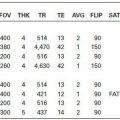

KEY FACTS

Congenital in nature, generally present in middle age (65% in patients >40 years of age).

Congenital in nature, generally present in middle age (65% in patients >40 years of age).

Very rare, incidence of 1:100,000 individuals. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) represent 25% of all intracranial vascular malformations.

Very rare, incidence of 1:100,000 individuals. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) represent 25% of all intracranial vascular malformations.

Symptoms: hemorrhage (usually parenchymal, 0.5% to 1% of these patients per year), seizures, and headaches. Increased chance of rupture during pregnancy.

Symptoms: hemorrhage (usually parenchymal, 0.5% to 1% of these patients per year), seizures, and headaches. Increased chance of rupture during pregnancy.

Risk of bleeding is 2% to 3% per year, and mortality is approximately 20% to 30% per bleeding episode. Cumulative risk of bleeding is 70%.

Risk of bleeding is 2% to 3% per year, and mortality is approximately 20% to 30% per bleeding episode. Cumulative risk of bleeding is 70%.

Factors associated with increased risk of bleeding: deep or periventricular location, intranidal aneurysm(s), venous aneurysms, and deep venous drainage.

Factors associated with increased risk of bleeding: deep or periventricular location, intranidal aneurysm(s), venous aneurysms, and deep venous drainage.

Location: more than 80% are supratentorial (especially parietal), over 80% are solitary, and 2% are multiple.

Location: more than 80% are supratentorial (especially parietal), over 80% are solitary, and 2% are multiple.

AVMs are solitary in 98% of patients, with multiple AVMs (2%) seen in Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome, Wyburn-Mason syndrome, craniofacial arteriovenous metamerie syndrome.

AVMs are solitary in 98% of patients, with multiple AVMs (2%) seen in Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome, Wyburn-Mason syndrome, craniofacial arteriovenous metamerie syndrome.

Major vascular supply is generally from internal carotid artery (ICA) (pial, 75%), but large AVMs may recruit external carotid artery (ECA) (durai, 15%) vessels or both (mixed, 10%) or even contralateral ICA and ECA.

Major vascular supply is generally from internal carotid artery (ICA) (pial, 75%), but large AVMs may recruit external carotid artery (ECA) (durai, 15%) vessels or both (mixed, 10%) or even contralateral ICA and ECA.

Computed tomography (CT) shows calcification in 30% of intracranial AVMs; cyst may be seen especially after stereotactic radiosurgery.

Computed tomography (CT) shows calcification in 30% of intracranial AVMs; cyst may be seen especially after stereotactic radiosurgery.

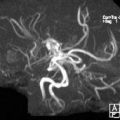

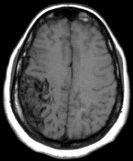

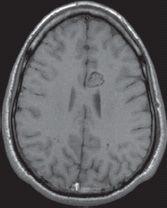

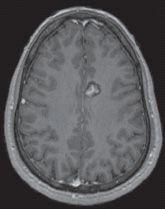

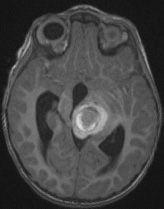

FIGURE 12-1. Noncontrast axial T1 shows a wedge-shaped AVM in the right frontoparieta region.

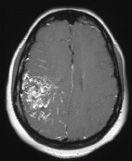

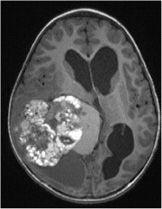

FIGURE 12-2. Corresponding postcontrast T1 shows enhancement of most of the lesion.

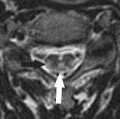

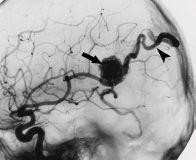

FIGURE 12-3. Lateral DSA view, in a different patient, shows AVM nidus (arrow) being fed by branches of the MCA and immediate filling of a draining vein (arrowhead).

FIGURE 12-4. Frontal TOF MRA view, in a different patient, only faintly shows AVM nidus (arrow) due to fast flow and signal dephasing.

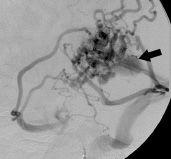

FIGURE 12-5. Frontal view of DSA in same patientas 12-4 shows feeding arteries, nidus, and draining vein (arrow) not seen on MRA due to fast and turbulent flow.

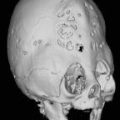

FIGURE 12-6. Three-dimensional DSA in a different patient shows a frontal AVM with multiple aneurysms (arrows) in feeding arteries. (See color insert)

FIGURE 12-7. Lateral DSA view, in a different patient, shows presence of AVM and an aneu-rysm (arrow) in draining vein.

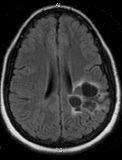

FIGURE 12-8. Axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) obtained 3 years after stereo-tactic radiosurgery shows no residual AVM but formation of cysts.

SUGGESTED READING

Gupta V Chugh M, Walia BS, Vaishya S, Jha AN. Use of CT angiography for anatomic localization of arteriovenous malformation nidal components. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1837–1840.

KEY FACTS

Slow-flow low-pressure malformations with no normal intervening brain parenchyma.

Slow-flow low-pressure malformations with no normal intervening brain parenchyma.

80% are supratentorial and 15% are multiple (often a familial component is present) and they may occur in the presence of developmental venous anomalies. Multiple (10% to 30%) ones maybe seen after irradiation or in a specific familial syndrome (autosomal dominant). Giant ones are more common in children.

80% are supratentorial and 15% are multiple (often a familial component is present) and they may occur in the presence of developmental venous anomalies. Multiple (10% to 30%) ones maybe seen after irradiation or in a specific familial syndrome (autosomal dominant). Giant ones are more common in children.

Second most common intracranial vascular malformation after developmental venous anomalies.

Second most common intracranial vascular malformation after developmental venous anomalies.

Annual risk of bleeding is <1%; when it occurs, it tends to be self-limited and clinically not significant; however, risk of bleeding increases after one hemorrhage. Hemorrhagic ones typically have a surrounding rim of moderate Tl hyperintensity.

Annual risk of bleeding is <1%; when it occurs, it tends to be self-limited and clinically not significant; however, risk of bleeding increases after one hemorrhage. Hemorrhagic ones typically have a surrounding rim of moderate Tl hyperintensity.

Most common clinical symptom is seizures (nearly 50%); most are asymptomatic.

Most common clinical symptom is seizures (nearly 50%); most are asymptomatic.

Many have associated venous malformations (called “transitional” type); cavernous malformations may form from occlusion of a vein in developmental venous anomaly.

Many have associated venous malformations (called “transitional” type); cavernous malformations may form from occlusion of a vein in developmental venous anomaly.

They are better visualized with T2* and SWI.

They are better visualized with T2* and SWI.

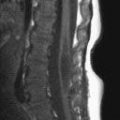

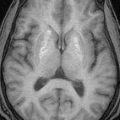

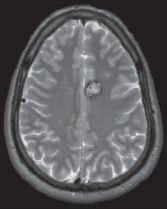

FIGURE 12-9. Axial noncontrast T1 shows typical “popcorn” or “mulberry” appearance of a cavernous malformation in the medial left frontal lobe.

FIGURE 12-10. Corresponding postcontrast T1 shows enhancement of the central part of the malformation.

FIGURE 12-11. Corresponding T2 shows a dark rim surrounding the lesion.

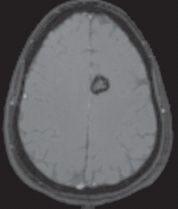

FIGURE 12-12. Corresponding T2* shows “blooming” of the rim due to magnetic susceptibility from chronic blood products.

FIGURE 12-13. Axial noncontrast CT, in a different patient, shows a dense left frontal cavernoma (arrow).

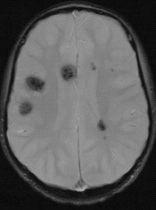

FIGURE 12-14. Axial T2*, in a different patient with familial cevernoma syndrome, shows multiple dark lesions.

FIGURE 12-15. Axial noncontrast T1, in a different patient, shows hemorrhagic cavernoma with typical hyperintense rim.

FIGURE 12-16. Axial noncontrast T1, in a different patient, shows a giant cavernoma.

SUGGESTED READING

de Souza JM, Domingues RC, Cruz LCH Jr, Domingues FS, Iasbeck T, Gasparetto EL. Susceptibility-weighted imaging for the evaluation of patients with familial cerebral cavernous malformations: a comparison with T2-weighted fast spin-echo and gradient-echo sequences. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:154–158.

Yun TJ, Na DG, Kwon BJ, Rho HG, Park S-H, SuhY-L, et al. A TI hyperintense perilesional signal aids in the differentiation of a cavernous angioma from other hemorrhagic masses. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:494–500.

DEVELOPMENTAL VENOUS ANOMALIES

DEVELOPMENTAL VENOUS ANOMALIES

KEY FACTS

Most common (60%) cerebral vascular malformation ( formerly called venous angioma).

Most common (60%) cerebral vascular malformation ( formerly called venous angioma).

Most are incidentally found and asymptomatic but occasionally may present with seizures, headaches, and/or focal neurologic deficits.

Most are incidentally found and asymptomatic but occasionally may present with seizures, headaches, and/or focal neurologic deficits.

Hemorrhage is uncommon but may occur with developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) located in the posterior fossa; when a venous malformation bleeds, a coexisting cavernous malformation (15% to 20%) is usually responsible for the hemorrhage. Hemorrhage may also be secondary to stenosis or thrombosis of a vein.

Hemorrhage is uncommon but may occur with developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) located in the posterior fossa; when a venous malformation bleeds, a coexisting cavernous malformation (15% to 20%) is usually responsible for the hemorrhage. Hemorrhage may also be secondary to stenosis or thrombosis of a vein.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree