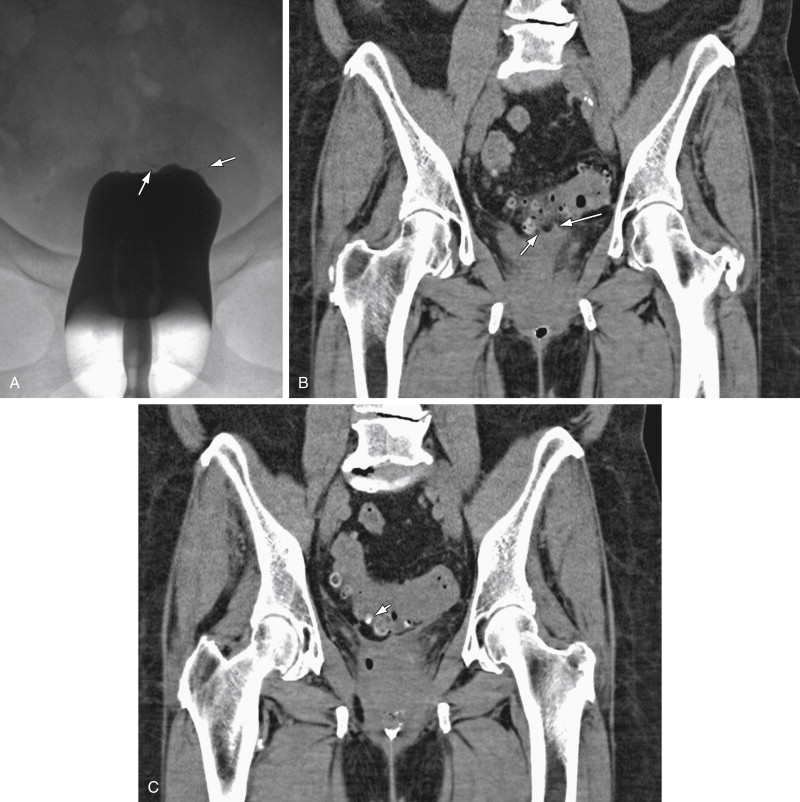

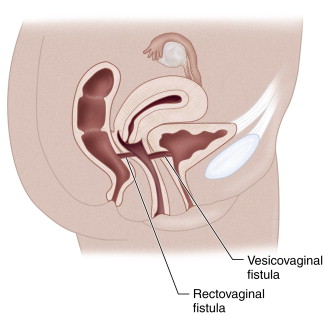

A vaginal fistula is a hole in the vagina and an abnormal tract leading to another structure, most commonly the bladder or rectum ( Figure 26-1 ). Vaginal fistulas also occur to the colon, small bowel, urethra, ureter, uterus or cervix, peritoneal cavity, or any other structure prone to this process as a result of surgery, trauma, inflammatory process, malignancy, or radiation treatment.

Disease

Prevalence and Epidemiology

According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 women develop fistulas each year as a result of obstetric trauma, and 2 to 3 million women in developing countries currently live with fistula injuries, largely related to prolonged labor lasting days, and in some countries as a result of traumatic sexual assaults.

In developed countries, vaginal fistulas resulting from obstetric trauma decreased markedly in the late nineteenth century because of the introduction of cesarean delivery and other improvements in obstetric care. Vaginal fistulas in developed countries have increased since the 1950s as a result of hysterectomies and diverticulitis of the colon.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Any condition that causes loss of blood flow and damage to the vagina or an adjacent organ can result in fistula formation, such as pressure necrosis from prolonged labor or inflammatory bowel disease. The vaginal suture line from a total hysterectomy, particularly when combined with any other predisposing condition in the pelvis, can lead to vaginal fistula.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Vaginal fistula is heralded by passage of thin watery or foul-smelling discharge or gas from the vagina, or by abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

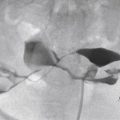

Vaginography is the procedure of choice when vaginal fistula is suspected ( Figures 26-2 and 26-3 ).

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

Vaginography is performed by inflating a barium enema balloon or 30-mL catheter within the vagina, and introducing water-soluble contrast agent during fluoroscopic visualization ( Figure 26-4 ). If the woman has not had a hysterectomy, the cervix must be occluded, which can be accomplished by inflating a 2- or 3-mL balloon catheter in the cervical canal (similar to the performance of a hysterosalpingogram but without introducing contrast agent into the cervix). Vaginography is more sensitive than barium studies and excretory urography for diagnosing vaginal fistulas (see Figure 26-4 ).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is usually not indicated for vaginal fistulas.

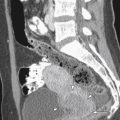

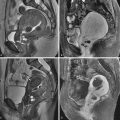

Computed Tomography

A computed tomographic (CT) scan performed for pain, mass, or other symptoms can demonstrate orally administered contrast agent or air within the vagina, which suggests a diagnosis of vaginal fistula in the proper setting. CT can also demonstrate contiguous pelvic mass, adherent thickened bowel, or radiation changes, suggesting the possible cause of the fistula.

The main utility of CT scan is after fluoroscopic vaginography, to better demonstrate the course and nature of a fistula tract diagnosed by the vaginogram. CT scan interpretation is sometimes difficult because of preexisting dense stool ( Figure 26-5 ).