Raj Ayyagari • Jeffrey S. Pollak

BACKGROUND

Pathophysiology

By far the most common genitourinary venous pathologic entity that lends itself to embolization therapy is the varicocele, an abnormal and often symptomatic tortuous dilation of the pampiniform venous plexus in the male scrotum. Varicoceles are thought to be caused by acquired incompetence or congenital lack of one-way valves in the gonadal vein (also known as the internal spermatic vein), resulting in abnormal retrograde reflux of venous blood from the inferior vena cava or renal vein, down the gonadal vein, and into the pampiniform plexus surrounding the testicle. Prolonged and repetitive reflux of flow results in abnormal dilation of the venous plexus, manifesting as an often palpable and sometimes painful nest of tortuous and dilated veins in the scrotum, giving a so-called “bag of worms” appearance (Fig. 53.1). The pathophysiology is similar to that seen in lower extremity varicose veins.

The prevalence of varicoceles in the general male population is estimated to be 15% to 17%, increasing in incidence with age from less than 1% of boys younger than 10 years of age up to approximately 15% of boys in late adolescence.1 Approximately 90% of patients have left-sided varicoceles, and about 10% of patients’ varicoceles are bilateral.2 Right-sided varicoceles are rare and found in less than 1% of patients.1 However, most varicoceles are asymptomatic.

There are multiple theories about the left-sided predominance of varicoceles, and indeed, the pathophysiology is likely multifactorial. These theories are best understood when considering the normal anatomy of the gonadal veins (Fig. 53.2). The left gonadal vein is one of the longest veins in the body, ascending from the scrotum out of the inguinal canal and up through the retroperitoneum to join the left renal vein at a perpendicular angle in 80% to 90% of the population (the remainder generally join the inferior vena cava directly).3 The right gonadal vein follows the same general course in the pelvis but then commonly joins the inferior vena cava directly at an oblique angle. The intravascular pressure within the left renal vein is often increased compared to that of the right renal vein because the left renal vein is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, the so-called “nutcracker” effect. This elevated left renal vein pressure and perhaps the anatomical configuration of the venous junction itself are thought to contribute to higher resistance outflow of the left gonadal vein and thus to abnormal reflux of venous blood down the left gonadal vein.4 This pathophysiology is thought to be further exacerbated by situations that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as repetitive heavy lifting, coughing, playing certain musical instruments, and even prolonged standing. Some authors believe that there may even be a heritable component that predisposes people to venous incompetency in general and to varicoceles in particular.5 For these reasons, left-sided and bilateral varicoceles seldom need further workup, whereas an isolated right-sided varicocele or the sudden onset of any varicocele should prompt further investigation with cross-sectional imaging to look for (1) conditions that would cause venous outflow obstruction, such as caval or renal vein thrombosis; (2) conditions that would cause obstruction of the right gonadal vein, such as malignant retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy; or, rarely (3), situs inversus. By the time the problem has become evident, normal antegrade venous flow through the gonadal vein may be completely absent, with the venous drainage of the affected hemiscrotum occurring via other collateral scrotal veins such as the external pudendal, cremasteric, and deferential veins. The external pudendal vein drains into the greater saphenous vein, the cremasteric vein drains via the inferior epigastric vein into the external iliac vein, and the deferential vein drains via the superior vesicular vein into the internal iliac vein.

Diagnosis

Varicoceles are usually diagnosed clinically, with patients presenting with palpable and often painful scrotal varicosities. A physical examination should be performed with the patient standing, with careful palpation of both sides of the scrotum done with and without the patient performing a Valsalva maneuver. A grading system for varicocele severity proposed by Dubin and Amelar6 is frequently used, with grade 0 describing a varicocele that is nonpalpable but visible on ultrasound; grade 1 describing a small varicocele palpable only with Valsalva maneuver; grade 2 describing a moderate-sized varicocele palpable without Valsalva maneuver but not visible; and grade 3 describing a large varicocele that is visible without Valsalva maneuver.

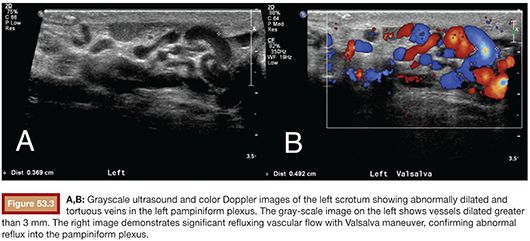

Real-time grayscale scrotal ultrasound with color-flow Doppler is used to confirm the presence of a varicocele or to detect a small varicocele not evident on physical exam (Fig. 53.3). Images are obtained both during rest and Valsalva maneuver to identify abnormal reflux. Prolonged Valsalva-augmented venous reflux longer than 1 second is considered diagnostic of a varicocele.7 Pampiniform plexus vessel diameter of 3 mm or greater, indicative of abnormal venous distension, is also considered diagnostic.7 These findings will often be present with the patient supine, but if there is a question, visualizing the scrotal vessels with the patient upright will often augment the findings. Gonadal venography generally does not play a role in diagnosis and is performed only during the actual endovascular treatment of a varicocele.

Indications for Treatment

Any symptomatic varicocele found either on physical exam or with ultrasound merits treatment. However, special consideration should be given to those patients who present with coexisting problems such as inguinal hernias or complex pain syndromes including chronic postoperative groin pain. Such patients should be counseled that treatment of the varicocele may only partially treat their pain at best, and it is appropriate to also refer such patients to a general surgeon or urologist for more complete evaluation of their symptoms before formulating a treatment plan.

Varicoceles are sometimes discovered in boys being evaluated for hypogonadism, and indeed, testicular atrophy can sometimes be reversed or prevented if effective treatment of the varicocele is performed in a timely fashion. 8–10 Varicoceles are also frequently discovered in adult males undergoing workup for infertility, with a prevalence of 30% to 40% in such patients.11,12 Infertile men with varicocele are often found to have decreased sperm motility, decreased sperm count, and increased abnormal sperm morphology. The detrimental effect of a varicocele in both situations of hypogonadism and infertility is thought to be related to the elevated ambient temperature around the affected testicle brought on by the surrounding abnormally engorged veins. In the case of infertility, the abnormally elevated scrotal temperature is thought to affect sperm production in both testicles, even when the varicocele is unilateral.13 This phenomenon would tend to undermine other theories that invoke etiologies such as the reflux of toxic metabolites or hypoxia due to venous stasis, as such insults would seemingly affect sperm production on the affected side only given the sparse cross-collateral venous flow between the left and right scrotum. Obliteration of the abnormally engorged veins is reasoned to restore a normal ambient scrotal temperature and to eliminate any reversible detriment on testicular size and sperm production. Indeed, a growing number of studies support a causal relationship between varicoceles and decreased sperm quality by demonstrating positive effects on semen quality after varicocele treatment.14,15 However, varicoceles have only been shown to be associated with infertility when they are palpable.16 Furthermore, the positive impact of varicocele treatment on actual fertility remains controversial.17

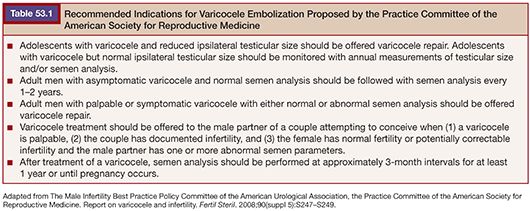

The workup for patients with hypogonadism centers on longitudinal ultrasonographic evaluation of testicular size and growth, whereas workup for patients with infertility should include at least two longitudinal preprocedural semen analyses. Monitoring and treatment recommendations for patients with varicocele and hypogonadism or infertility have been delineated by the Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and are summarized in the following table (Table 53.1).18

Thus, in summary, the treatment of varicoceles is warranted for indications including scrotal pain, male infertility in the presence a palpable varicocele, and persistent hypogonadism in adolescent patients. Treatment is also appropriate for any patient who is uncomfortable with the cosmetic appearance of the varicocele, and indeed, some varicoceles can become quite large. Furthermore, varicocele embolization is warranted for any of the conditions mentioned earlier in the setting of recurrence after prior surgical attempt at varicocele ligation.

Once the diagnosis of varicocele has been confidently made and there is an appropriate indication for treatment, further preprocedural evaluation for a percutaneous embolization procedure is straightforward. Laboratory analysis to ensure appropriate clotting parameters (international normalized ratio and platelet level) and renal function (serum creatinine level or estimated glomerular filtration rate) is performed. If the patient is young and healthy with no other significant medical history, some authors will forgo such analysis. Clotting diatheses often can be effectively managed in the periprocedural setting with transfusions of blood products. Patients with borderline renal function can also be cautiously considered for embolization, given the relatively small amount of intravenous contrast used for the procedure. The only real contraindication to percutaneous varicocele embolization is a severe reaction to intravenous contrast, in which case surgical repair should be considered.

TECHNICAL DETAILS

There is no effective medical treatment for varicoceles. Treatment options for varicocele repair include surgical ligation and percutaneous embolization. Both treatments work by eliminating abnormal retrograde blood flow through the gonadal vein and down into the pampiniform plexus. Patients often wonder why occluding the main vessel that is supposed to drain the testicle is not harmful, or how blood flow will return from the testicle once this vessel is occluded. It is helpful to explain that by the time the diagnosis has been made, the gonadal vein has already effectively been “broken” and that there are other collateral scrotal veins such as the external pudendal, cremasteric, and deferential veins that have since been providing venous drainage for the testicle and will continue to do so after embolization.

Embolization Materials

Various embolization materials have been used for varicocele embolization and can broadly be categorized into mechanical occlusion devices, such as vascular coils and detachable balloons, and sclerosing agents, such as sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Sotradecol; AngioDynamics, Latham, New York). Coils and Sotradecol comprise the mainstay of embolization materials used in modern-day practice, although cyanoacrylate-based glue is a liquid embolic agent commonly used for this application in European centers. Polidocanol is another sclerosant agent used by some, although this agent is not available within the United States. Many of the remaining materials described in the following discussion are for historical interest only.

Platinum-based or nickel-chromium alloy coils are the most commonly used embolic agent and are deposited within the gonadal vein at various levels to provide a macrovascular-level mechanical occlusion and thus prevent reflux of venous blood down into the scrotum. These coils serve as thrombogenic agents, thus proper occlusion with such coils depends on the body’s ability to form clot effectively. These coils are manufactured in various shapes and sizes and come in both 0.035-in/0.038-in and 0.018-in varieties for use with either standard size 4-Fr or 5-Fr catheters or smaller microcatheters, respectively. Modern embolization coils are inert, magnetic resonance imaging–compatible, and have not been significantly associated with any adverse side effects. These points should routinely be mentioned to patients, who will often have concerns about having foreign objects implanted within them for the rest of their lives.

Recently developed detachable vascular occlusion plugs are highly effective devices that allow for greater precision of placement and more efficient occlusion, with one such device often providing an occlusion equivalent to several coils. However, such advantages usually have little practical significance in the low-flow, relatively peripheral gonadal vein and do not justify the current higher cost of such devices. In the past, tungsten coils and detachable balloons were used; however, these devices have been removed from the market due to unfavorable cost and efficacy profiles.

Many authors advocate the use of a chemical sclerosing agent for varicocele embolization, often in conjunction with vascular coil placement. 19–21 The most commonly used agents are sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Sotradecol) and sodium morrhuate, which are anionic surfactant detergents that act by causing an inflammatory disruption of the endothelial linings of the treated vessels and triggering the aggregation of platelets and granulocytes.22 Previously, application of these agents had been limited to the gonadal vein itself due to concerns for scrotal thrombophlebitis if the sclerosing agent passed below the level of the inguinal canal. Indeed, manual compression of the inguinal canal and balloon occlusion of the inferior gonadal vein during sclerosant injection used to be standard. However, reports of investigators injecting sclerosing agents directly into the pampiniform plexus with good results began to emerge, and now some authors advocate deliberate transvenous catheter injection of sclerosant into the pampiniform plexus itself, in conjunction with coil embolization.23 There is evidence that this combined technique provides better results, owing to the complementary macrovascular coil-mediated gonadal vein occlusion and the microvascular sclerosant-mediated pampiniform plexus sclerosis. 19–21 Indeed, the sclerosant liquid foam can pass into and treat small parallel channels not occluded mechanically by coils. The combined coil embolization and Sotradecol sclerosing technique is described in detail in the following discussion. In the past, other agents such as heated contrast, hypertonic glucose with monoethanolamine, and absolute ethanol were used, but these agents have fallen out of favor due to unfavorable pain and efficacy profiles.

Technique

Transvenous varicocele embolization can be performed as an outpatient procedure under intravenous moderate sedation using standard medications such as fentanyl and midazolam. The patient needs to be arousable and cooperative during the procedure to perform the Valsalva maneuver at times during the embolization. It is helpful to perform the procedure on a table that can be tilted to facilitate identification and cannulation of vessels that have competent valves and thus may not be immediately recognized. Vascular access can be obtained from either the right common femoral vein or right internal jugular vein, depending on operator preference. Jugular access can be ergonomically advantageous when bilateral or right-sided varicocele embolization is planned. Such access also eliminates the need to have the patient lay flat after the procedure and the small but slightly increased hematoma risk with femoral vein access. However, femoral vein access often proves more convenient when a unilateral left-sided varicocele embolization is planned.

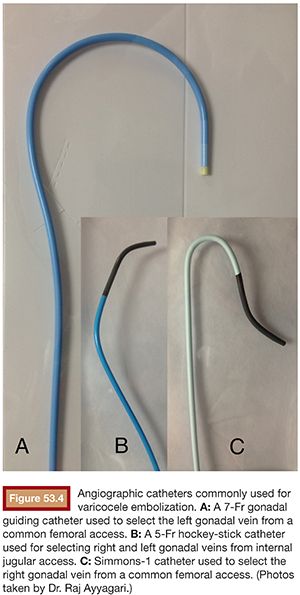

With either jugular or femoral access, the vein is accessed with ultrasound guidance and a 6-Fr or 7-Fr vascular sheath is placed. If treating the left side, the left renal vein is then easily selected with a 5-Fr hockey stick–shaped catheter (Terumo Medical Corporation, Somerset, New Jersey) from the jugular approach or with a 7-Fr Hopkins-customized gonadal guiding catheter (Cordis Corporation, Miami Lakes, Florida) from the femoral approach (Fig. 53.4). Either catheter can then be easily manipulated into the left gonadal vein using contrast injections to guide catheter positioning. If the 7-Fr gonadal catheter is used to select the left gonadal vein, a coaxial 5-Fr glide catheter is then used to navigate further down into the left gonadal vein. Renal venography done while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver is sometimes necessary to identify the left gonadal vein, and tilting the patient feet-down can help with this, especially if there is a competent valve in the gonadal vein. If treating the right side, the right gonadal vein can be selected from the jugular approach with a 5-Fr hockey stick–shaped catheter or with a Simmons-1 catheter from the femoral approach. Sometimes, the use of a coaxially placed microcatheter is necessary to navigate through difficult angles, narrowed or ectopic veins, or competent venous valves and is certainly necessary if treating the right gonadal vein via a femorally placed Simmons-1 catheter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree