(1)

Department of X-Ray and MRI, RailWay Clinical Hospital, Yaroslavl, Russia

Abstract

Urinary bladder diverticulum (UBD) is an outpouching of the bladder wall creating an additional cavity which is connected by means of a more or less narrow neck with the urinary bladder cavity. The first UBD description and proposed tactics of its treatment is by Morganini and dates back to 1769 [1].

Urinary bladder diverticulum (UBD) is an outpouching of the bladder wall creating an additional cavity which is connected by means of a more or less narrow neck with the urinary bladder cavity. The first UBD description and proposed tactics of its treatment is by Morganini and dates back to 1769 [1].

There are true or congenital UBD and false or acquired UBD. True diverticula are usually singular and false ones are multiple. The congenital diverticulum is connected with the urinary bladder cavity by a narrow duct; its wall consists of the same layers as the urinary bladder wall. Urinary bladder diverticula are located most often in the area of ureteral orifices and bladder sidewalls; in rare cases they appear on the bladder top or around its bottom. Often the congenital diverticulum is larger and has a bigger capacity than the urinary bladder. It must be differentiated from such a rare congenital abnormality as the duplicated urinary bladder [2–5].

Several types of the congenital UBD are defined:

(a)

Complete duplication of the urinary bladder (synonym: duplicated urinary bladder)—two urethras present. Each of the two bladders has one ureter and is located in the pelvis. Duplicated urinary bladder is often combined with duplication of the colon and rectovaginal fistulas [6].

(b)

Incomplete duplication of the urinary bladder—the two bladders have a common neck and urethra.

(c)

Complete sagittal or transverse septum of the urinary bladder (synonym: two-chamber urinary bladder)—duplication of the urinary bladder wall without serous membrane, which divides the bladder into two halves. In this situation, one part is obstructive.

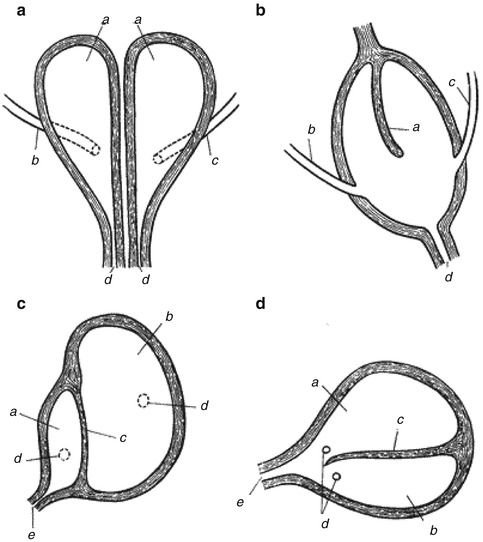

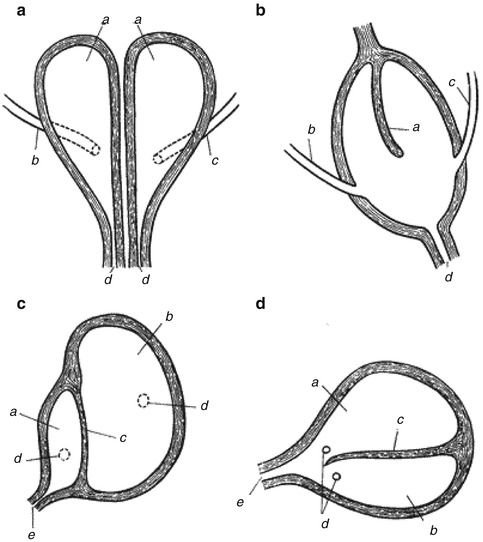

In case of duplicated urinary bladder, the bladder is divided into two parts by a longitudinal septum (Fig. 3.1a, b). Every part of the urinary bladder may be individually connected with its own urethra (the case of duplicated urethra); both halves of the bladder may open into a common urethra or only one-half of the bladder opens into the urethra (Fig. 3.1c, d). Diagnosis may be defined based on cystography. The cystogram shows shadows of the two halves of the urinary bladder separated with a septum which has an oval outline in the area of its top. This shape of the bladder shadow is similar to the heart symbol. A still rarer case of abnormality is the sandglass-shaped bladder: In the cystogram the shadow of one-half of the bladder is located above the other in the craniocaudal direction.

Fig. 3.1

Schemes of complete and incomplete duplication of the urinary bladder. (a) Complete duplication of the urinary bladder: а urinary bladders, b right ureter, c left ureter, d two individual urethras. (b) Incomplete duplication of the urinary bladder: а septum, b right ureter, c left ureter, d urethra. (c) Complete duplication of the urinary bladder in case a frontal septum is present: а front cavity, b rear cavity, c septum, d ureteral orifices, e urethra. (d) Incomplete duplication of the urinary bladder in case a frontal septum is present: а front cavity, b rear cavity, c septum, d ureteral orifices, e urethra (After Pytel and Pytel [6])

False or acquired UBD develop in patients who have had a long-term disturbance of urine discharge from the bladder which appears as urinary difficulty that is most often observed in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia.

3.1 Epidemiology

Congenital UBD are found rarely; according to results of autopsy of children, the rate is 1:100; they are more often found in boys than in girls and much more often in men than in women. The cause of congenital UBD formation is supposed to be development abnormality or influence of certain congenital factors such as trauma and retention of urine during the antenatal period. The rate of acquired diverticula development correlates with the incidence of diseases which cause infravesical obstruction (benign prostate hyperplasia, urethra stricture, sclerosis of urinary bladder neck, prostate sclerosis, etc.). It was discovered that every fifth patient which had surgery for infravesical obstruction developed UBD; however, only 15 % of those diverticula required surgical treatment [7–9].

3.2 Classification, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

The most common classification is dividing diverticula into congenital or true diverticula and acquired or false diverticula. The cause of development of true diverticula as the urinary bladder abnormality is malformation of the urinary bladder wall due to the influence of factors such as a trauma and urine retention during the antenatal period. The rate of acquired or false UBD development correlates with the incidence of diseases which cause infravesical obstruction (benign prostate hyperplasia, urethra stricture, sclerosis of urinary bladder neck, prostate sclerosis, etc.). Development of acquired UBD was observed in every fifth patient which had had surgery for infravesical obstruction.

Apart from the etiology of congenital and acquired UBD, the following criteria are also used for their type division: diverticulum wall containing a complete set of layers or only mucosa, number of diverticula and their size, presence or absence of a sphincter, etc. This classification implies different etiologies of true and false diverticula. The former are considered to be a consequence of dysembryogenesis, and the latter—a result of infravesical obstruction. However, there is a number of works where this classification is subject to valid criticism. The provided evidence includes observations of acquired diverticula that contained a full set of layers characteristic of the bladder wall and of congenital diverticula that consisted only of mucosa. In this case the etiology of acquired and congenital diverticula looks similar—formation of diverticula depends on two factors: congenital, weakness of certain parts of the urinary bladder, and acquired, urinary difficulty.

Anatomical features which before were considered as parameters for UBD classification into congenital and acquired ones, such as different structure of walls of congenital and acquired diverticula, presence of a sphincter in the congenital diverticulum neck, and multiplicity of acquired diverticula, are considered to be invalid by the majority of authors, since congenital and acquired UBD cannot be differentiated from each other at the morphological level [10, 11].

A similar study of the urinary bladder wall revealed that the wall was not developed equally in all parts of the bladder [3]. Noted that “…the urinary bladder has parts, where diverticula are found most often (area of ureteral orifices, the front and the rear walls), that feature a weaker development of muscles…” [3]. As for the sphincter of the diverticulum, the majority of authors deem that it is formed by connivent muscles of detrusor; thus, it cannot be called a true sphincter. Contractions of the detrusor during urination prevent the diverticulum from complete voiding, and residual urine accumulates in it. This caused describing UBD as “urine trap.” In spite of differences in views on UBD etiology, it should be said that up to now division of diverticula into true and false ones is the most common classification.

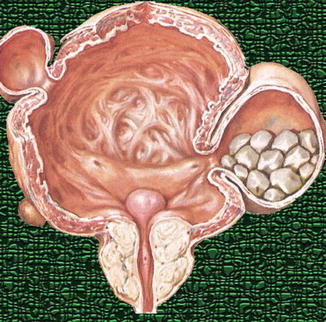

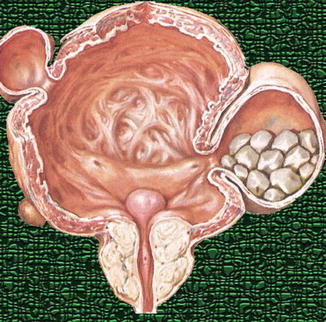

Thus, UBD can develop both during antenatal and postnatal life; however, the mechanism of their formation is the same: on the one hand, a weakness of certain bladder parts and, on the other hand, an obstruction to the bladder voiding (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

Fig. 3.2

Urinary bladder diverticula resulting from urinary difficulty which was caused by prostate adenoma (trilobe hyperplasia, detrusor hypertrophy). Stones in the diverticulum

3.3 Clinical Diagnostics

In case no symptoms appear, which is typical for the majority of UBD cases, the diverticulum is discovered “accidentally,” nowadays most often during USG examinations. Previously UBD were incidentally discovered during cystoscopy or cystography.

Many authors note that in case of UBD no typical clinical presentations are observed and infravesical obstruction symptoms prevail mostly.

The main UBD symptoms are urinary difficulty (up to complete urine retention), two-stage urination (urine is discharged first from the bladder and then from the diverticulum), or urination with Courvoisier procedure; these symptoms are observed not often.

UBD clinical presentations are induced by complications of this disease, such as overlay of infections and lithogenesis, compression of adjacent organs, hematuria, and ureterohydronephrosis. Vesicoureteral reflux may develop if the diverticulum is located in the area of ureteral orifice when its closing function is affected. Until complications arise, the diverticulum usually remains completely latent [5, 10].

Also the following rarer UBD complications are described: acute urine retention, acute renal failure, and urinary stasis with consequent tumoral degeneration. It is believed that the mucosa of the diverticulum is more subject to metaplasia which results from stasis of urine and a chronic infection. According to data by a number of authors, malignant tumors develop in 3–7 % of UBD [12–17].

3.4 Diagnostic Imaging

The methods used for diverticula visualization and diagnosis confirmation are ultrasonography, ascending and descending cystography, computer-aided tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging [6, 20].

Urinary bladder ultrasonography is one of the leading methods of diverticula diagnostics which displays an echo-free outpouching that protrudes outside the urinary bladder outlines (Figs. 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree