33

Vascular Diseases of the Lower Gastrointestinal Tract

The interventional radiologist plays a critical role in the diagnosis and management of two conditions that affect the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract: hemorrhage and ischemia, both of which can manifest as acute, life-threatening illnesses or as chronic, debilitating or episodic conditions.

Lower GI Bleeding

Lower GI Bleeding

Bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract (distal to the ligament of Treitz) that comes to the attention of the vascular radiologist is due to diverticulosis in 50% of cases. Angiodysplasia, colon carcinoma, and benign polyps constitute most of the remaining cases. The workup of lower GI bleeding is divided into two broad categories: acute and chronic.

Acute lower GI hemorrhage

It is essential that a nuclear bleeding scan, either technetium-99 m (99mTc) red blood cells or sulfur colloid, be obtained to confirm that the patient is bleeding acutely. At our institution, a negative bleeding scan excludes the need for an emergent mesenteric angiogram, which is considerably less sensitive (0.05–0.1 mL per minute bleeding versus 0.5–1 mL per minute bleeding) (1,2). Emergency arteriography usually is performed after a positive bleeding scan because an angiogram can localize the site precisely (and sometimes the etiology) of bleeding and can be followed by catheter-directed therapy, thus avoiding urgent laparotomy. Rarely, patients are brought directly to surgery for hemicolectomy if the bleeding scan precisely localizes a colonic bleeding site. This generally occurs in patients who have a history of multiple acute lower GI bleeds in a vascular territory with a known structural lesion, typically diverticulosis. Barium has no role in the workup of acute GI bleeding because usually it is negative and precludes performing an angiogram.

A Foley catheter should be placed in the bladder for patient comfort and so that accumulating bladder contrast does not obscure the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and its branches in the pelvis. Sequencing of injections depends on the likely source of bleeding; that is, if a sigmoid source is suspected, the IMA is injected first.

Chronic bleeding

Patients presenting with chronic or recurrent lower GI bleeding usually are investigated first by barium studies and colonoscopy. Angiography is performed when these studies are negative, primarily to search for angiodysplasia; occasionally, small bowel tumors that have escaped detection by other means are identified at angiography.

Transcatheter diagnosis and therapy

If the patient is actively hemorrhaging (i.e., is passing blood per rectum and has a positive bleeding scan), the “acute” workup is directed first to localizing precisely the anatomic site of hemorrhage by visualizing a point of extravasation. Angiography should be performed expeditiously. Multiple injections may be required for precise localization, and the entire vascular territory at risk must be imaged. In our view, a single negative injection is insufficient. If the bleeding scan is negative, the bleeding has effectively ceased and the situation is managed as nonacute or “chronic.” The focus of the angiogram then will be to find a structural lesion, such as an angiodysplasia; extravasation will not be demonstrated, and the angiogram should be performed electively after optimization of the patient’s medical status.

It is not unusual for referring physicians to believe that a patient is actively bleeding if blood is being passed per rectum or a hematocrit decrement has occurred. In this situation, it may be tempting to forgo the bleeding scan and proceed directly to arteriography. In our view, this is usually a mistake because patients may cease bleeding spontaneously, pass residual blood per rectum, and exhibit a hematocrit drop on the basis of this most recent hemorrhage. A negative tagged red blood cell count (RBC) obviates the need for an emergent angiogram with its attendant risks to the patient. Conversely, a positive scan is more likely to demonstrate the site of active hemorrhage than is an angiogram, and thus this critical opportunity for localization may be lost if the nuclear study is omitted.1,2

Typically, patients with brisk, continuing lower GI bleeding are treated with intravenous vasopressin, which acts to constrict the smooth muscle of the GI tract. Intravenous vasopressin is thought to be effective for controlling variceal and left colon bleeding but less so for right colonic bleeding. If bleeding persists, nuclear scan localization and angiography are usually performed. If the arteriogram is positive, infusion of intraarterial vasopressin traditionally has been the angiographic treatment of choice. Intraarterial vasopressin is most effective in treating colonic diverticula, where it is effective in up to 90% of cases.3 Rebleeding eventually occurs in 30% of cases, but initial control by transcatheter infusion will avoid the morbidity of emergency surgery. This agent is most often started at 0.2 units per minute via a selective catheter in the superior mesenteric artery. If a 20-min follow-up angiogram shows no further bleeding, the infusion is continued and then gradually tapered off once the hemorrhage stops. If the initial dose is unable to control bleeding, the rate can be increased to 0.4 units per minute. Repeat angiography should ensure that there is no excessive vasospasm. With intraarterial (IA) vasopressin, patients may experience abdominal pain initially from bowel contractions. Contraindications to vasopressin include the presence of severe coronary artery disease or diabetes insipidus.3 Complications include the effects of both the agent and the indwelling catheter and occur in 5 to 9% of patients. Endoscopy has played an increasing role in diagnosis and management of acute and chronic bleeding, especially in the descending colon; it is often nondiagnostic when brisk bleeding obscures the field.

A mesenteric arteriogram performed after a positive bleeding scan may fail to demonstrate the bleeding site under the following circumstances:

- 1. The patient stopped bleeding between obtaining the nuclear scan and the angiogram.

- 2. The bleeding rate is below the threshold for detection by the angiogram.

- 3. The bleeding scan (or its interpreter) incorrectly localizes the bleeding; in about 15% of cases the source of acute “lower” GI bleeding is actually the duodenum.

- 4. There is variant anatomy: rarely, the middle colic artery arises from branches of the celiac axis.4

The first and second circumstances argue for prompt arteriography; the third and fourth mandate performing celiac arteriography if the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) arteriogram is negative.

Recently, the advent of 2 and 3 Fr microcatheter systems has allowed delivery of very peripheral microcoils, Gelfoam, or polyvinyl alcohol particles. Evidence suggests that this is effective and is associated with a low risk of bowel infarction,5,6 but the concept of mesenteric embolization remains controversial because the long-term effects of permanent occlusion (e.g., the development of ischemic strictures) are not yet known. Because bleeding often is self-limited, permanent arterial blockade seems less attractive to some than a reversible infusion. Embolization may represent a cost-effective alternative to 24 to 48 hr of transcatheter infusion therapy, which requires monitoring in the intensive care unit and may put the patient at risk for iatrogenic complications related to the catheter. In many practices, embolization is now preferred over infusion.

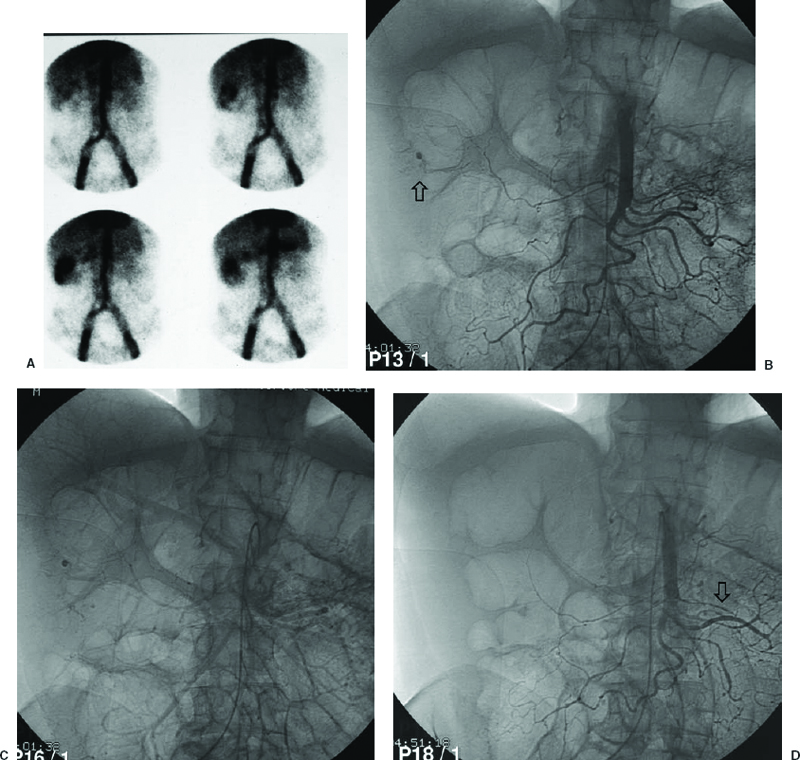

Diverticulosis bleeds more frequently in the right colon than in the left colon. Bleeding diverticula are often transient events and may not recur. Angiography shows contrast extravasation in the diverticulum and subsequently may show extravasation into the colonic lumen (Fig. 33-1).

FIGURE 33-1. Bleeding scan in a 71-year-old man with known diverticulosis. A: Acute hemorrhage is localized to the acending colon, just proximal to the hepatic flexure. B: Emergency selective superior mesenteric arteriogram demonstrates punctate extravasation on the arterial phase (arrow), persisting into the late venous phase. C, D: Follow-up arteriography after transcatheter vasopressin demonstrates cessation of hemorrhage. There is moderate focal spasm in a jejeunal branch related to the vasopressin (arrow).

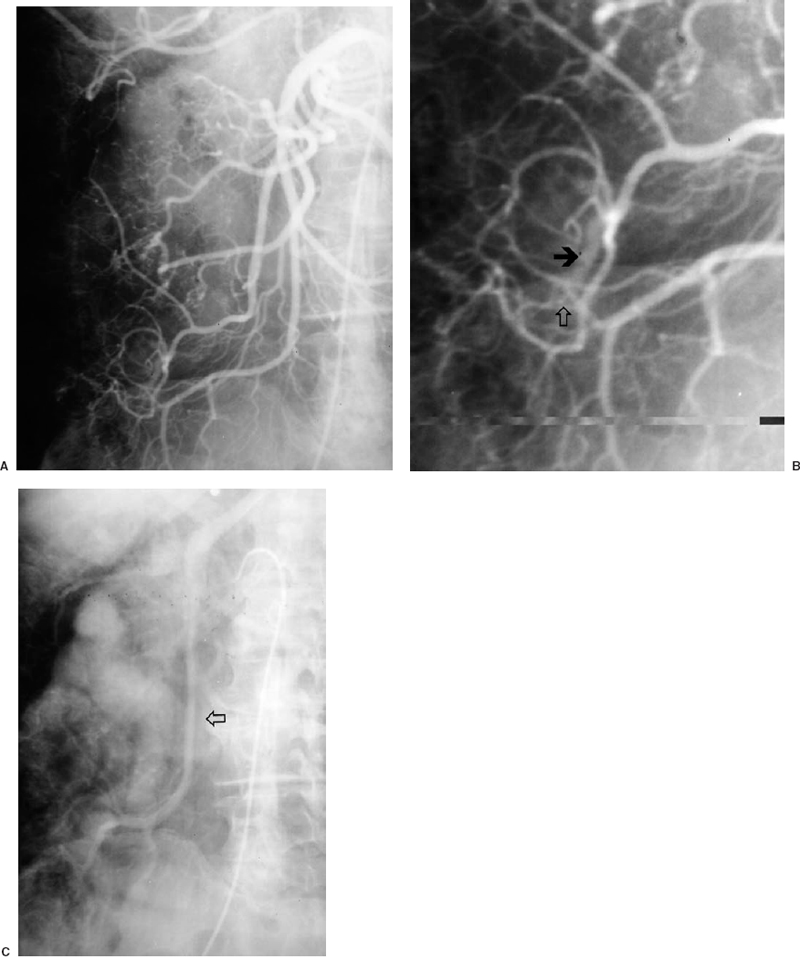

Arteriovenous malformations (angiodysplasia) of the large bowel usually occur in the cecum (cecal ectasia) and proximal ascending colon.7 Endoscopy is more sensitive than angiography for localizing angiodysplasia for chronic bleeding; infrequently, an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) can be seen with contrast extravasation during the course of an acute bleed. There may be an association with aortic valvular stenosis and with Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. Angiographically, the most important sign of angiodysplasia is an early draining vein, visualized before 6 sec on the superior mesenteric arteriogram (Fig. 33-2). Vascular tufting or the presence of an arterial blush and persistent and dense venous opacification are less specific signs. Because of the need to visualize native arteriovenous (AV) shunting, angiograms must be performed without vasodilator enhancement. Small bowel arteriovenous malformations may also be seen. In general, AVMs should be resected, because embolization is technically difficult and involves multiple feeders. Intraoperative localization of a small bowel lesion such as an AVM can be quite difficult. Resection can be expedited by advancing an angiographic catheter or guide-wire into the feeding artery for intraoperative palpation or injection of microcoils or methylene blue, which can be palpated or visualized on the serosal surface during laparotomy.8,9 AVMs can be multiple.

FIGURE 33-2. Angiodysplasia in proximal ascending colon in a 63-year-old woman with a history of multiple previous episodes of brisk lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A: There is simultaneous opacification of the ileocolic artery and vein during the arterial phase of the selective injection, consistent with an early draining vein and arteriovenous shunting. B: Magnification view better demonstrates the prominent, early draining vein (black arrow) as well as a subtle associated vascular tuft (white arrow), with increased tortuosity and caliber of the terminal ileocolic branch. C: Venous phase demonstrates marked prominence of the ileocolic vein (arrow).

Tumors usually present with indolent lower GI bleeding but occasionally bleed massively. Bleeding is more common in carcinomas of the left rather than right colon. There may be arterial encasement. Leiomyomas of the small bowel are usually hypervascular and present with a well-defined blush. AV shunting and early draining veins may be present (Fig. 33-3). These myomas can be differentiated from AV malformations by the circumscribed nature of the angiographic blush as well as the presence of mass effect. Angiography may be helpful for small bowel myomas because their extramucosal location may prevent visualization on a small bowel barium series. Arterial encasement may be seen with malignancies.

FIGURE 33-3. A 63-year-old woman with recurrent episodes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A: Hypervascular lesion in the jejeunum (arrowhead) with prominent draining vein (arrow). Because of the mass effect, this was thought to represent a tumor. B: Barium enema performed 1 week after angiogram demonstrates a submucosal mass (white arrow). At laparotomy, a schwannoma was resected.

Meckel’s diverticulum accounts for 1% of cases of GI bleeding and usually is seen in young patients (younger than 20 years of age), presenting as repeated episodes of brisk lower GI hemorrhage. In adults, it usually presents as slower, chronic GI bleeding. 99mTc pertechnetate abdominal scans can localize ectopic gastric mucosa and thus may be helpful in diagnosis. The scans are considered a sensitive technique for localization in children, but the sensitivity and specificity in adults are limited.10 Angiographic localization thus can play an important role. Meckel’s diverticulum is usually found in the terminal ileum, supplied by a persistent vitellointestinal artery (Fig. 33-4). Classically, this artery was described as an elongated artery without branching, having a group of tortuous vessels at its distal aspect and arising from the distal SMA. The vitellointestinal artery also may have a number of side branches along its entire length and exhibit no appreciable tortuosity. Demonstration of a Meckel’s diverticulum requires a high index of suspicion and may require the use of superselective catheterization.11,12

FIGURE 33-4. Meckel’s diverticulum. Vitellointestinal artery supplies the diverticulum (arrows).

Mesenteric Ischemia

Mesenteric Ischemia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree