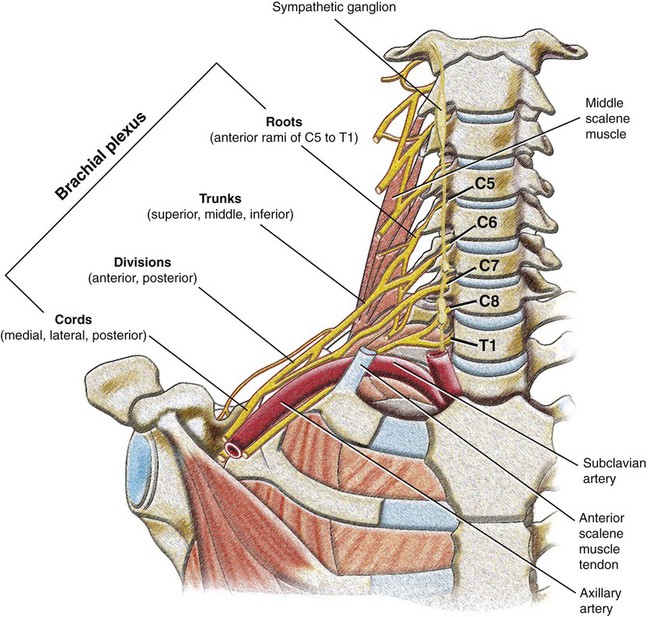

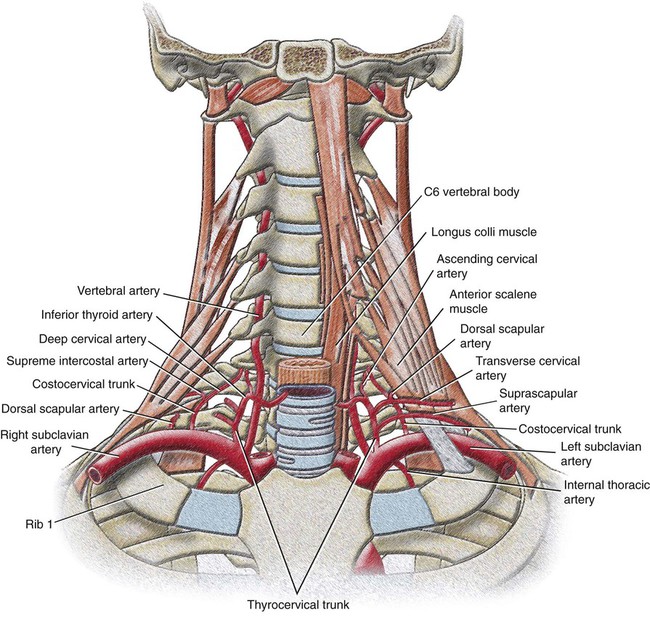

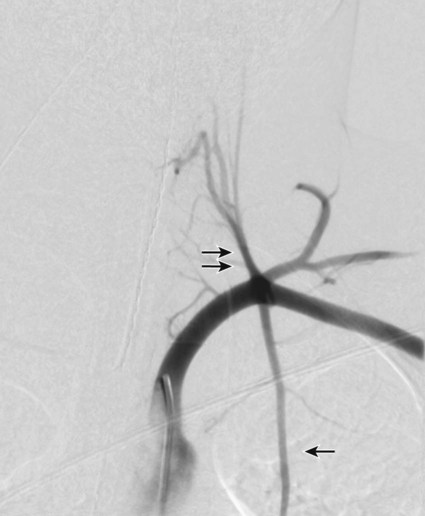

Imaging of the arterial and venous systems is an important component of the evaluation in many vascular disorders involving the upper extremity. In combination with clinical and laboratory observations, imaging provides crucial information for both diagnosis and management of these complex processes. This section will provide a brief overview of vascular imaging, including ultrasonography (US), computed tomographic angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and conventional angiography. For a complete discussion of vascular imaging techniques, please see Chapters 2 and 3. Real-time grayscale and color Doppler US is a useful, rapid, and portable imaging modality used to evaluate both the arterial and venous systems of the upper extremity. Arterial interrogation may be performed to assess for suspected limb ischemia, arterial stenosis, or patency of a hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula or graft. Assessment of the integrity of the venous side of the dialysis graft or fistula is also important, as is evaluation of thrombosis or compression of upper extremity veins. US can investigate flow hemodynamics along with vessel lumen and wall morphology. It is, however, operator dependent, does not fully evaluate upper extremity arterial inflow and central thoracic venous anatomy, and is limited in spatial display.1 CTA is a widely available technique that may be performed on all existing multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners (4 through 320 channels) to assess upper extremity vasculature. An excellent review on state-of-the-art techniques and clinical applications of CTA in the upper extremity by Hellinger et al. proposes four upper extremity CTA protocols: Aortic Arch with Upper Extremity Runoff, Upper Extremity Runoff, Upper Extremity Indirect CT Venography (CTV), and Upper Extremity Direct CTV based upon different clinical indications.1 This review highlights the various clinical scenarios in which CTA is useful and provides the technical parameters for acquisition, which are beyond the scope of this chapter. Contrast-enhanced MRA is a rapid noninvasive imaging technique that aids in treatment planning and preoperative mapping of various vascular disorders of the upper extremity.2 It evaluates vascular integrity and patency, which may be compromised in cases of trauma, atherosclerosis, vasculitis, and malignancy. MRA not only defines the site, degree, and extent of stenosis or occlusion but also demonstrates collateral pathways in these processes. Advantages of contrast-enhanced MRA in the upper extremity include its noninvasive nature, lack of flow artifact, multiangular projection capability, and ability to delineate the small vessels of the hand. Limitations of this imaging technique in the upper extremity include limited coverage of 40 to 50 cm, variable circulation time among individuals, and overlapping of the arteries and veins in the hand.2 Other considerations include the effects of partial volume averaging and susceptibility artifacts, which may lead to an overestimation of stenosis in small blood vessels. Conventional angiography is the gold standard for vascular imaging of the upper extremity, but it is an invasive procedure and is currently reserved for situations in which clinical questions remain despite information provided by the above-described noninvasive imaging modalities. It may also be used as the primary diagnostic modality when direct hemodynamic analysis is required for treatment planning or when there is intent to perform endovascular intervention in one combined procedure.1 The arterial blood supply of the upper extremity originates with the subclavian artery, whose typical diameter is 8 to 10 mm. The right subclavian artery arises from the brachiocephalic trunk, whereas the left subclavian artery is a direct branch from the aortic arch (Fig. 30-1). From its origin to the lateral border of the first rib, the subclavian artery supplies blood to the upper part of the chest, arms, and central nervous system (via the vertebral artery). The subclavian artery is divided into three segments based on its medial, posterior, or lateral relationship to the anterior scalene muscle. The first segments of the right and left subclavian arteries differ, whereas the second and third are nearly identical bilaterally. The first segment of the right subclavian artery begins at its origin from the brachiocephalic (innominate) trunk posterior to the upper border of the right sternoclavicular joint. It arches superolaterally, passes anterior to the extension of the pleural cavity in the root of the neck, and extends to the medial margin of the right anterior scalene muscle. It ascends variably 2 to 4 cm above the clavicle. The first segment of the left subclavian artery begins as a direct branch of the aortic arch after the origin of the left common carotid artery at the level of the third and fourth thoracic intervertebral disk spaces. It also ascends into the neck and arches laterally to the medial border of the left anterior scalene muscle. The second segment of the subclavian artery is posterior to the anterior scalene muscle. It is short and the most superior part of the vessel. The third segment descends from the lateral margin of the anterior scalene muscle and extends to the lateral border of the first rib, where it becomes the axillary artery. This portion is the most superficial part of the artery and lies partly in the supraclavicular triangle, the lower and smaller subdivision of the posterior cervical triangle. All major nerves that innervate the upper limb originate from the brachial plexus, a somatic plexus that begins in the neck and passes laterally and inferiorly over the first rib into the axilla. Medially to laterally, it is composed of roots, trunks, divisions, and cords. The roots are formed by the anterior rami of C5 to C8 and most of T1. The roots and trunks enter the posterior triangle of the neck by passing between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and lie superior and posterior to the subclavian artery. The proximal parts of the brachial plexus are posterior to the subclavian artery in the neck, whereas more distal regions of the plexus surround the axillary artery (Fig. 30-2). Variations in subclavian arterial anatomy are related to its origin and pathway. The right subclavian artery may arise above or below the sternoclavicular level as a distinct aortic arch branch, either the first or the last. When it arises as the first branch, it is in the position of a brachiocephalic trunk, as in the “classic” anatomy. If it arises as the last branch off the aortic arch, it ascends obliquely to the right and courses behind the trachea, esophagus, and right common carotid artery; alternatively in this scenario, it may pass between the trachea and esophagus. Occasionally, the left subclavian artery is combined at its origin with the left common carotid artery. Other variations in the pathway of the subclavian artery have also been described in relation to the anterior scalene muscle: perforating the muscle or, very rarely, passing anterior to it. Most of the branches of the subclavian artery arise from the artery’s first segment. Its branches include the vertebral artery, thyrocervical trunk, internal thoracic artery, and costocervical trunk (Fig. 30-3). These branches all arise from the first segment of the subclavian artery on the left. On the right, the costocervical trunk usually originates from the second segment of the subclavian artery. Additionally, on either side the dorsal scapular artery may arise from the third or, less often, the second segment of the subclavian artery or continue as the deep branch of the transverse cervical artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk. Variations involving the vertebral artery are related to its origin, usually a more proximal one. The left vertebral artery originates from the aortic arch between the left common carotid and the left subclavian artery in up to 5.8% of cases (Fig. 30-4). Its entrance into the cervical transverse foramen is also variable, but it most commonly enters at the level of the fifth cervical vertebra. Other rare variations involving the left vertebral artery that have been described include an origin from the aortic arch distal to the left subclavian artery, an origin from the left common carotid artery, or an origin from the external carotid artery. In less than 1% of cases, the right vertebral artery originates from the right common carotid artery or the aortic arch.

Vascular Anatomy of the Upper Extremity

Vascular Imaging of the Upper Extremity

Arterial Anatomy of the Upper Extremity

Subclavian Artery

Vertebral Artery

Vascular Anatomy of the Upper Extremity