethral glands; however theories of UTHD pathogenesis have been actively debated for more than a century. Theories of UTHD formation are mostly focused on the following aspect: whether they are acquired or congenital. If UTHD are congenital, can they result from infections, childbearing, or even from iatrogeny? Proofs for the congenital nature of the disease lose their ground in view of the fact that UTHD are rarely found in girls. Thus during examination of 121 female patient which was carried out by the abovementioned authors [17], not a single case of the disease was diagnosed in patients under 20 years. Only 6.5 % of those patients developed symptoms before they reached the age of 20. Observations under analysis [17] confirm that the disease is congenital. The evidence is based on observations which revealed the location of diverticula in the area where atropic ureter is joining the urethra. Diverticula are located in the areas containing residual Gartner’s ducts, and some female patients were treated for UTHD containing cloacogenic rudiments.

At the same time there are judgments supporting the acquired UTHD genesis. At the beginning of the previous century, a birth trauma was considered to be the cause of their formation. From the pathogenetic point of view, it was explained as follows: The layer of the inner urethral muscles was ruptured under the pressure created by the fetus head or obstetric forceps which resulted in the formation of a hernia or a diverticulum. However further studies provided a reliable evidence that UTHD may occur in nonporous patients as well; thus based only on that fact, the hypothesis of the disease of acquired nature was rejected.

More acceptable are explanations stating that recurrent infections and obstruction of paraurethral glands cause development of suburethral cysts. These cysts may rupture spontaneously and break into the urethra lumen. Continuous irritation with urine which is retained in the cavity of this formation during each urination may finally result in epithelization and formation of a permanent diverticulum. Nowadays this explanation is accepted by majority of researchers who regard UTHD as an acquired disease of infectious etiology. There are reasons to believe that paraurethral glands get infected by the normal vaginal flora. The most often grown cultures are Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus faecalis. Nowadays it is believed that a urethral infection affecting paraurethral glands may cause formation of diverticula; however more often the leading role in the disease etiology is attributed to gonorrhea [18–21].

Many other possible UTHD causes were suggested: a birth trauma; high intravesical pressure during urination caused by closure and spasm of the external sphincter in neurologic patients, instrumental injuries, stones in a ureter, and also urethral strictures; and performance of urethral and vaginal surgeries which may be complicated with incomplete regeneration or a secondary infection. There are indications of a possible etiologic role of endometriosis, although among 46 observations of diverticula in the female urethra, only one case of endometriosis was reported [25]. Congenital factors may be present, including defects of Gartner’s ducts, a faulty union of primordial folds, the presence of cell rests, as well as wolffian ducts or vaginal cysts opening into the urethra. Experiments made by Hoffman [24] who got wax patterns of inflamed urethra revealed orifices of paraurethral glands in its lumen. These experiments confirm the concept of transformation of a suburethral infectious inflammation into abscess which is later covered with epithelium. Paraurethral glands get inflamed and block and later they break into the urethra creating linking channels between the diverticulum and the urethral lumen. According to microscopic studies, paraurethral glands can be found along the greatest part of the urethra (the rear and lateral location mostly), and most of them open in the distal part of the urethra. They represent a complicated system of tubuloalveolar structures and their number may be more than 30. Skene glands which are the largest of the paraurethral glands are emptied into the external orifice of the urethra and are often considered separately.

Paraurethral glands are tubuloalveolar structures which are mostly found in the distal two thirds of the urethra and open in the same area. In the macroscopic scale, paraurethral glands vary from simple saccular structures to complicated brachiferous structures. Their inflammation and disturbance of drainage into the urethra may also promote formation of diverticula in the distal part of the urethra. Sometimes the diverticula may have an extremely proximal location; in very rare cases they spread under the neck of the urinary bladder and the area of the vesical triangle [26].

Acquired UTHD develop from inflamed and blocked paraurethral glands which are usually found in the submucosal layer of the spongy tissue of the distal two thirds of the urethra. Cysts and abscesses gradually grow in size due to recurrent inflammations and obstructed ducts of paraurethral glands. Initially the growth results from displacement of the spongy vascular tissue and muscles of the urethra. The further growth weakens the urethra lining which leads to formation of a hernial bulging and detachment of two fascial layers of the urethropelvic ligament. In most cases, the diverticular sac expands to the back of the urethra which results in the development of a typical soft cystous formation on the front wall of the vagina. Not uncommon is the diverticulum expansion to the side which may be accompanied by a less prominent increase in volume and a greater detachment and separation of the vaginal and abdominal layers of urethropelvic ligaments. Less frequent is the diverticulum expansion to the front of the urethra, and still less frequent, it surrounds the urethra in the shape of a horseshoe. UTHD can be small and large, solitary and multiple, or multilocular. Finally the diverticulum contents break into the urethra lumen and a connection between the urethra and diverticulum appears. In some cases it breaks into the vagina causing formation of a urethrovaginal fistula. This concept is especially important for understanding surgical methods used for resection of the urethral diverticulum.

As noted by Pushkar and Anisimov [3], the term paraurethral cyst is not used in the overseas literature, and those conditions which are referred to and regarded as the paraurethral cyst in Russia are treated there only as a stage of UTHD pathogenesis.

4.2.2 Clinical Picture

About 20 % of UTHD are asymptomatic. In case clinical presentations are observed, the most typical complaint is urine dribbling after urination. There is a pictorial description which should be kept in mind during urethral diverticulum diagnostics, namely, three Ds: dysuria (disturbed urination), dribbling (intermittent flow of urine or dripping), and dyspareunia (sexual disorders) [3, 11–15]. This classical trilogy is typical for the urethral diverticulum. Sometimes urine has a putrefactive odor. Infection of UTHD causes painful urination (dysuria) and pains in the perineum and increase of the residual urine volume. Clinical symptoms in case of UTHD may vary from weak and occasional discomfort to strong pain and pronounced retention of urine in case of an acute infection. However in majority of patients, nonspecific irritative symptoms develop which are typical for the lower urinary tract in case of cystitis. Apart from the classical trilogy which is characteristic of UTHD, they may include the following symptoms: uroclepsia, hematuria, recurrent infections of the urinary tract, and urine retention. UTHD complications include stasis of urine and development of an infection in UTHD that creates ideal conditions for lithogenesis in some patients.

Mazhbits [2] suggested the following stages of UTHD course which lead to lithogenesis: (1) First is catarrhal diverticulitis which often proceeds without any clinical presentations. In such cases the cloudy urine which comes out of the diverticulum contains a small amount of epithelial cell and leucocytes. (2) Second is acute purulent diverticulitis with frank clinical presentations which is often complicated with inflammation of the rear urethra and the vesical triangle. Such a diverticulum has a swollen mucosa with a pronounced injection of blood vessels in some areas. The purulent contents consist of leucocytes, epithelial cells, erythrocytes, and a large number of bacteria. (3) Third is ulcerated diverticulitis, which often results in perforation due to destruction and thinning if the urethral wall tissue (G. Z. Gorovits). (4) Fourth is urethral diverticulum containing a single or multiple stones. This kind of diverticulitis could be described as calculous. The author described resection of the UTHD from which a stone was removed, 2 × 3 cm, with rough surface and hard texture, which caused insupportable pain during and after urination. He also provided observations by Mazhbits [2], who had described an extremely rare observation of the urethral diverticulum that contained 24 small faceted stones of various sizes in its cavity. Analysis revealed that they consisted of a mixture of phosphates, triple phosphates, and magnesium with a small amount of urates and carbonates. Organic matrix consists of protein. D. N. Atabekov diagnosed stones in diverticula in 2 of 13 patients. Stones were discovered in 7 out of 17 patients with diverticula operated by A. M. Mazhbits. A key sign of UTHD can be the presence of recurrent urinary tract infections in the anamnesis which were resistant to antibacterial therapy. A number of other symptoms (namely, presence of a tumorlike formation in the vagina, discharge from the urethra, painful ambulation) depend on localization of the diverticulum orifice. Urine retention, which occurs rarely, usually results from the presence of large proximal diverticula that obstruct and block the urinary bladder neck. These diverticula develop due to narrowing after recurrent infections. There are rare reports of formation of stones in diverticular cavity, including giant stones [12, 34]. Usually none of the symptoms described is proportionate to the diverticulum size. Thus large diverticula are often not sensed by patients, while small UTHD in case of an active infection may have very strong symptoms. Chronical complaints do not bear a uniform character; long periods of spontaneous remission are not uncommon. In addition to that, a carcinoma of the urethra may be defined in the diverticulum [6–10].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree