(1)

Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA

Abstract

Malignancy of the vagina is usually metastatic, and less commonly primary, in origin. Vaginal malignancy is usually metastatic, and less commonly primary, in origin. Primary and metastatic vaginal malignancies are reviewed with an emphasis on the imaging appearance of the vaginal tumor, nodal disease, distant metastases and post treatment changes.

Malignancy of the vagina is usually metastatic, and less commonly primary, in origin [1]. Metastases to the vagina usually originate from other sites in the genital tract such as the cervix, vulva, endometrium and ovary, and can also occur from non-gynecologic sites such as the rectum and breast [2]. Tumor spreads to the vagina by direct extension from adjacent viscera or by hematogenous route from distant malignancies.

Primary malignancies of the vagina account for less than 5 % of female genital tract cancers [1, 2]. Squamous cell cancer, the most common type, is seen in over 85 % of cases [1, 3]. The remaining tumors include melanoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, and less common histologies such as undifferentiated and small cell tumors, and lymphoma. Squamous cell cancer and melanoma usually occur in postmenopausal women, whereas adenocarcinoma predominates in young women [2]. A subtype of adenocarcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, is associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common type of sarcoma affecting infants and young girls.

Patients with vaginal malignancy can present with vaginal bleeding or discharge, or the tumor may be detected during screening for cervical cancer [2]. The tumor is often located in the posterior upper third of the vagina and tends to be multicentric [1, 2]. It can grow to directly involve surrounding soft tissues and adjacent viscera such as the paracolpos, cervix, urethra, bladder, rectum, and pelvic side wall. The lymphatic drainage follows the embryologic origins of the vagina: The upper two-thirds is derived from the müllerian tract, and the distal third arises from the urogenital sinus [3]. Lymphatic spread from the upper vagina is to the external and internal iliac nodes, followed by the common iliac and para-aortic nodes [4, 5]. The lower vagina drains to the superficial inguinal nodes, followed by the deep inguinal nodes and then superiorly to the external iliac nodes [4]. Hematogenous spread to lungs, liver, and bone is typically seen in advanced disease [2, 3].

Radiation therapy, via brachytherapy or external beam therapy, is the primary treatment modality used in most patients [2]. Surgery with radical vaginectomy and lymphadenectomy can be considered for patients with small, early-stage tumors, and pelvic exenteration for those with recurrent or advanced disease [2]. Complications of therapy include vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas and vaginal stenosis. Patient prognosis depends on the stage of disease (Tables 4.1 and 4.2). Patients with high stage, tumors larger than 4 cm, or melanoma have a poorer prognosis [2, 3].

Vaginal lesions seen on physical examination can be assessed with ultrasound or MRI. Cysts and solid masses are differentiated with ultrasound, but MRI is better for characterizing lesions and assessing local extension of the tumor [6]. Gel can be used to distend the vagina on MRI to evaluate the wall thickness and for intraluminal masses [7, 8]. Imaging in the axial and sagittal planes demonstrates vaginal wall thickness, focal masses, and the relationship of a mass to adjacent anterior and posterior viscera. On MRI, the normal vagina has a T2 hyperintense inner mucosal layer followed by a T2 hypointense muscular layer with surrounding outer adventitial tissue, which has a prominent T2 hyperintense venous plexus [3, 9–12]. The posterior fornix is typically situated more cranially than the anterior fornix on sagittal images. On axial images, the normal vagina has an “H” configuration, with the lateral walls directed anteriorly towards the pubis.

Table 4.1

FIGO staging of vaginal carcinoma

FIGO category | Description |

|---|---|

I | The carcinoma is limited to the vaginal wall |

II | The carcinoma has involved the subvaginal tissue but has not extended to the pelvic wall |

III | The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic wall |

IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum; bullous edema as such does not permit a case to be allotted to Stage IV |

IVa | Tumor invades bladder and/or rectal mucosa and/or direct extension beyond the true pelvis |

IVb | Spread to distant organs |

Table 4.2

TNM staging of vaginal carcinoma

TNM category | Characteristics |

|---|---|

Primary tumor (T) | |

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) |

T1 | Tumor confined to vagina |

T2 | Tumor invades paravaginal tissues but not to pelvic wall |

T3 | Tumor extends to pelvic wall |

T4 | Tumor invades mucosa of the bladder or rectum and/or extends beyond the true pelvis (bullous edema is not sufficient evidence to classify a tumor as T4) |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Pelvic or inguinal lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastasis (M) | |

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/Prognostic groups | |

0 | Tis – N0 – M0 |

I | T1 – N0 – M0 |

II | T2 – N0 – M0 |

III | T1-T3 – N1 – M0 or T3 – N0 – M0 |

IVA | T4 – any N – M0 |

IVB | Any T – Any N – M1 |

4.1 Normal Anatomy

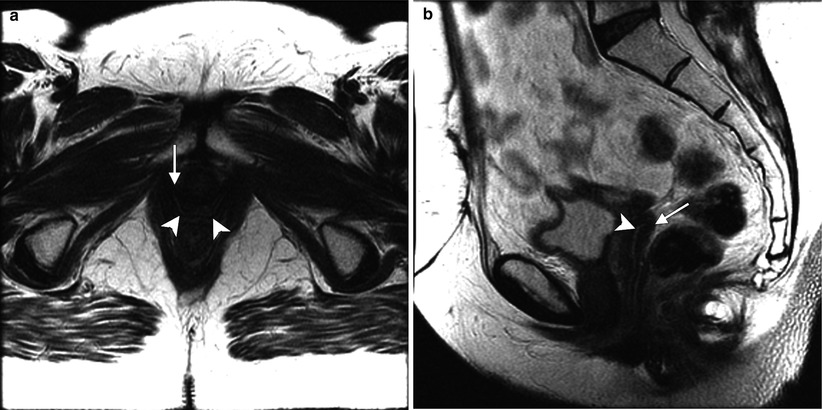

Fig. 4.1

Transverse (a) and sagittal (b) T2-weighted MR images of the pelvis without fat saturation show central hyperintense mucosa (arrowheads) and outer hypointense muscular layer (arrows), as well as “H”-shaped configuration of the vagina

4.2 Stages of Disease

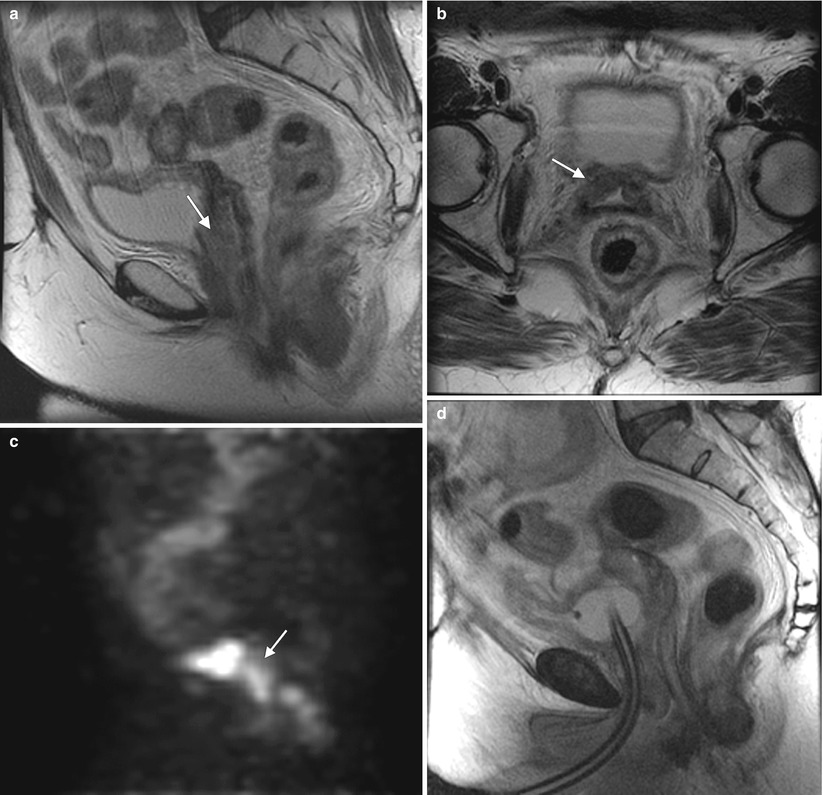

Fig. 4.2

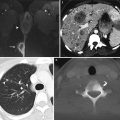

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina, stage I at presentation. Perimenopausal patient with abnormal Pap smear and colposcopy. Sagittal (a) and axial (b) T2-weighted MR images of the pelvis show abnormal intermediate signal intensity and nodular thickening of the anterior vaginal wall (arrow) due to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Increased activity was noted in the vagina (arrow) on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (c). The patient was not felt to be a surgical candidate and was treated with radiation for stage I vaginal cancer. Followup MRI performed 7 months later showed diffuse thickening of the bladder and vagina, probably due to radiation. There was also new soft tissue in the left vesicovaginal space, inseparable from the bladder, that was suspicious for local extension of tumor (arrow): sagittal (d), axial (e), and coronal (f) T2-weighted images and a sagittal postcontrast T1-weighted image (g) with fat saturation. A Foley catheter is also noted in the bladder, as well as artifact at the vaginal cuff from a prior procedure. Followup CT images 14 months after the initial scan (h–j) show additional progression, with a necrotic central pelvic mass (arrow) involving the bladder and vagina, bilateral external iliac nodes (arrows), and a lung metastasis (arrow). Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is likely to be associated with infection with the human papillomavirus [1, 2]. Most patients are postmenopausal and have a mass in the proximal posterior vagina, which can be ulcerative or exophytic. A variant is verrucous carcinoma, which appears as a fungating mass with local spread [2]. On MRI, the mass tends to have intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images and to be homogeneous [1]. The lumen is expanded with exophytic tumors

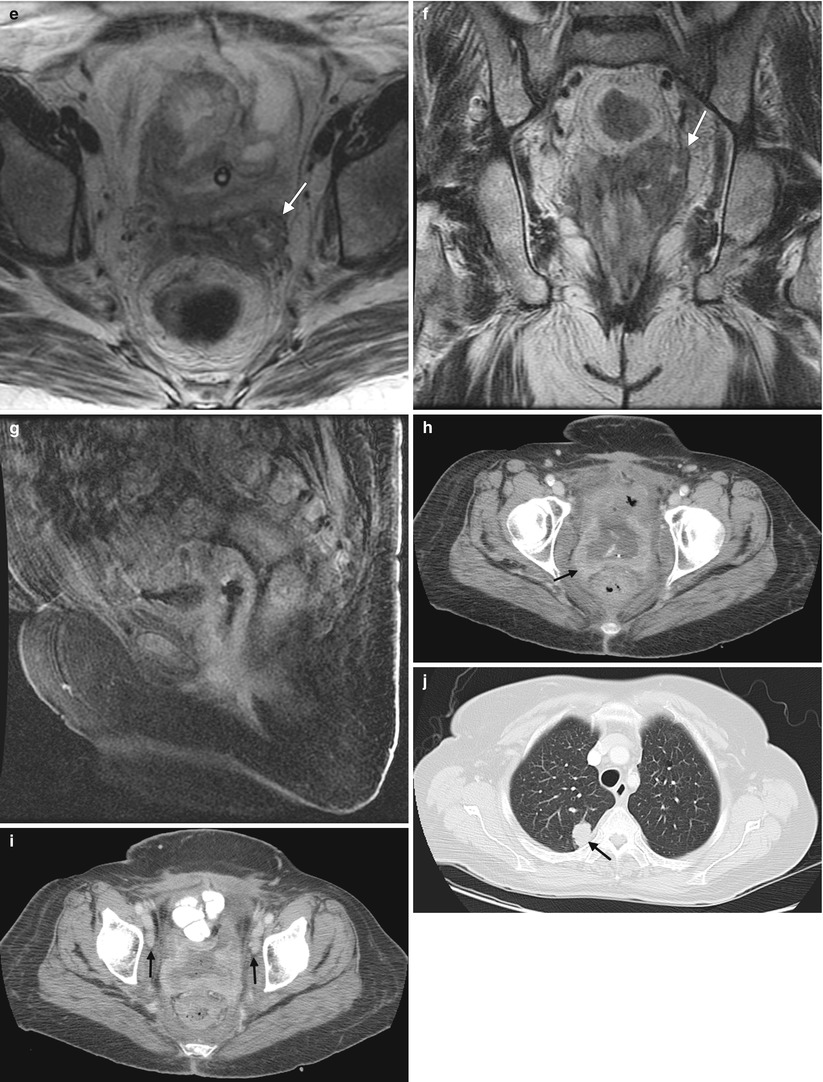

Fig. 4.3

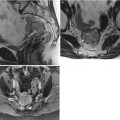

Adenocarcinoma of the vagina, stage II at presentation. This postmenopausal patient presented with vaginal bleeding and a protruding vaginal mass. Sagittal (a), axial (b), and coronal (c) T2-weighted MR images with fat saturation show a mass within the vagina with intermediate signal intensity (arrow). The mass distends the vaginal cavity, with loss of definition of the left anterior vaginal wall. It abuts the urethra and extends anteriorly to the retropubic region (arrowhead). Coronal T1-weighted images before contrast (d) (without fat saturation) and after contrast (e) (with fat saturation) show enhancement (arrow). The vaginal mass and a short segment of urethra were excised, revealing a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient was treated with radiation but recurrence occurred 2 years later, and she underwent a pelvic exenteration with no disease on subsequent followup. Adenocarcinoma represents the majority of vaginal carcinomas in young patients and typically occurs in the second decade of life [2]. Its possible origin is from adenosis, endometriosis, periurethral glands, or wolffian rests [1]. A variant is clear cell carcinoma, which is associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Adenocarcinoma tends to occur in the proximal anterior vagina and can be a polypoid mass or can appear as wall thickening [1]. On MRI, the mass has been described as hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with heterogeneous enhancement [14]. There is disruption of the normal low signal intensity of the vaginal wall with spread of the tumor to the paravaginal tissues [1]

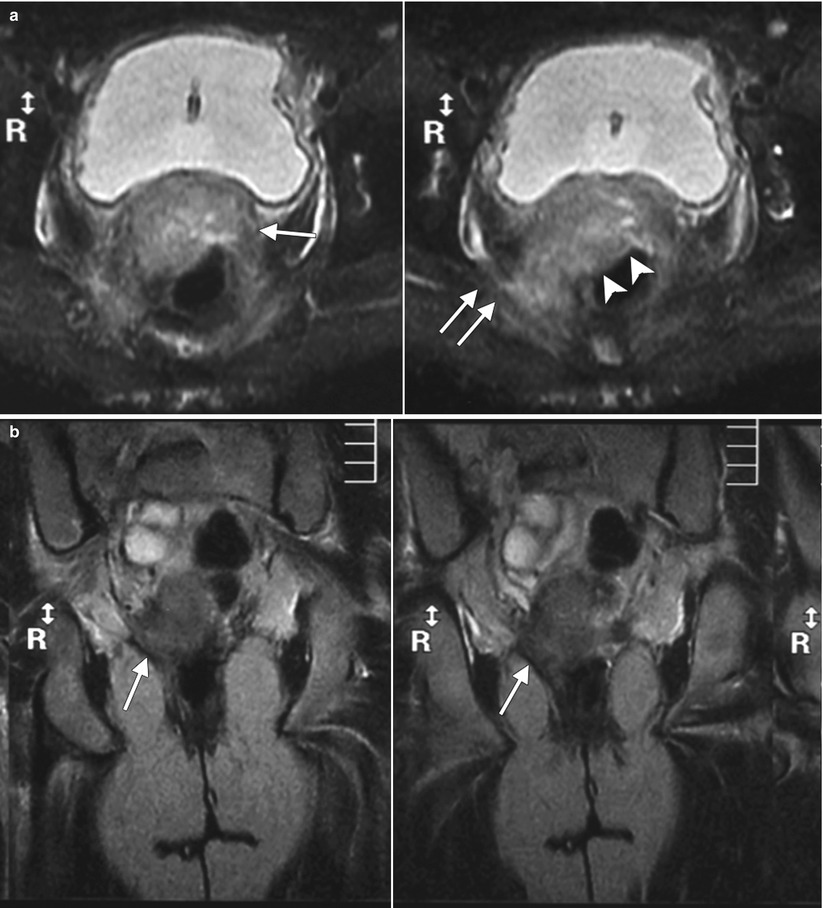

Fig. 4.4

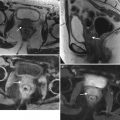

Poorly differentiated carcinoma with sarcomatoid features of the vagina, stage III at presentation, in a perimenopausal patient. The patient had been treated with chemotherapy and radiation for colorectal carcinoma approximately 15 years previously and now presented with vaginal bleeding. (a) Axial T2-weighted MR images with fat saturation show a mass in the vagina (arrow), which extends into the perirectal fat and involves the right rectal wall (arrowhead) and pelvic musculature (double arrows). (b) Coronal T2-weighted images show right perirectal extension (arrow). (c, d), Precontrast and postcontrast T1-weighted images without fat saturation show enhancement of the mass (arrow). In summary, there is a vaginal mass with ill-defined margins and local extension to involve the right rectal wall and pelvic musculature. The patient underwent a total pelvic exenteration. At surgery, the vaginal tumor involved the cervix, bladder wall, rectal wall, and levator muscle. The bladder and rectal mucosa were benign. Local spread of tumor is best seen on MRI and on T2-weighted images in the axial and coronal planes or the oblique plane perpendicular to the long axis of the vagina [1]. The tumor tends to be higher in signal intensity than the bladder wall and rectal muscle, as well as the pelvic floor musculature. With erosion of the tumor into adjacent viscera, fistulas can be demonstrated as T2 hyperintense tracks with fluid as well as gas in the vagina

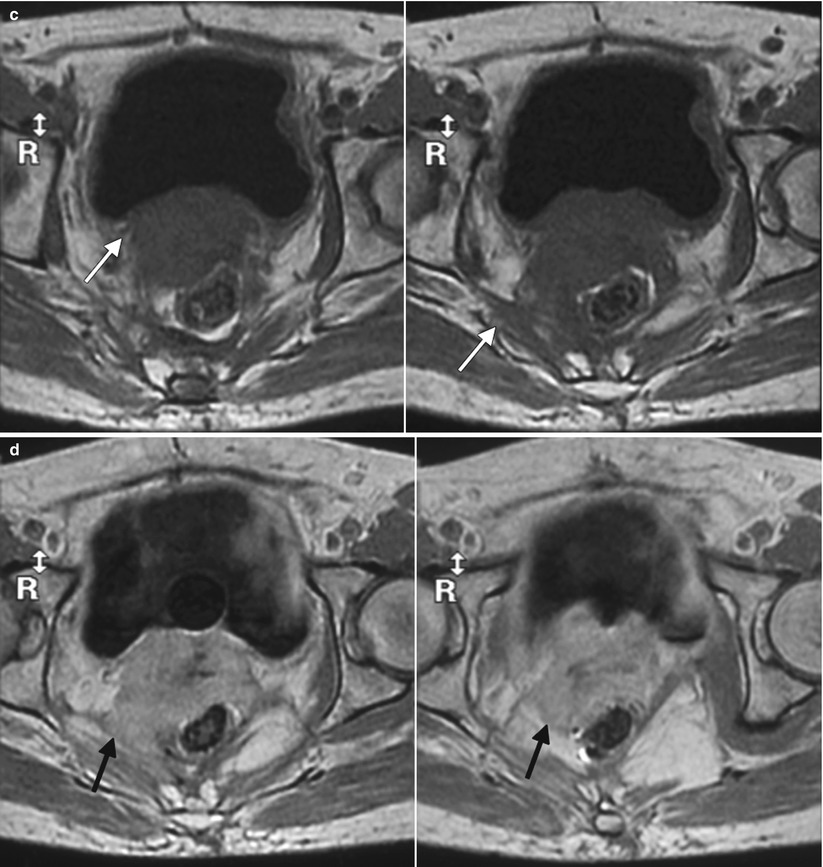

Fig. 4.5

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina, stage III at presentation. This postmenopausal woman presented with rectal and vaginal pain. A vaginal mass was seen on physical examination, and biopsy showed moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma. An axial precontrast T1-weighted image with fat saturation (a) and coronal T2-weighted images (b) show an infiltrative vaginal mass (arrow) involving the urethra and rectum and extending to the ischioanal fossa (arrowhead) and pelvic musculature. T1-weighted MR images using contrast with fat saturation in the sagittal (c), axial (d), and coronal (e) planes show enhancing ill-defined tumor (arrow). The patient was treated with chemotherapy and radiation

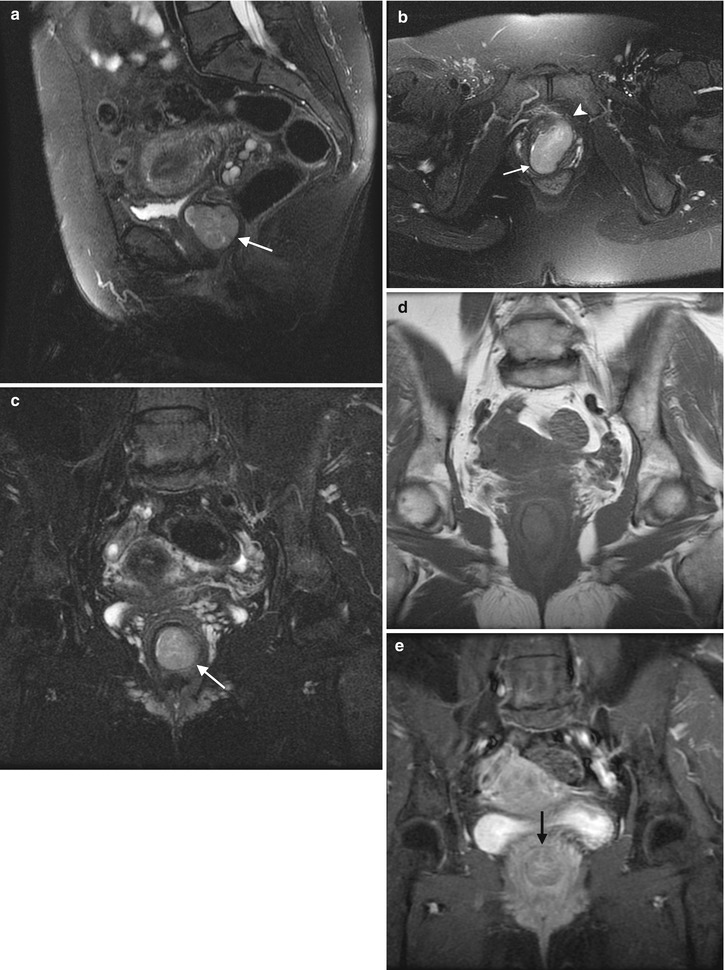

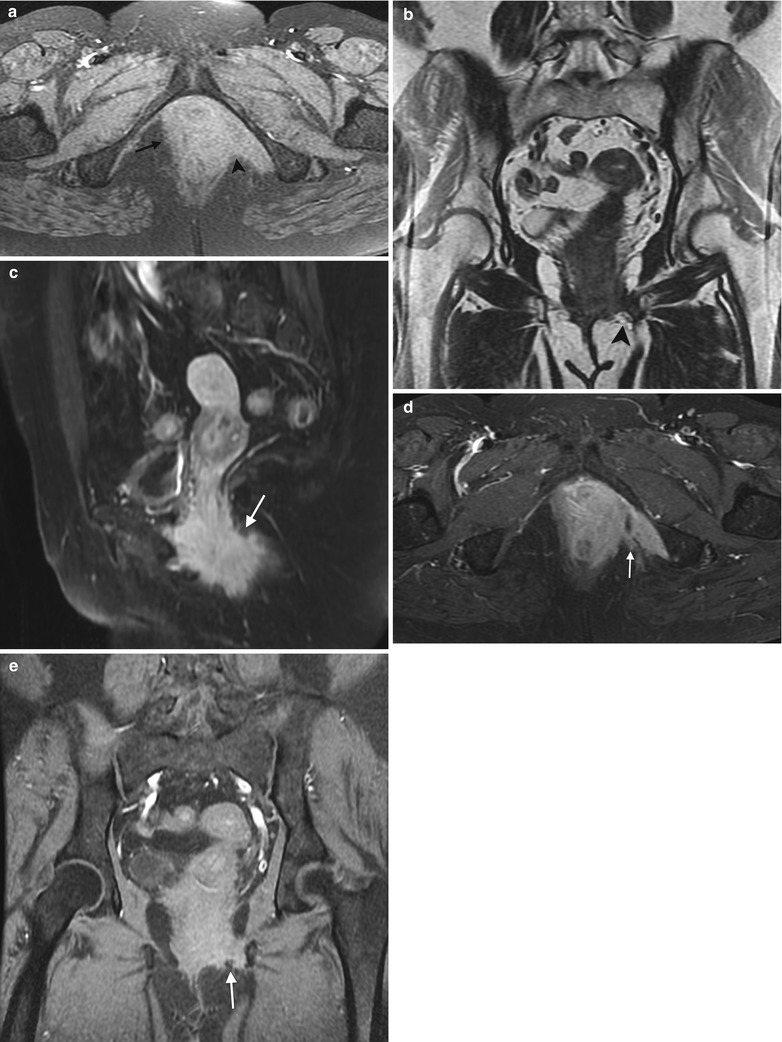

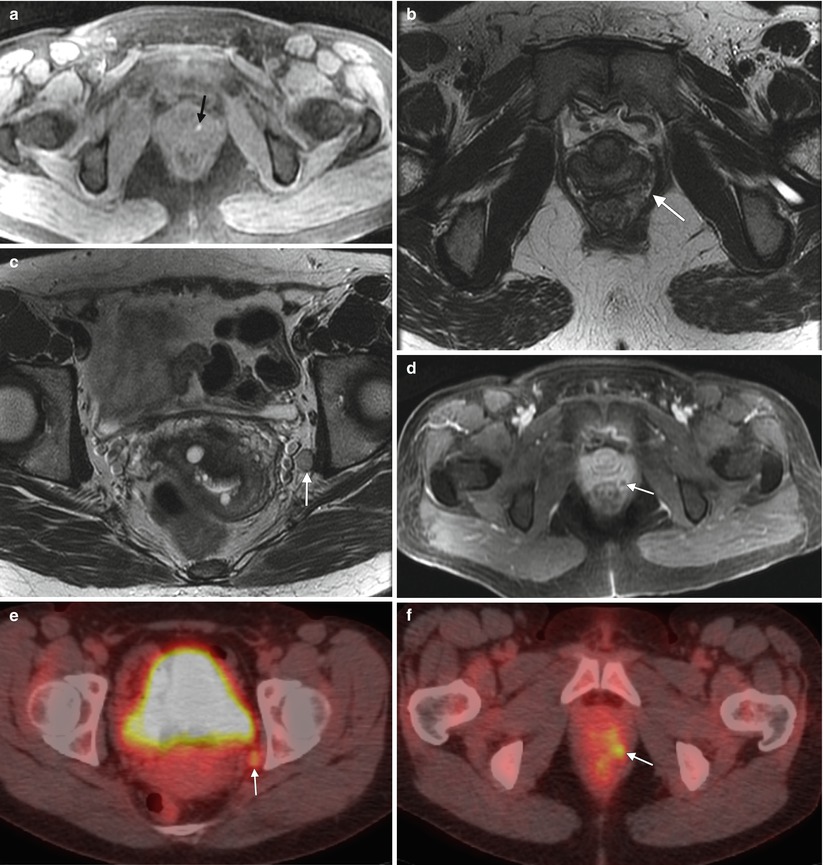

Fig. 4.6

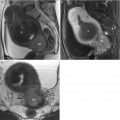

Melanoma of the vagina with nodal metastasis. This perimenopausal woman presented with vaginal bleeding and several pigmented vaginal lesions. Biopsy showed left vaginal wall melanoma with invasion. (a) An axial T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a T1-hyperintense focus in the left aspect of the vagina (arrow). (b, c), Axial T2-weighted images at different levels show soft tissue in the left rectovaginal space (arrow) and a left obturator node (arrow). (d) An axial postcontrast T1-weighted image with fat saturation shows enhancement of the rectovaginal nodule (arrow). (e, f) The obturator node (arrow) and perirectal nodule (arrow) were hypermetabolic on fused FDG-PET images. Biopsy of the pelvic node was positive for malignant melanoma, and the patient was treated with radiation as well as ipilimumab, a T-lymphocyte blocking antibody. Lymphatic spread from the upper vagina is to the obturator and external and internal iliac nodes, followed by the common iliac and para-aortic nodes [4]. The lower vagina drains to the superficial inguinal nodes, followed by the deep inguinal nodes and then superiorly to the external iliac nodes [4]. On MRI, nodes are evaluated by size and location. Nodes larger than 7–10 mm in short axis and in the expected drainage pathway may be due to metastatic disease. Evaluation with FDG-PET is helpful to identify malignant nodes. Malignant nodes may also appear heterogeneous and necrotic on CT scans

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree