- •

Heart disease remains the number one cause of death in women worldwide.

- •

Compared with men, women with symptoms consistent with IHD often present without obstructive CAD on coronary angiography and have a higher prevalence of persistent angina, nonobstructive CAD, CMD, SCAD, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, and HFpEF.

- •

Designed primarily for the identification of obstructive CAD, conventional diagnostic testing approaches for suspected IHD can lead to undertesting or overtesting in women without differentiating those truly at risk.

- •

Increasingly, nuclear cardiology and multimodality cardiovascular imaging tools are being applied to better diagnose pathologic phenotypes prevalent in women, including ischemia with no obstructive CAD and CMD and to aid in the development of needed evidence-based strategies for their management.

Introduction

Diagnostic testing approaches for the evaluation of heart disease in women have historically paralleled those in men. Based on an assumption that stable ischemic heart disease (IHD) in women was the same as that in men except occurring about a decade later, conventional efforts focused on identification of obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD) as the principal etiology for symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea, common in both women and men. We now recognize that several unique factors related to the presentation, diagnosis, and underlying pathophysiology of IHD in women necessitate a more tailored, evidence-based approach to their assessment of risk, complete with guidelines for sex-specific management strategies when appropriate. , Still, because most recommendations were derived predominantly from studies performed in men, the diagnostic utility and accuracy of testing in women can be undermined by lower predicted and observed probabilities of finding obstructive CAD. Currently, little high-quality data exist regarding optimal diagnostic strategies for the assessment of symptomatic women to establish or exclude a diagnosis of IHD.

Sex differences in ischemic heart disease

Epidemiology and risk factors

Despite this, heart disease remains the number one cause of death in women worldwide, and important sex differences in the rates of diagnosis, utilization of care, response to therapy, and clinical outcomes have been described. , Although these partly reflect that women outnumber men in the older populations at greatest risk for heart disease, women also often present with a higher burden of comorbidities and experience worse outcomes compared with men. Women relative to men have a higher prevalence of persistent angina, nonobstructive CAD, coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), stress-induced cardiomyopathy, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus (DM) and atrial fibrillation, are associated with higher rates of vascular complications in women versus men, and women account for a disproportionate burden of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, which have also been linked to increased cardiovascular morbidity. Women presenting with acute coronary syndromes experience higher mortality compared with men, , with lower utilization of cardiac device therapy, despite data showing increased benefit, and are referred for cardiac transplantation at later stages of heart failure.

As a result of a greater symptom burden and rate of functional disability in women, together with a lower prevalence of obstructive CAD by coronary angiography, the evaluation of IHD in women compared with men can present unique challenges to clinicians. The accuracy of standard noninvasive diagnostic testing for ischemia, such as stress testing with exercise electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, or semiquantitative nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), can vary significantly when evaluated against a gold standard of identifying anatomic obstructive CAD. This is especially important for women, whose symptoms are less likely to be explained by findings on coronary angiography in both acute and chronic presentations of disease and whose abnormal stress tests in the absence of obstructive CAD are more likely to be interpreted as false-positives. , Nevertheless, women with angina and confirmed ischemia or myocardial infarction (MI) have increased mortality from heart disease. This chapter highlights how the recent clinical application of novel diagnostic tools in nuclear cardiology and multimodality cardiovascular imaging is leading to a paradigm change in how heart disease is diagnosed, , broadening the definitions of CAD and ischemia, respectively, to better reflect the pathologic phenotypes more prevalent in women.

Moving beyond obstructive coronary artery disease

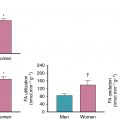

Obstructive CAD, defined anatomically on coronary angiography as luminal narrowing of 70% or greater in the major epicardial arteries (or 50% or greater in the left main artery), is neither necessary nor sufficient to explain symptoms of IHD. Indeed, women present more frequently than men with symptoms of angina , ( Fig. 16.1 ) but are less likely to have anatomic obstructive CAD. In a contemporary cohort of 11,223 symptomatic patients (42% women) referred for nonurgent coronary angiography, one-third of men and two-thirds of women had no obstructive CAD, and these patients still experienced an elevated risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). Among patients with stable angina who are found to have obstructive CAD, sex differences also exist in the extent and severity of disease, with women less likely than men to have obstructive multivessel disease. Sex differences in angiographic findings have been demonstrated not only in IHD but also in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes, including unstable angina and MI. In autopsy evaluations of patients who died of ischemic heart disease, women demonstrated less extensive and less obstructive CAD than men, despite pathologic evidence of MI, with more evidence of plaque erosion than plaque rupture. Despite consistently documented lower angiographic disease burden and more often preserved left ventricular (LV) function compared with men, women with IHD have similar adverse outcomes ( Fig. 16.2 ). ,

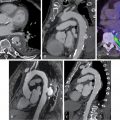

This paradox may be at least partly explained by the finding that a visually normal coronary angiogram does not necessarily indicate a normal coronary circulation ( Fig. 16.3 ). Beyond obstructive CAD, vascular dysfunction in the form of abnormal coronary reactivity often coexists with diffuse, nonobstructive atherosclerotic plaques and CMD. , , , Although invasive coronary angiography using visual assessments of epicardial coronary luminal patency remains a cornerstone of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, it has limited ability to identify diffuse atherosclerosis and small-vessel dysfunction. The addition of invasive fractional flow reserve, an assessment of the pressure drop across a focal epicardial stenosis, to coronary angiography has proven beneficial to identify lesion-specific ischemia and guide revascularization but may still underestimate the integrated contribution of diffuse atherosclerosis and small-vessel disease on myocardial ischemia. , Nonobstructive CAD and CMD have been implicated in adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including acute coronary syndromes, heart failure, and death from plaque erosion and impaired vasoreactivity with ensuing myocardial ischemia. , As a result, testing for IHD, especially in women, is now moving beyond testing for the presence or absence of obstructive epicardial CAD, which represents one of several possible contributors to myocardial ischemia. Over the last decade, the clinical integration of advanced diagnostic imaging tools is helping to redefine IHD and highlight the importance of nonobstructive CAD and CMD. Specifically, noninvasive approaches using coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), positron emission tomography (PET), and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging have provided very sensitive assessments for the evaluation of anatomic atherosclerotic plaque, functional ischemia, and myocardial fibrosis, respectively.

Patient-centered clinical applications of imaging in women

Case vignette 1: Noncardiac chest pain

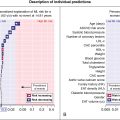

A 60-year-old female with a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia and a family history of premature CAD was referred for a vasodilator stress myocardial perfusion PET/computed tomography (CT) study to evaluate subacute chest pain. Her mother had experienced a heart attack at age 50, resulting in urgent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The patient’s symptoms had begun 2 weeks before while she was doing vigorous housework after dinner and included epigastric and substernal chest burning in association with lightheadedness and mild difficulty breathing, prompting evaluation at her local hospital emergency room. There, she was found to be hypertensive with a blood pressure of 164/84 mm Hg, with a normal resting ECG. Symptoms improved with rest and administration of sublingual nitroglycerin. She was ruled out for acute MI with serial negative cardiac troponins. A stress test was recommended before discharge, but the patient declined to stay overnight. Her cardiologist referred her for a cardiac PET/CT study during outpatient follow-up. Myocardial perfusion images were normal (demonstrating a basal lateral 13 N-ammonia PET artifact), and there was no evidence of ischemia or scarring, with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 66% and no regional wall motion abnormalities. Quantitative assessment of regional and global myocardial blood flow (MBF) demonstrated a robust global peak stress value of 2.08 mL/min/g and global myocardial flow reserve (MFR) of 3.27 with no regional variation (including along the segment of visual perfusion artifact) ( Fig. 16.4 ). Gated cardiac CT images demonstrated no coronary artery calcification, with an Agatston coronary calcium score of 0. They also demonstrated evidence of a small hiatal hernia.

In summary, this symptomatic patient with cardiac risk factors and a family history of premature CAD was found to have noncardiac chest pain, likely related to gastroesophageal reflux and spasm. In this case, stress testing with cardiac PET-CT provided a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, confirming no evidence of flow-limiting CAD or CMD, normal global LV systolic function, and no coronary artery calcium while also providing supporting evidence for a noncardiac etiology of her chest pain, reassuring the patient and her health care providers of an excellent cardiac prognosis and minimizing the need for downstream testing and procedures.

Emerging role of coronary computed tomography angiography

In addition to the use of noncontrast cardiac CT to define the burden of calcified plaque, the use of noninvasive CCTA has dramatically increased test sensitivity for the diagnosis of CAD and also enabled early characterization of plaque morphology. CCTA could have been used as an alternative approach to diagnosis in Case Vignette 1. Indeed, of available diagnostic testing strategies, a normal CCTA has one of the highest negative predictive values for excluding significant CAD. Recent observational studies have revealed stepwise incremental risk for future adverse events in patients along a continuum of both severity (i.e., mild, moderate, or severe stenosis) and extent (i.e., number of involved segments or vessels) of atherosclerotic plaque. , Accelerated by the growth of CCTA, mounting evidence now supports that (1) the presence of any atherosclerotic plaque, obstructive or not, portends an increased risk for events, and (2) the higher the overall plaque burden that is present, the higher the risk. From the international multicenter COroNary CT Angiography Evaluation For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter Registry (CONFIRM) registry, in which 23,854 consecutive patients without known CAD (33% asymptomatic) underwent CCTA between 2005 and 2009, per-patient nonobstructive and obstructive CAD conferred an increased risk for mortality in a stepwise manner compared with absence of CAD, which was associated with very low risk. In a subsequent sex-specific subgroup analysis of patients with no or nonobstructive CAD (n = 18,158), nonobstructive CAD was associated with a modest adjusted risk of MACEs (composite of death and nonfatal MI) that was similarly increased in both women and men. Also, in a smaller subset of patients with longer follow-up (n = 5632 followed for 5 years, 30% with nonobstructive CAD), there was no interaction of sex on the association between per-vessel extent of obstructive CAD and MACE, and authors concluded that exploratory analyses of atherosclerotic burden did not identify sex-specific patterns predictive of MACE. Thus, women and men with comparable risk and extent of CAD had a comparable prognosis. Nonetheless, prevalent patterns of disease do differ between women and men, with more symptomatic women than men manifesting nonobstructive rather than obstructive CAD, , , with important implications for diagnosis and management.

Among nonobstructive plaques, CCTA also allows for characterization of high-risk plaque features, including positive remodeling, low CT attenuation plaque, spotty calcification, or napkin-ring sign consisting of ring-like peripheral higher CT attenuation with central low attenuation. In an observational substudy of the Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) trial including 4415 symptomatic outpatients (52% women) who underwent CCTA and were followed for a median of 25 months for a composite of MACEs (death, MI, and hospitalization for unstable angina), the presence of high-risk plaque in patients with nonobstructive CAD increased the adjusted risk for adverse events by 1.6-fold, and high-risk plaque was more strongly associated with events in women (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.41; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25 to 4.64) than in men (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.81 to 2.39). Nonetheless, the positive predictive value for future MACEs of high-risk plaque detection in these patients was low (only 4.8% of patients with high-risk plaque experienced aMACE), limiting its current clinical applicability.

Case vignette 2: Coronary artery disease without ischemia

A 74-year-old asymptomatic female with a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia was referred for a coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan for cardiovascular risk assessment. Two years prior, she had undergone an exercise stress test for evaluation of dyspnea. At that time, she exercised for 10 minutes on a Bruce treadmill protocol, achieving 11.7 METs with normal heart rate and blood pressure response, stopping for dyspnea. Her ECG response to exercise demonstrated 1- to 2-mm horizontal ST-segment depression in leads II, III, aVF, and V4 to V6, beginning 5 minutes and 31 seconds into the test and resolving 7 minutes into recovery. She subsequently underwent repeat exercise testing with 99m Tc SPECT MPI. Stress ECG findings were unchanged, and her MPIs were normal, with LVEF 68% and normal regional wall motion and thickening.

Her noncontrast CT demonstrated severe multivessel coronary calcifications involving primarily the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, as well as the left circumflex (LCx) coronary artery and right coronary artery (RCA), with an overall Agatston score of 793. This score placed her in the 93rd percentile of individuals for her age, gender, and race.

She was then referred for evaluation with 13 N-ammonia cardiac PET/CT. The ECG response to vasodilator stress with regadenoson again demonstrated diffuse 1-mm horizontal ST-segment depression, and the limited CT transmission scan for attenuation correction also demonstrated severe coronary calcifications. MPI was normal with no evidence of regional flow-limiting CAD. Furthermore, quantitative stress MBF and flow reserve values were globally preserved at 2.21 mL/min/g and 2.29, respectively, with no regional variation ( Fig. 16.5 ).

In summary, this elderly asymptomatic patient with multiple cardiac risk factors, perhaps unsurprisingly, has a high burden of coronary atherosclerosis. Reassuringly, she also demonstrated a high capacity for exercise and normal cardiac PET results with no ischemic sequelae of her anatomic disease. Despite the extent and severity of her coronary calcifications, she demonstrated normal regional and global stress MBF and MFR, with no evidence of CMD. As such, even though her positive stress ECG findings likely represented false-positive results, her normal SPECT MPI was not “falsely negative,” as confirmed by more sensitive PET testing. These results corroborate her lack of ischemic symptoms at a high exercise workload and normal LVEF on both SPECT and PET. Although she is at high risk for future ischemic heart disease events given her burden of atherosclerosis, there is no indication for invasive angiography or revascularization at this time. She was continued on preventive therapy with low-dose aspirin, high-intensity atorvastatin, and antihypertensive medications.

Case vignette 3: Ischemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease

An 86-year-old female with a history of DM, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, atrial fibrillation, sinus node dysfunction requiring pacemaker placement, HFpEF, and mild coronary calcifications was referred for a vasodilator stress myocardial perfusion PET/CT study to evaluate dyspnea, which had begun 4 weeks prior. A transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed LVEF of 50% to 55% with no regional wall motion abnormality, moderate biatrial enlargement, and diastolic dysfunction. Cardiac PET/CT demonstrated normal regional myocardial perfusion on both stress and rest images, with an LVEF of 54% and no regional wall motion abnormalities. Nevertheless, quantitative stress MBF was severely reduced at 1.10 mL/min/g with minimal regional variation, with an abnormal global flow reserve of 1.63 ( Fig. 16.6 ). Given concern for diffuse high-grade CAD, the patient underwent invasive coronary angiography, which demonstrated a long proximal LAD stenosis of 60%, with minimal atherosclerotic plaque involving the LCx and RCA. Instantaneous wave-free ratio of the LAD was 0.91, confirming absence of flow-limiting disease.

In summary, this patient with multiple cardiac comorbidities and HFpEF has CMD and ischemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA). As in her counterpart with obstructive CAD, this patient requires aggressive medical therapy and risk factor reduction, including optimal management of blood pressure, lipids, weight, and glycemia. Efforts are ongoing to more precisely phenotype patients like this one who have nonobstructive CAD and CMD, many of whom are women, to determine which additional interventions may be effective. Newer therapies targeting residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk, neurohormonal activation and glucose handling in the kidneys, and even surgical weight loss may demonstrate improved outcomes in these patients. This case illustrates how defining CAD not only as an anatomic problem but also a functional one (for which modern tools may be leveraged in future clinical trials to interrogate the full extent of the coronary circulation) may lead to a more complete understanding of the pathobiology of IHD, with the goal of improving outcomes for all patients.

Emerging role of positron emission tomography

Neither conventional angiography nor CCTA can detect CMD, which is defined not anatomically but functionally as a reduced MFR in the absence of flow-limiting CAD, as illustrated in Case Vignette 3. As discussed in Chapter 13 , regional and global MFR, calculated as the ratio of hyperemic to rest absolute MBF averaged over the left ventricle, is an integrated marker of coronary vasomotor dysfunction that measures the hemodynamic effects of focal, diffuse, and small-vessel CAD on myocardial tissue perfusion , and has emerged as an important prognostic imaging marker of cardiovascular risk. Observational data have shown that MFR measurements using cardiac PET distinguish patients at low or high risk for MACE, including cardiac death, beyond comprehensive clinical assessment, myocardial perfusion defects, LVEF, low-level troponin elevation, diastolic dysfunction, or plaque severity on invasive coronary angiography. In parallel to findings with atherosclerotic plaque, evidence now supports that (1) the existence of impaired MFR, whether in the presence or absence of obstructive CAD, portends increased risk for cardiovascular events and (2) the more severely impaired the overall global CFR, the higher the risk. Although an MFR greater than or equal to 2 effectively excluded high-risk angiographic CAD and was associated with low rates of annualized cardiac death, event rates for patients with MFR less than 2 increased exponentially as MFR decreased. , Because MFR is a measure of not only the effects of epicardial obstructive CAD, but also of diffuse atherosclerosis and CMD on myocardial tissue perfusion, worse prognosis in patients with an MFR of less than 2 may be related to coronary vasomotor dysfunction arising from a mix of pathophysiologic CAD phenotypes. As such, it may be particularly useful for diagnosis and prognosis of symptomatic women with suspected stable IHD.

Indeed, CMD often coexists with diffuse, nonobstructive atherosclerosis. , , Similar to CCTA findings for nonobstructive CAD, cardiac PET studies support that CMD is prevalent in symptomatic patients, affecting approximately 50% of patients who were found to have normal MPI and LVEF after referral for noninvasive evaluation ( Fig. 16.7 ). When present, CMD was associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of sex but was more common in women, who accounted for two-thirds of these patients. Although most patients had some atherosclerotic plaque, results were consistent even in patients with a CAC score of 0, and global MFR, but not CAC, provided significant incremental risk stratification over clinical risk score for prediction of MACEs. Thus, symptomatic patients who do not demonstrate regional ischemia associated with flow-limiting CAD may have diffuse atherosclerosis and CMD for which a more sensitive, quantitative assessment of ischemia may better diagnose abnormalities and identify novel targets for systemic therapies. Although not a uniquely female disorder, this pattern of abnormalities may be more prognostically useful in women because they often occur absent obstructive CAD. In women, smaller epicardial coronary arteries coupled with differences in shear stress and inflammatory mediators over the lifespan may modify the development of CAD into a diffuse pattern with more contribution from CMD than focal obstruction. Such an effect would be consistent with previously described clinical and pathologic observations of sex differences in the presentation of IHD.