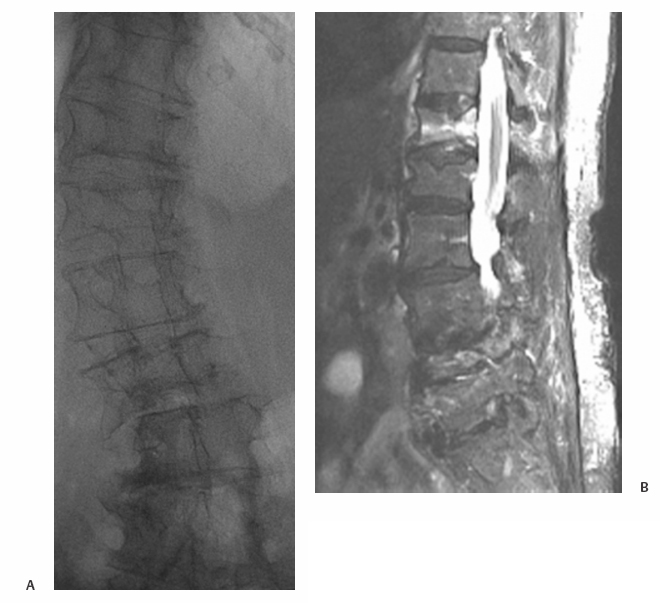

21 Vertebral Compression Fractures: Kyphoplasty Wayne J. Olan and Joey Marie Robinson Kyphoplasty is an established treatment for painful osteoporotic and pathologic compression fractures of the spine. First developed in the mid-1990s shortly after the development of vertebroplasty, and initially adopted by spine surgeons, kyphoplasty is now practiced increasingly by interventional radiologists. This procedure, like vertebroplasty, involves the percutaneous injection of bone cement into a fractured vertebral body. However, kyphoplasty also aims to reduce the fracture and restore endplate alignment and vertebral body height through the use of an inflatable bone tamp (balloon). The tamp is used to compress the cancellous bone to create a cavity and possibly realign the endplate of the vertebral body once the cavity is created. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is then injected into the cavity to stabilize the fracture. Safety, efficacy and positive results for pain relief have been reported widely in the literature throughout this decade.1–8 Vertebral compression fractures (VCF) caused by osteoporosis, tumors, malignancies, and other pathologies have a devastating impact on quality of life for patients. There is general consensus among physicians treating VCF patients that a significant reduction in quality of life and “downward spiral” of general health is associated with vertebral compression fractures. The pain associated with these fractures leads to loss of mobility and independence. For patients with osteoporosis, restricted movement further exacerbates the underlying disease, as less demand is placed on the skeletal structure and bone regeneration further decreases. Subsequent fractures of the spine as well as hip and other fractures are common among patients with untreated vertebral compression fractures.9 Most patients with a symptomatic VCF are treated with medical therapy, which includes bed rest, analgesics, and rehabilitation. Medical therapy is only partially effective at addressing symptoms with many patients having persistent pain and some degree of functional limitation.10 One of the potential results of a fracture in the thoracic and lumbar spine is kyphosis, which changes the patient’s center of gravity and puts the patient at greater risk of a fall. Kyphosis also limits the function of vital organs; restricted pulmonary function11–14 and compromised digestion due to kyphosis have long been documented anecdotally and are currently being studied. Clinically significant correction of the local deformity has been demonstrated throughout the literature in retrospective studies; however, at present, the clinical benefit of vertebral body fracture reduction on overall sagittal alignment is speculative.15 Clearly, further clinical studies regarding these issues would be of value to referring and treating physicians, as well as patients. Patient selection begins with a thorough history and physical examination; patients presenting with palpable, focal back pain should be referred for imaging. Plain film x-rays are often adequate to identify vertebral compression fractures. Further imaging studies, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and bone scan may be required to help the treating physician determine whether fracture reduction will be possible, which depends largely on the acuity of the fracture and density of the bone. Fractures treated within 4 to 6 weeks of the event have been shown to have greater restoration of vertebral body height and fracture reduction.16 The majority of acute osteoporotic and pathologic fractures from T7 to L5 can be treated safely. However, relative contraindications for kyphoplasty include vertebra plana or compression severe enough to prohibit insertion of the instruments. Exclusion criteria include asymptomatic VCFs; presence of osteomyelitis or systemic infection; retropulsed bone fragments; or epidural extension of tumor at the fractured level. Treatment of VCFs with retropulsed fragments or tumors intruding into the epidural space may result in cord compression during inflation of the balloon bone tamp. However, kyphoplasty is often considered a safer option than vertebroplasty for patients with degenerative VCFs of pathologic origin such as multiple myeloma. The cavity created by the balloon bone tamp may provide a more secure reservoir for the bone cement and may reduce risk of cement leakage in these specific cases (Fig. 21.1). Fig. 21.1 Imaging of T12 vertebral compression fracture (VCF) in a 90-year-old female patient. VCFs can often be identified in plain film x-rays or under fluoroscopy (a); magnetic resonance imaging (B) can better determine the acuity of the fracture and potential for fracture reduction and kyphosis correction through kyphoplasty. (Images courtesy of Orlando Ortiz, MD, MBA, FACR.) High-resolution biplane or C-arm fluoroscopy is essential to safe performance of percutaneous vertebral augmentation. Placement of instruments and injection of cement must be visualized in multiple planes throughout the procedure. Percutaneous vertebral augmentation requires informed consent of the patient prior to the procedure. Kyphoplasty is increasingly performed with the patient under conscious sedation, typically with an intravenous combination of Fentanyl (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) and Versed (Hoffman LaRoche, Nutley, NJ), rather than general anesthesia. This, however, is at the discretion of the operator and is typically addressed with the patient in advance of the procedure. Use of general anesthesia may include several factors, including the patient’s general health, comorbidities, and the ability of the patient to tolerate the prone position and remain still throughout the procedure. Many operators order the administration of conscious sedation prior to the patient being situated prone on the table. Kyphoplasty is performed under strict aseptic conditions; the operator and assisting staff follow sterile operating procedure. Because of the use of imaging equipment, care is also taken to protect the physician, staff, and patient through radiologic barriers including lead aprons, thyroid shields, and mobile barriers. Increasing use of lead barriers to absorb scatter radiation as well as pulsed fluoroscopy have demonstrated significant decrease in radiation exposure to the operator, staff, and patients.17

Background

Patient Selection

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree